Friction, as taught in high school, is a simplified concept. It glosses over several underlying physical phenomena.

High school physics dictates that friction depends solely on surface roughness and the normal force. Contact area supposedly doesn’t matter.

While true in specific scenarios, this oversimplification obscures friction’s real mechanism. In reality, there’s no horizontal resistance along the contact surface. Perfectly smooth, ideal objects would experience zero friction, proving this.

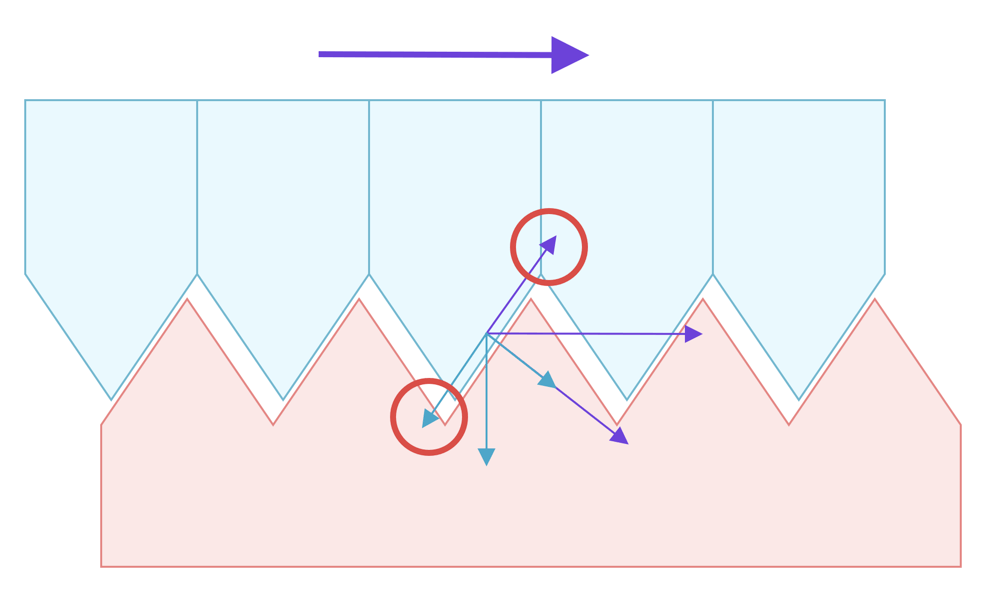

Movement is actually hindered by the minuscule upward force required to lift one object over the other’s microscopic imperfections. Real-world surfaces are jagged. Two objects interlock, akin to gears (though less rigidly). Imagine the contact surface as a multitude of tiny, identical ramps. The top object rests on these ramps like a series of tiny toothpicks, similar to letterpress printing.

Moving the top object requires pushing each “toothpick” up its ramp. Once elevated, it clears the ramp’s peak. This necessitates overcoming the toothpick’s weight. Gravity and the pulling force can both be decomposed into components parallel and perpendicular to the ramp. The perpendicular components create equal and opposite reaction forces, which are irrelevant here. Only when the upward pull exceeds gravity’s downward component does movement begin. This is the essence of friction.

Therefore, friction isn’t truly independent of contact area. A larger area implies more ramps, increasing the overall normal force (N). High school physics, however, claims that changing an object’s orientation (standing vs. lying) doesn’t alter friction. This is because, while N increases, each “toothpick” shortens, reducing its weight and the downward gravitational component along the ramp. The force to move each toothpick decreases proportionally. These effects mathematically cancel out, maintaining constant friction.

However, concluding that friction is area-independent is misleading. Everyday experience confirms that larger areas do exhibit greater friction.

Two articles shed light on the true nature of friction: https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/22165913 https://www.guokr.com/article/459070

Many believe fingerprints enhance grip by increasing friction. While the outcome is correct, the reasoning is flawed. Fingerprint grooves actually reduce contact area. Theoretically, a smooth finger would have a stronger grip under equal pressure. So, why fingerprints?

Fingers employ another tactic: sweat. Sweat softens the skin’s keratin, improving conformity, like interlocking gears. This creates more tiny ramps within the same area.

Excessive sweat, however, reduces friction. Wet hands struggle to open jars. An optimal moisture level exists; too much is counterproductive. Fingerprint grooves help regulate this by draining excess sweat.

Friction is ubiquitous. We spent six years in high school, solving countless problems involving blocks on various surfaces. Yet, not a single problem delved into friction’s underlying mechanism.