Spring had just arrived in Dunhuang in early April, a couple of months before peak season. Despite the Qingming Festival holiday, it wasn’t crowded. Some sights, like desert plants or the Populus euphratica forest, weren’t yet in bloom.

Day 1: Departure and Dunhuang Museum

We flew from Hangzhou, connecting in Lanzhou before heading to Dunhuang. The landscape changed dramatically as we approached – a stark contrast to the south.

Dense, snow-capped mountains appeared below the clouds – the Qilian Mountains. Lower down, melted snow revealed dark rock. The terrain flattened into a dark brown Gobi desert, the boundary between the two strikingly clear. Further on, wind and temperature shaped the land into vast yellow sands. Finally, Dunhuang, a desert city, emerged through the clouds. The whole scene felt like an amazing 4D movie or game cutscene.

I’d hoped to avoid sandstorms, but the airport wind was fierce. The kind that makes you chase your hat, only to get a mouthful of sand.

One gust, a mouthful of sand, and you’re ready for adventure?

Luckily, we’d rented a car. We picked it up and went straight to the hotel. After dropping our bags, we visited the Dunhuang Museum. (Museum = geography and history lesson. Skip ahead for pictures if you prefer.)

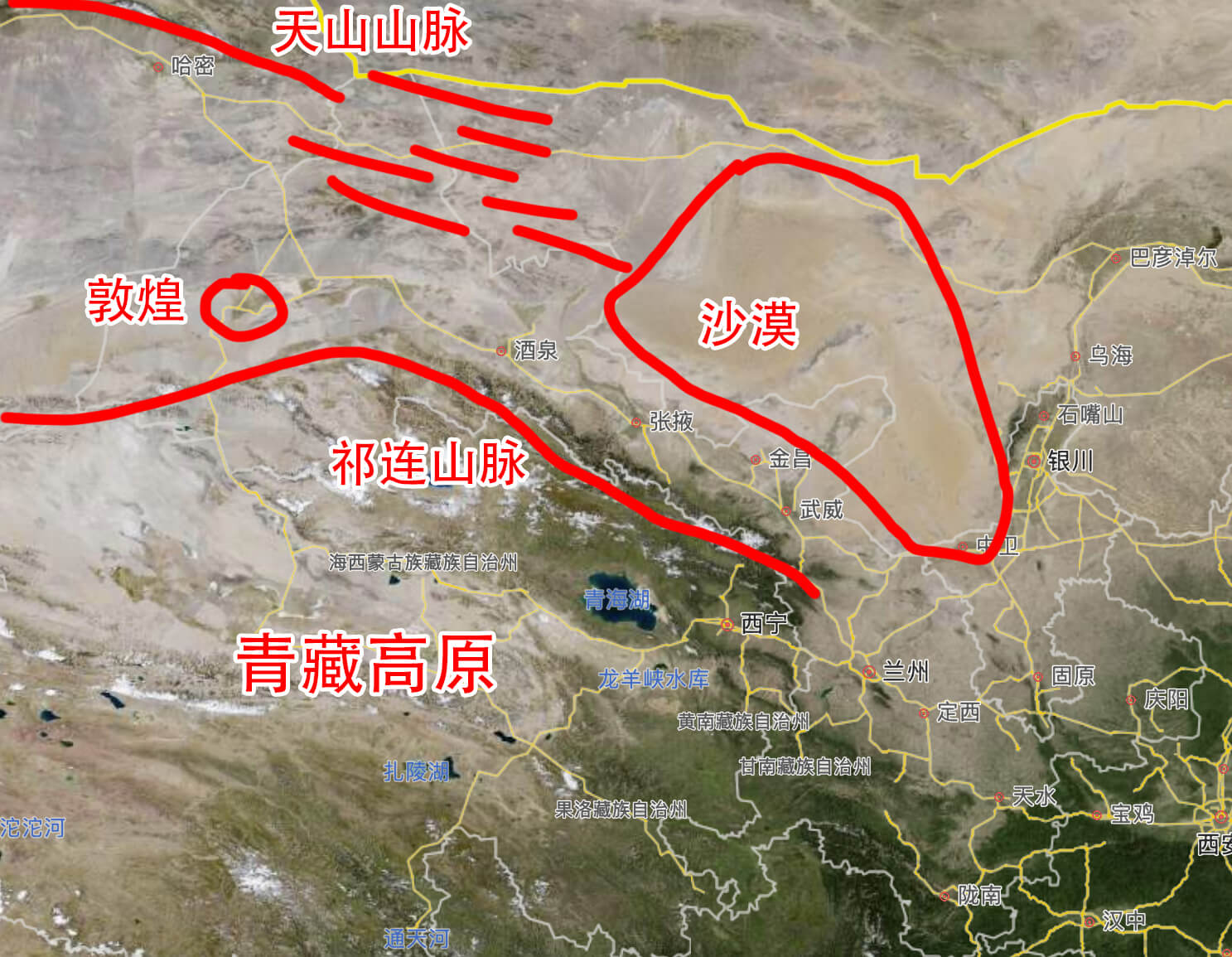

Geography

Dunhuang, a county-level city under Jiuquan, is Gansu’s westernmost city. It’s closer to Hami in Xinjiang than Jiuquan, acting as a key passage to Xinjiang.

Dunhuang is inseparable from the Hexi Corridor. It forms a line with Jiuquan, Zhangye, Jinchang, and Wuwei to its east, connected by a single highway. Gansu’s map looks like a bone: the larger southeastern part is Gannan (centered on Lanzhou), while the middle and northwest are roughly the Hexi Corridor.

The Hexi Corridor’s geography is unique – a narrow passage with obstacles on either side. The Qilian Mountains lie to the south, with the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau beyond. The desert of western Inner Mongolia is to the northeast. Mountains from the Tianshan range are to the north. The corridor connects to Gannan and central China in the southeast, and to Xinjiang (the ancient Western Regions) in the other direction.

The Hexi Corridor is the Silk Road’s throat; Dunhuang is its gateway.

