It is hard not to be captivated by Nigeria.

I have been looking at a lot of global economic and demographic charts lately, and Nigeria’s data is just sexy: a massive market of 230 million people—one in every six Africans is Nigerian. A labor dividend with a median age of just 18. Once the largest economy on the continent. In my mind, this was supposed to be the African success story—a nation that moved past warlord chaos to leverage its oil wealth for an industrial takeoff, a rising Wakanda.

With expectations of finding the world’s next growth engine, I started digging into the underlying logic of the country. But as I peeled back the macro data, what lay before me wasn’t an organically growing modern state, but a high-entropy mess that defies standard economic theory.

To truly understand this place, you have to drop your preconceptions of what a “nation-state” is and accept a cold reality: Nigeria is not a natural community; it is a forced business contract.

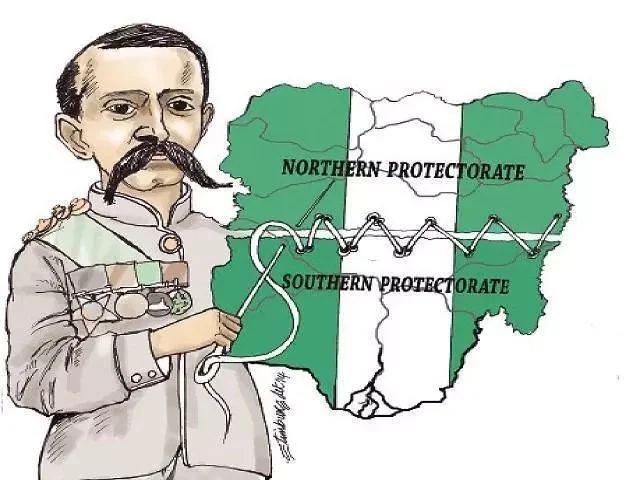

1. 1914 A Family Merged to Balance the Books

The story doesn’t start on the African savanna, but at a desk in 1914 occupied by British colonial officer Lord Lugard. He faced a sticky accounting problem: the vast Northern Protectorate was bleeding money, while the Southern Protectorate was flush with cash from liquor imports and trade taxes.

To save the British taxpayer from covering the North’s deficit, Lugard made a bold stroke and merged the two. He didn’t create a fusion of civilizations; he simply balanced a ledger.