History

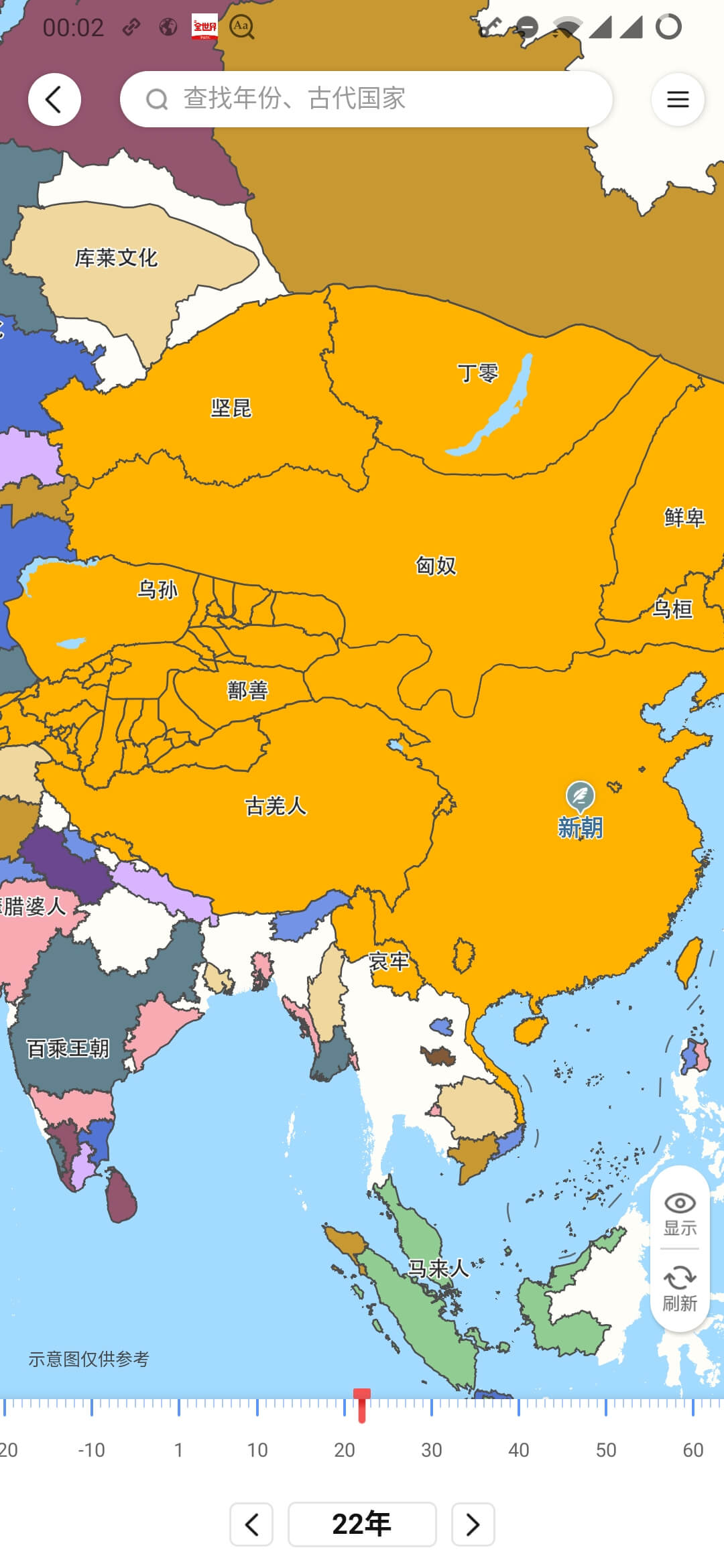

Most Chinese dynastic conflicts were within the Great Wall. It separated northern nomads, while the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau isolated plateau peoples and Central Asian civilizations. The Shu region blocked South Asian forces. Imagine ancient Han Chinese territory as a water bag with one opening: facing northwest, towards Dunhuang. This location gave Dunhuang an extraordinary historical role.

Civilization thrives on exchange, not just resources. Contact with the Western Regions began in the Western Han Dynasty. Zhang Qian’s mission, despite two captures by the Xiongnu, established relations and connected the Silk Road. The Han Dynasty controlled the Hexi Corridor, with Dunhuang at the forefront of cultural exchange. At its peak, the Protectorate of the Western Regions directly administered the area. The Han Great Wall and Yumenguan’s beacon towers witnessed this.

Silk Road trade wasn’t just China and the Western Regions. Cleopatra VII loved silk, as records and artworks show. Eastern goods spread throughout the civilized world.

During Wang Mang’s reforms, the Western Regions rejected his regime, cutting ties with the East. The short-lived Xin Dynasty fell, and the Eastern Han regained control.

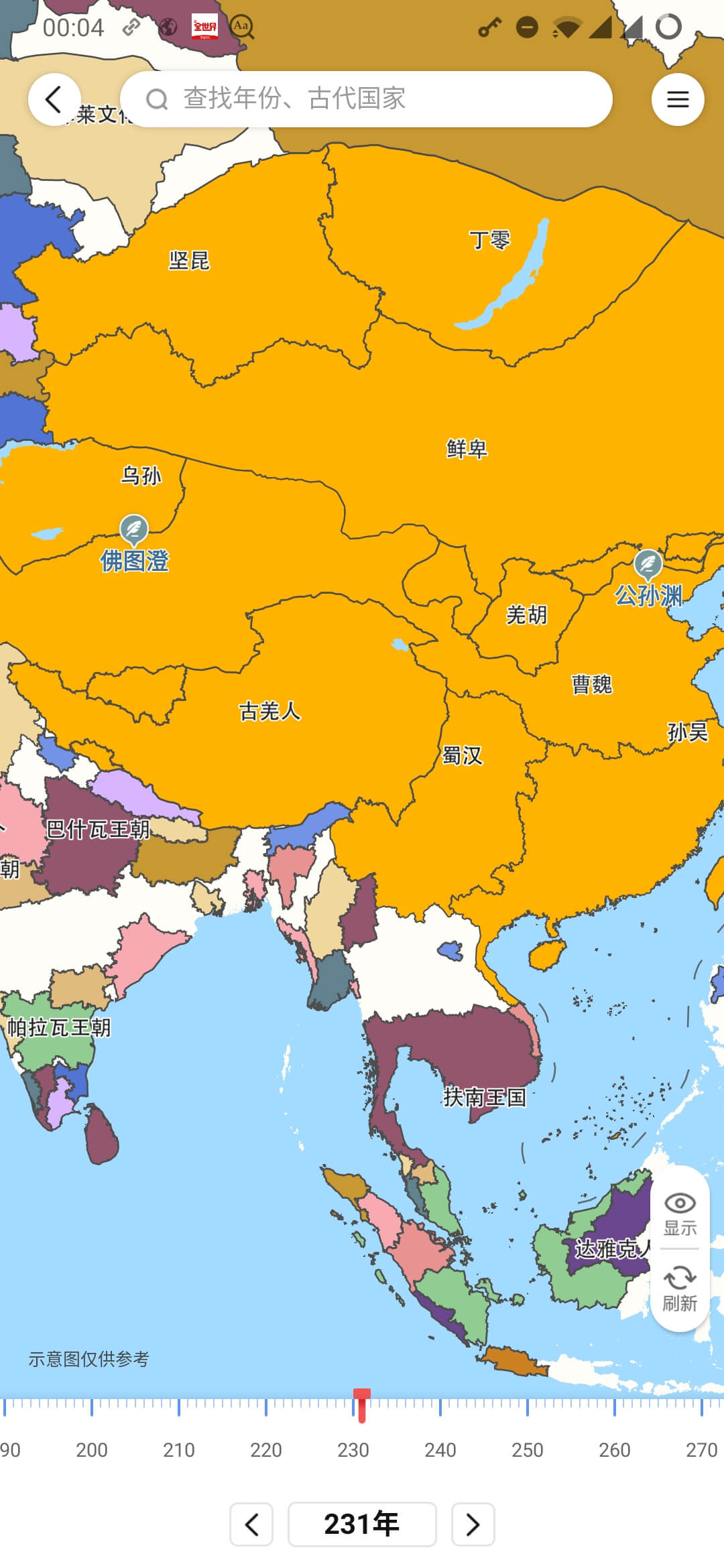

After the Eastern Han, history focuses on the Three Kingdoms, overlooking the Wei Kingdom’s control of the Hexi Corridor and the open Silk Road. It remained generally open through the Wei, Jin, and Southern and Northern Dynasties, despite harassment from the Xiongnu, Xianbei, Rouran, and Turks.

The Sui and Tang Dynasties were the Silk Road’s golden age. Exchanges peaked. Jingjiao (Nestorianism), seen in “The Longest Day in Chang’an,” was introduced to China. The Tibetan Empire, a unified dynasty, arose. They invaded the Hexi Corridor and Western Regions, cutting off the Silk Road. Tang-Tibetan wars lasted nearly 200 years, with the corridor repeatedly lost and regained. Princess Wencheng’s marriage was to appease the defeated Songtsen Gampo. The Tibetan Empire, at its strongest, even captured Chang’an and attacked the southwest, allied with the Nanzhao Kingdom. It eventually collapsed from internal divisions. Zhang Yichao, from Shazhou (Dunhuang), led an uprising, captured the Hexi Corridor, and surrendered to the Tang, reconnecting the Silk Road.

After the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms, the Song Dynasty was too preoccupied with the Liao, Jin, and Western Xia to regain control.

The Yuan Dynasty was brief but unified central China, the Western Regions, and the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau for the first time, solving the Han dynasties’ foreign affairs issues. Unity is key to stability. Even after Genghis Khan, with the Mongol Empire split, civilian exchanges continued. This vast empire was a highway for East-West exchange. Silk Road exchanges continued for over a century under the Yuan. Marco Polo witnessed China’s prosperity during this time.

The Ming and Qing Dynasties were relatively closed, and with rising maritime trade, the overland Silk Road declined. The Qing rebuilt Shazhou City, upgrading Dunhuang, but had little interest in opening it for trade.

Mogao Caves and Buddhism

Dunhuang’s geography and history are just the backdrop. The Mogao Caves and Buddhist culture are its soul.

Buddhism originated in India in the 6th century BC, spreading to China during the Western Han Dynasty. Ashoka made it the state religion of the Mauryan Dynasty, promoting it widely. Many Chinese sites still have Ashoka Temple and Pagoda. Most Eastern civilizations, including the Han, Western Regions, and plateau peoples, accepted Buddhism.

However, India, Buddhism’s birthplace, lost its status. Under colonial rule, it gave way to Persian and Arab religions. Its future shifted east, to Dunhuang. Dunhuang’s rulers represented Buddhist civilization, regardless of wars and changes.

Historical changes might have destroyed the city, but for the Mogao Caves, it was a crucible, forging today’s treasures.

We’ll discuss the Mogao Caves later (Day 3).

Museum

Here are some museum photos. There are many high-definition replicas of Mogao Cave art, for close observation.

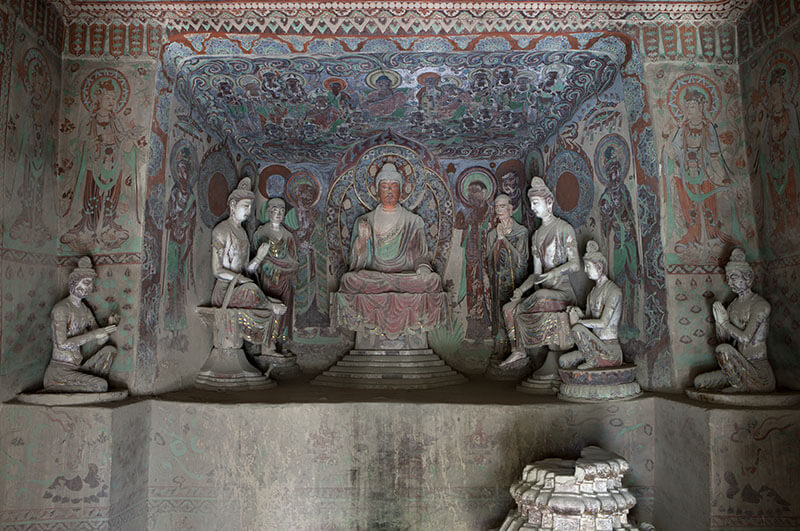

A model of Mogao Cave 45 (High Tang period). The highlight: 7 statues with excellent expressions.