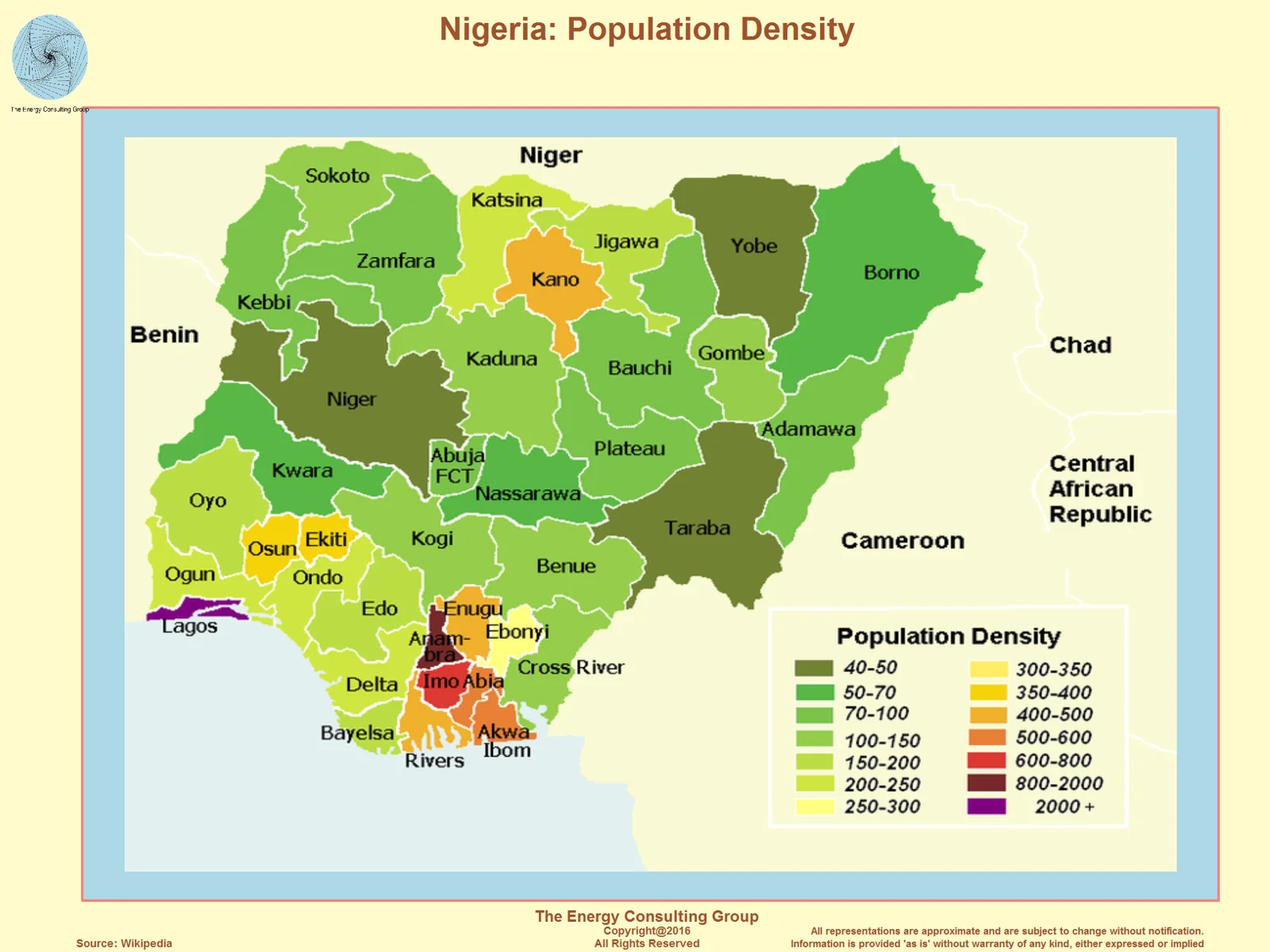

Nigeria was born as a geopolitical vessel for transfer payments. This determined its destiny for the next century: the Hausa-Fulani North provided the bodies and the votes (maintaining a feudal structure), while the Yoruba and Igbo South provided the money and tech (maintaining a commercial structure). The two sides have been locked in a tense duality ever since—mutually resentful, yet forced into symbiosis.

2. Oil The Accidental Bind

This symbiotic relationship flipped on its head in the 1960s, driven by the substance that would come to dominate the nation’s fate: oil.

Before oil, the Southern Igbos were the staunchest supporters of unity, eager to access the massive Northern market. The North, fearing domination by the more educated Southerners, was the side threatening to secede. But when oil gushed from the swamps of the Southeast, the script flipped instantly. The Igbos tried to break away and form the Republic of Biafra to keep the oil wealth, while the North—terrified of losing their subsidies—became the fiercest defenders of “One Nigeria.”

The resulting civil war ended in Southern defeat, but it cemented the country’s core operating principle: the oil pipeline is the glue preventing dissolution. A steel cable of shared interests anchors together a nation that geography and culture try to tear apart.

3. All Cash No Governance

This logic shaped Nigeria’s unique political economy—a pure patronage system.

Politics isn’t about public service; it’s about the distribution of oil rents. Every month, elites fly to the capital, Abuja, to slice up the oil revenue, which then trickles down to tribal bases. This mechanism shrewdly converts potential class conflict into ethnic rivalry. The poor don’t hate the corrupt big men of their own tribe; they fear that if their “Big Man” falls, the tribe’s lifeline gets cut.

Economically, a massive paradox confuses observers: in a country where oil is 90% of export earnings, why is there almost no sign of oil wealth on the streets?

The data reveals the truth: oil controls the nation’s vitals but makes up only 9% of GDP. Nigeria is a dual economy, like a disembodied beast. The government lives in the clouds on oil dollars, unaccountable to taxpayers, while the people live in the dust, hustling to survive. The state and the people inhabit parallel economic universes.

4. The Wolves of Commerce

In this vacuum of governance, Nigerians were forced to evolve. No electricity? Buy a generator. No police? Hire security. The harsh environment forces every individual to become a micro-government. This pressure cooker forged a ruthless commercial adaptability, especially among the Igbos.

With the petro-economy driving up exchange rates and inflation, imported food became cheaper than local produce. Farming became a slow death; business was the only jailbreak. The people fled production for circulation. The Igbos, much like the Wenzhou merchants of China, perfected a unique apprenticeship system. It is a grassroots VC model: seven years of unpaid labor in exchange for startup capital. It solved the lack of bank loans and liquefied the population into flowing commercial capital.

In Lagos’s Computer Village, you feel the visceral power of this vitality. It is the perfect counterpart to Shenzhen’s Huaqiangbei. If Huaqiangbei is the heart of global hardware—creating and ordering (entropy reduction)—Computer Village is the stomach, digesting and resurrecting (entropy increase). In that maze of tin shacks, any e-waste can be given another three years of life. Chinese companies like Transsion won this market precisely because they understood these pain points: the lack of power, the noise, and the specific needs of darker skin tones.