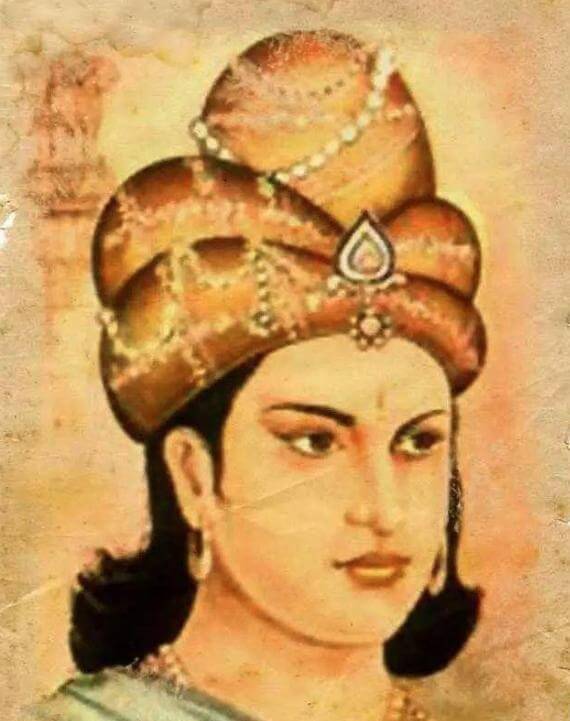

The Bodhisattva statue, the “Beautiful Bodhisattva,” depicts the ideal High Tang female image.

Han Dynasty documents. The beauty of this writing is clear.

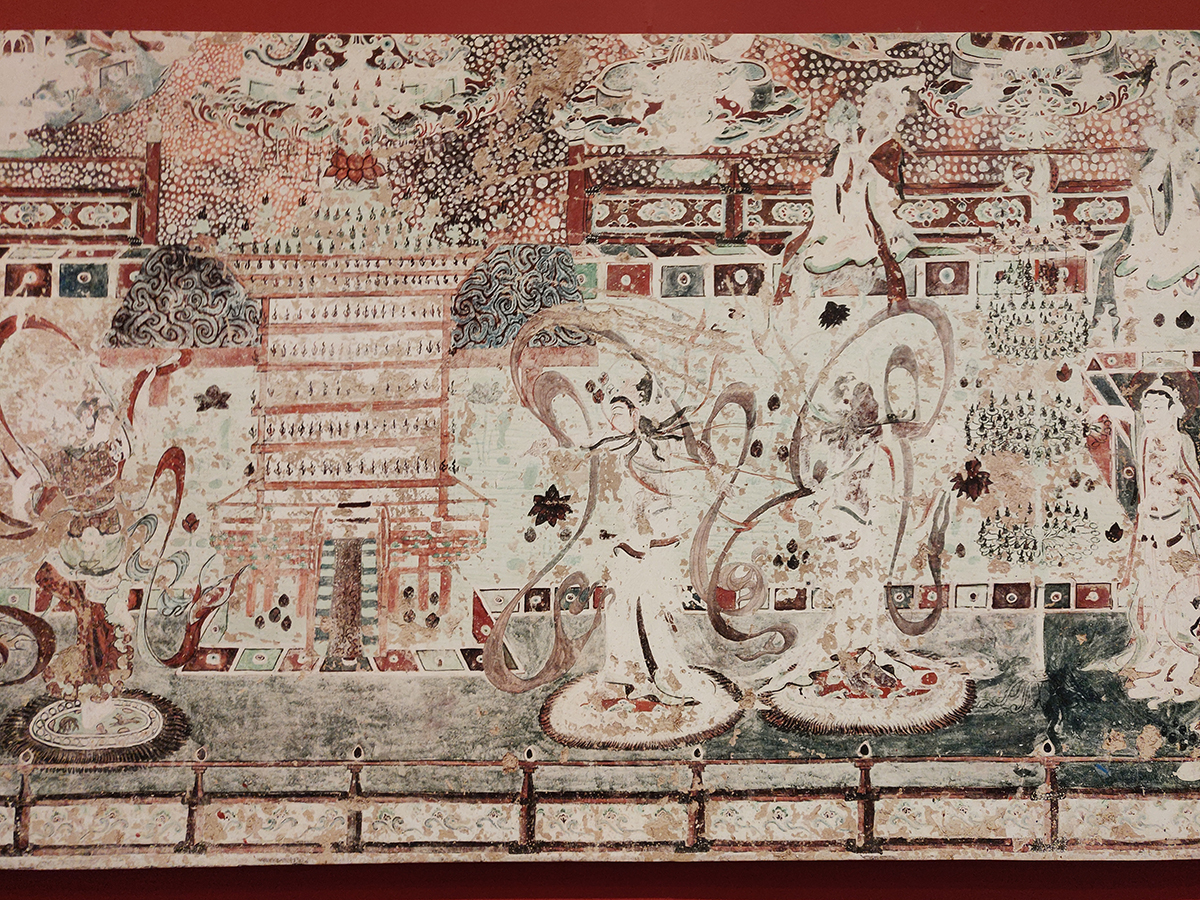

A delicate Buddhist painting: the Nine-Tiered Pagoda of the Three Realms.

I missed photos of other interesting items. Chain mail, unearthed in Dunhuang, was one. Originating in Europe, it appeared in Dunhuang during the Han and Tang, showing surprisingly fast technology transfer. It was precious equipment, worn only by those of rank.

Leaving the hall, we saw a cute modern pixel painting, imitating the Mogao Caves’ Nine-Colored Deer murals.

Day 2: Yumen Pass and Yangguan Pass

We took the western route on day two. The original plan: West Thousand Buddha Caves first (a prelude to Mogao, with more detailed explanations), then Yangguan Pass and Yumen Pass. Finally, Yadan Ghost City for sunset among the wind-eroded rocks.

But Yadan Ghost City had closed last year, reopening to be announced – probably for periodic maintenance.

So, we adjusted: Yumen Pass first, working our way back, hitting as many spots as possible.

The Solar Power Tower

Near Dunhuang, we found a solar power station. I’d noticed neat squares in this area on the map, thinking it was a new tech district.

We detoured to the entrance and found it was a CGN photovoltaic project. For a remote desert city like Dunhuang, clean energy is ideal.

Behind the plant, a tall tower emitted a dazzling white light, with beams converging at the top, like Red Alert’s Prism Tower. It’s a solar thermal station, with thousands of mirrors forming a huge concave mirror. It boils water to drive a steam turbine. Energy efficiency is about 15%, lower than photovoltaics, but it generates AC, easier to connect to the grid.

This bright tower kept us company throughout the day, emphasizing the Gobi Desert’s flatness.

Yumen Pass

After nearly 2 hours, we were surrounded by barren landscape. Some sections had desert vegetation.

Three roads lead into the Yumen Pass scenic area, each to different ruins.

The right road leads to Dafangpan City and a beacon tower, 12 kilometers away, requiring a shuttle bus (fixed times, so you wait). The bus only stops for 30 minutes, not enough for photos and enjoying the view.

Dafangpan City’s full view. A Han Dynasty granary, opening to the south.

A beacon tower on the other side of the road.

Dafangpan City details, some with a Yadan feel. The small holes might be ventilation.

A small lake on the northeast side.

Back at the start, the left road leads to the Han Dynasty Great Wall ruins, 5 kilometers away, also requiring a bus (15-minute visit).

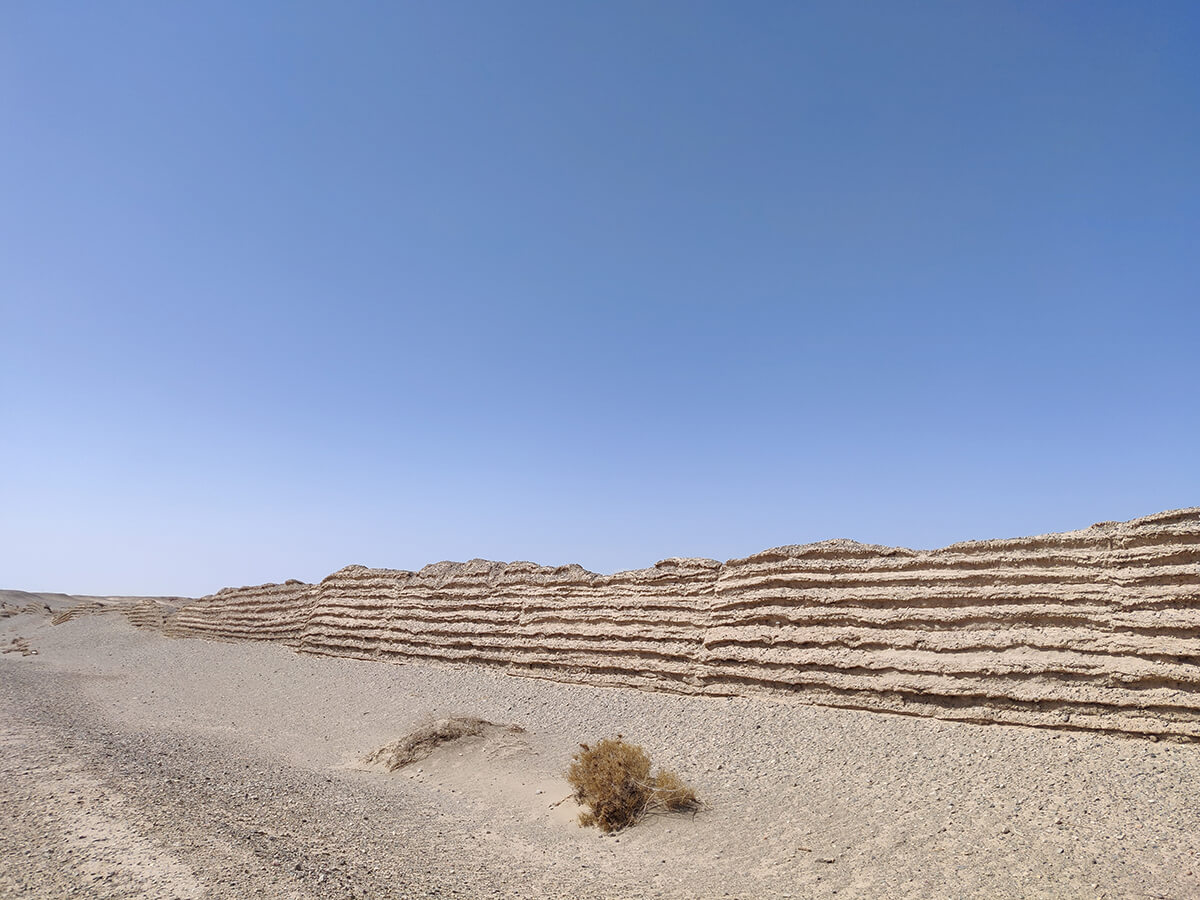

The ruins are shorter than expected, under 3 meters at the highest. The Han Great Wall is 136 kilometers long, from Guazhou to Dunhuang, blocking the Hexi Corridor’s entrance. This 300-meter section is the best-preserved in the country.

Two thousand years ago, soldiers used reeds and gravel to build it in layers. Different weathering rates create horizontal stripes.

One end connects to a beacon tower, always built on high ground.

The Great Wall wasn’t built all at once under Qin Shi Huang, but extended over dynasties. The Han Great Wall was built when Emperor Wu conquered the Western Regions. It included facilities for beacon fire transmission, troop garrisoning, transportation, and farming – a complete defense system.

The beacon fire system appeared as early as the Western Zhou Dynasty (“playing with the feudal lords with beacon fires”). The Han system was complex, with different signals for different situations, materials, and times of day.