5. Dominance Through Noise

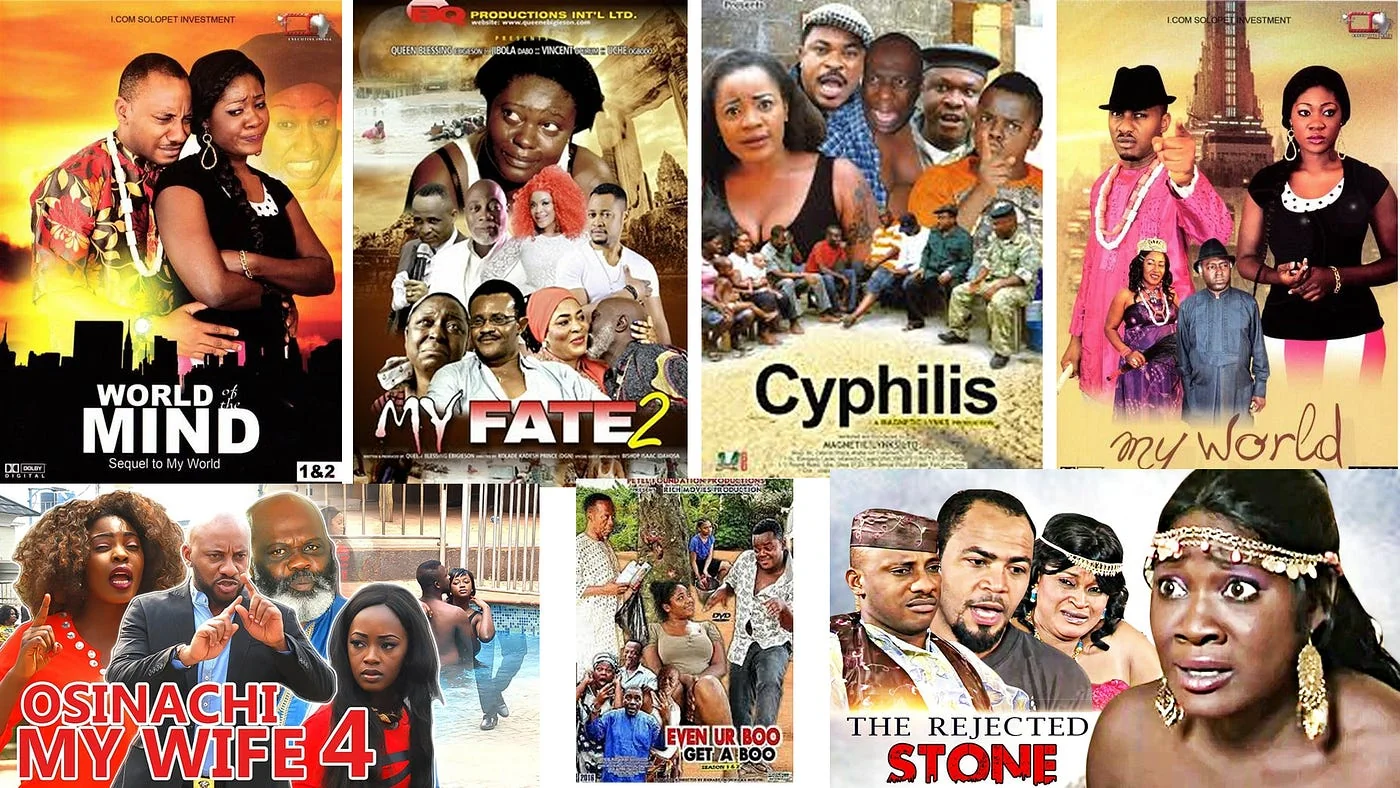

This high-pressure environment accidentally forged a cultural superpower. In the deafening markets of Lagos, only the signal with the highest signal-to-noise ratio—the loudest, most confident, most aggressive—gets heard. Projected onto culture, this survival strategy became Afrobeats and Nollywood.

Other continents might not feel it yet, but within Africa, Nigeria is the undisputed cultural hegemon. Their movies tell the stories of ordinary African hustle, ruling screens from Kenya to South Africa; their music defines the rhythm of modern Africa. This wasn’t a state strategy; it was the sublimation of suffering.

Yet, beneath this commercial boom and cultural swagger, there is little national identity. Nigerians are like strangers trapped in a malfunctioning elevator. They may mistrust or even despise each other, but they bond over the shared misery of the elevator.

If anything truly binds them, it’s not a shared ideal, but shared trauma. Pidgin English has become the only adhesive for these strangers, recording their collective memory of survival inside the belly of this dysfunctional beast.

6. Outsourcing Tax to Gangs

As state capacity rots further, the power vacuum is being filled by something else.

On the streets of Lagos, uniformed thugs from transport unions—Agberos—openly tax drivers. This isn’t just crime; it’s outsourced governance. The government tacitly allows gangs to maintain minimal order and collect protection fees in exchange for a cut. As economist Mancur Olson described with “Stationary Bandits,” the gangs have become the de facto rulers. Data suggests these gangs in Lagos collect more revenue than the official tax receipts of many other states.

This is a profound governance crisis. In the short term, gang rule creates a facade of order. But in the long term, without the rule of law, heavy industry cannot survive, and the educated class will continue to flee.

The Nigerian behemoth faces two closing walls: the global energy transition and a population explosion that is breaching the physical limits of extraction. When the day comes that the steel cable snaps, the real test begins.