Petrified firewood, seen in the museum. Soldiers collected reeds and Salix matsudana branches (unlike weeping willows, these grow upwards). They were plastered with mud for stability. The layered structure is visible.

Returning from the Han Great Wall, one road leads to Xiaofangpan City (Yumen Pass), a small castle and the scenic area’s core, just a few minutes’ walk.

The interior isn’t large, but you can stand on the wall.

A close-up of the outer wall, made of reeds and sand.

North of Xiaofangpan City, a modern observation deck lets you experience looking north. It’s flat between the tower and mountains, making it easy to spot enemies.

Yangguan Pass

Yangguan Pass has few ruins, mostly reconstructions. Siege weapon models are displayed in front of the antique-style pass.

Wang Wei’s line “West of Yangguan, there are no old friends” is literally true. Yangguan Pass was a border crossing, requiring a pass (equivalent to a passport). “Guanzhao” (关照) originally meant a pass, but soldiers would protect those with passes, evolving into its current verb meaning.

Beyond this pass, a beacon tower is the only remaining relic. It’s farther than it looks – you’ll need transport (battery cars, donkey carts, horses, camels – different prices).

I recommend riding a camel. The four of us swayed, the setting sun on our faces. The camel bells were the most beautiful part. The Mingsha Mountain camels (visited later) lacked bells. It was near closing, and the wind and bells made the experience vivid.

The handsome white camel leading the way.

The camel team arrived at the beacon tower. Looking back against the light, the scene was desolate and lonely – awe-inspiring.

Don’t rush back; the real highlight is ahead. Walk higher, and the scenery behind the mountain will take your breath away.

That’s my friend, not me.

Looking back, the same desolation.

You can pay extra to have the camels take you along the Yangguan Road, to a valley and sandy area. The guide claimed it’s a well-preserved ancient road.

It’s questionable, as the ancient Yangguan Road led out of the pass. But the stele of the ruins is at the beacon tower, so it might be true. The experience is what matters.

A Gobi traveler in the afterglow, looking like someone heading towards the vast Western Regions. An amazing end to a day on the western route!

Day 3: Mogao Caves

The Mogao Caves are very close to the airport, even closer than downtown Dunhuang. The site is split into two parts. First, you visit the Digital Exhibition Center, where you watch two short digital films, about 10-20 minutes each.

The first film is a regular movie with actors, providing background on Dunhuang’s history and the Mogao Caves. The second is a 360-degree dome movie, which uses digital models to showcase some of the best caves.

The actual caves are about 12 kilometers from the Digital Center. A buffer zone separates the two, and you must take the park’s shuttle bus—private cars aren’t allowed.

Stepping off the bus, the sheer scale of the Mogao Caves is immediately apparent. Over 700 caves exist, with almost 500 containing statues and murals. However, only around 60 are open to the public. Some caves, like those in the photo, were monks’ living quarters and lack murals. Mogao stretches for 1.7 kilometers, and this is only a small part.

Mogao Caves are a World Heritage Site, a national treasure, but what are they? Historically, they served as a temple complex for monks and a place of worship for believers.

During the Northern and Southern Dynasties, a monk named Le Zun arrived at Sanwei Mountain. He witnessed a golden light, “like a thousand Buddhas,” and began carving caves into the cliff face. This marked the beginning of the Mogao Caves.

From that point on, it was like a chain reaction – more monks and believers came to carve caves and create statues. Construction continued from the Northern and Southern Dynasties through the late Tang Dynasty. During the Song and Yuan Dynasties, local rulers maintained the site, but new construction largely ceased.

The cave area is a separate zone; once you exit, you can’t re-enter. You can’t wander freely – your ticket dictates how many caves you can visit. Booking in advance usually gets you an “A” ticket, granting access to 8 random caves with a guide. Caves open on a rotating basis for preservation. The guide unlocks each cave and locks it after your visit, minimizing damage to the murals from temperature, humidity, and light.

Photography is prohibited, so I’ll use official Mogao Caves or online images.

Mogao Cave 29

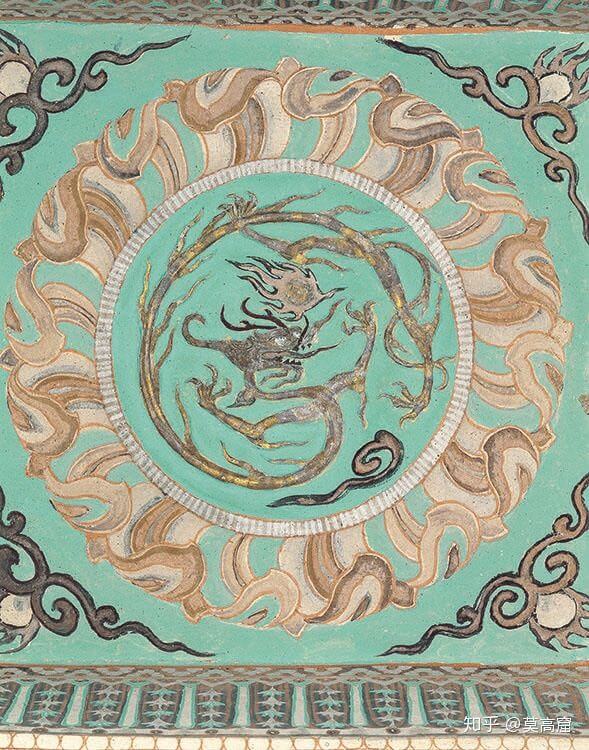

Built in the mid-late Tang Dynasty, with murals repainted during the Western Xia period.

Official introduction: http://tour.dha.ac.cn/content.aspx?id=530741411143zh

This is the caisson ceiling of Cave 29. A caisson ceiling is a recessed decorative ceiling in Chinese architecture, adorned with painted patterns. The vibrant greenish-blue, seen extensively in many caves, comes from malachite green, a natural copper-based pigment.

The Western Xia and the contemporary Uyghurs left behind many caves in Mogao, each with distinct features. The walls are often covered with neatly arranged, repeating Buddha images, representing a thousand Buddhas.

Mogao Cave 329

Built in the early Tang Dynasty, with statues renovated in the Qing Dynasty.

Official introduction: http://tour.dha.ac.cn/content.aspx?id=027193821344

This cave also features a 360-degree VR image from Digital Dunhuang: https://www.e-dunhuang.com/cave/10.0001/0001.0001.0329

Careless Qing Dynasty renovations left these statues somewhat crude, resembling those in a small, local temple. The main draws of this cave are the murals and caisson ceiling. I find the Tang Dynasty murals the most exquisite. Unlike the thousand-Buddha backgrounds of the Western Regions, the Central Plains dynasties’ murals tell stories. These “sutra transformation paintings” (jingbianhua) are a pioneering art form, using paintings to depict Buddhist scripture stories, akin to murals in Western European churches.

The north-side mural depicts Shakyamuni’s birth. Before becoming a Buddha, Shakyamuni was an Indian prince. His mother, Queen Maya, encountered a Bodhisattva riding an elephant descending on clouds. The elephant touched her belly with its trunk, and she became pregnant, giving birth to Shakyamuni from her armpit. The armpit birth relates to the Indian caste system. Shakyamuni’s Kshatriya family, second only to Brahmins, had their caste status associated with the arm.

The south-side mural depicts Shakyamuni’s enlightenment. Witnessing birth, old age, sickness, death, and life’s impermanence, he sought truth and escape from worldly constraints. He rode a horse, with four heavenly kings holding its hooves, and flew over the city wall, escorted by singing and playing apsaras (flying deities) to the mountains for ascetic practice.

The figures’ dark skin is due to the oxidation of the lead-based red pigment used for skin tones. Other colors fade, but the skin tone changes completely, requiring some imagination.

The caisson ceiling is a Mogao masterpiece. The central lotus pattern represents Buddhism’s Western Pure Land. The layered details are rich yet organized. The outermost layer features flying apsaras playing musical instruments.

Flying apsaras are Buddhist deities of song, dance, and flower scattering, capable of flight with just two silk ribbons. They appear in almost every cave, lively and elegant.

On the north wall is a Maitreya sutra transformation painting. Note the technique: figures face forward, while buildings are viewed from above, with a near-large, far-small perspective. This predates Leonardo da Vinci’s perspective painting by almost a thousand years.

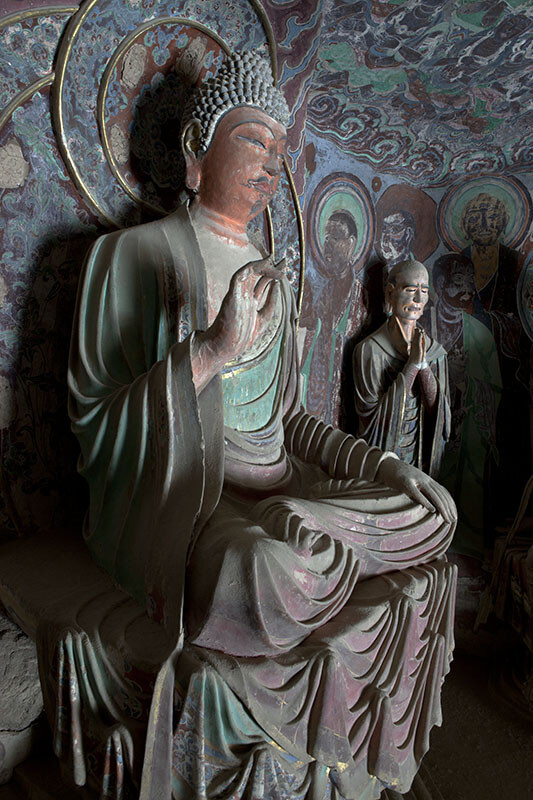

Mogao Cave 328

Built in the early Tang Dynasty, it remains unrenovated, preserving the original early Tang style.

Official introduction: http://tour.dha.ac.cn/content.aspx?id=744635762684

The main Buddha retains the Western Regions beard and hasn’t been completely de-gendered.

On the left is Kasyapa, Shakyamuni’s chief disciple, an ascetic monk with a furrowed brow and solemn expression.

On the right is Ananda, Shakyamuni’s cousin, known as “the most learned” for his memory and long exposure to the Dharma. His expression and posture are more relaxed than Kasyapa’s.

The asymmetrical number of supporting Bodhisattva statues is due to the theft of one by American Langdon Warner; it’s now in Harvard’s Arthur M. Sackler Museum.

Mogao Cave 17

Built in the late Tang Dynasty, this is the famous Library Cave that brought global renown to the Mogao Caves.

Official introduction: http://tour.dha.ac.cn/content.aspx?id=178377696853

Digital Dunhuang VR image: https://www.e-dunhuang.com/cave/10.0001/0001.0001.0017

The door is numbered 16-17, representing two caves. The larger cave was under renovation during our visit. Cave 17 is the small side cave.

The statue of the monk Hong Bian in meditation is a memorial built by his disciples. The mural behind depicts his daily practice, with maids, nuns, a backpack, and a water bottle on the Bodhi tree.

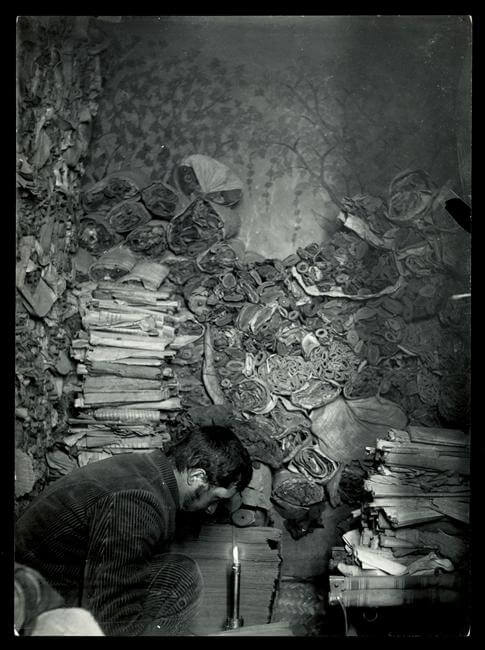

In the early 11th century, the statue was moved, and this cave was sealed with over 50,000 Buddhist scriptures, paintings, and documents, covering over 700 years of social history from the Jin Dynasty to the early Song Dynasty. These are incredibly valuable relics. Two main theories explain the sealing: the refuge theory suggests monks hid the scriptures to protect them from war; the abandonment theory posits they were discarded documents that, out of respect, couldn’t be destroyed, so they were sealed away.

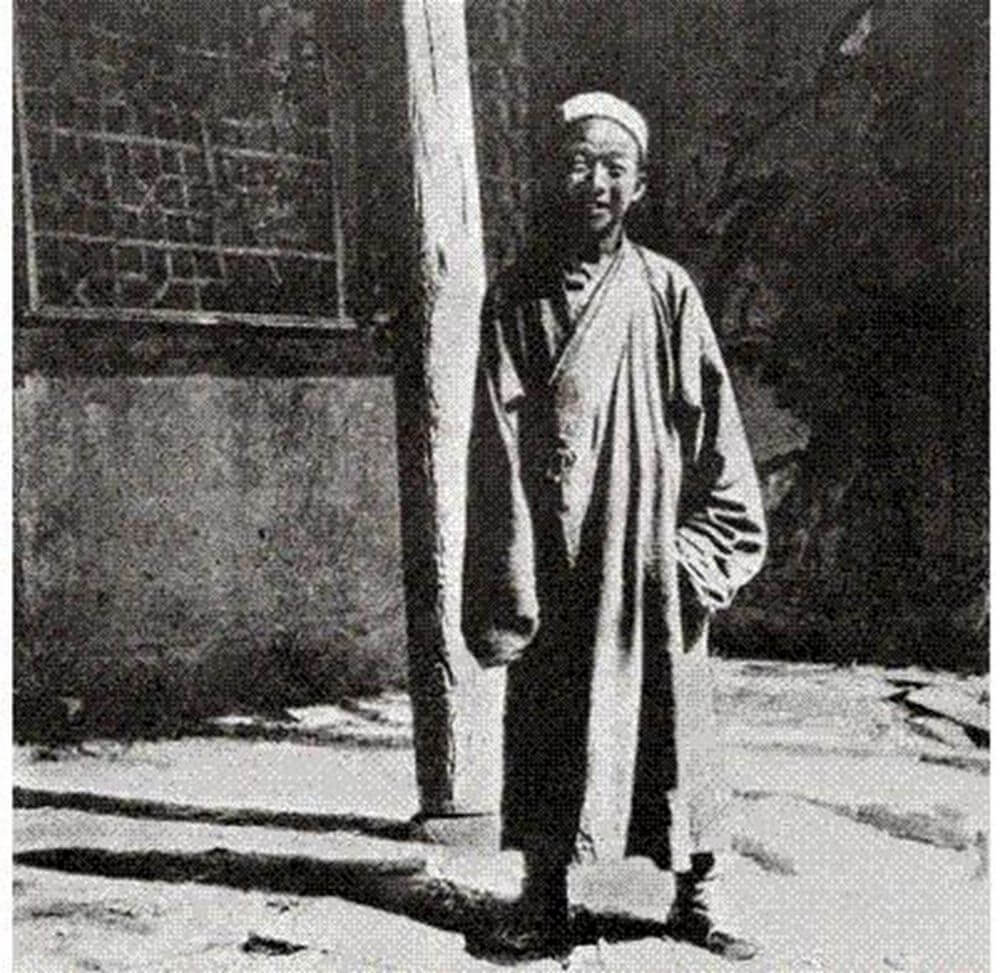

In 1900, a Taoist priest, Wang Yuanlu, was clearing sand. The guide pointed out sand lines on the cave entrance – oblique scratches from accumulated sand rubbing against the wall, the highest almost reaching the door top. Wang Yuanlu noticed a crack in the wall, revealing brick, not rock. He broke through and discovered the 50,000+ relics.

He reported it to the government, but the Qing Dynasty showed little interest in文物 protection. Foreign explorers arrived and bought batches of scrolls at low prices. Over 40,000 of the 50,000+ relics were lost overseas.

A photo of the Library Cave and scrolls taken by American Aurel Stein.

Frenchman Paul Pelliot selecting relics in the Library Cave.

Mogao Cave 292

Built in the Sui Dynasty.

Official introduction: http://tour.dha.ac.cn/content.aspx?id=864712375785

This cave has an innovative layout: three groups of Buddha statues (1 Buddha + 2 disciples each). The front is the present Buddha Shakyamuni, the south is the past Buddha Dipankara, and the north is the future Buddha Maitreya.

Besides the Three Buddhas divided by time, there are Three Buddhas divided by space. The Eastern Medicine Buddha (Pure Lapis Lazuli World) is for present-day well-being. The central Shakyamuni Buddha (Saha World) is Buddhism’s leader. The Western Amitabha Buddha (Land of Ultimate Bliss) guides beings to escape suffering. Some Buddhists believe the Three Buddhas in space are all incarnations of Shakyamuni.

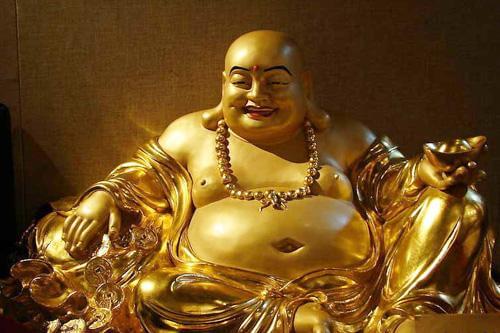

Sui Dynasty Buddha statues differ greatly from Tang Dynasty ones, lacking realistic proportions and having large, square heads. The past Buddha Dipankara and future Buddha Maitreya have similar images. The common big-bellied Maitreya image is based on a later cloth bag monk.

The commonly seen Maitreya Buddha statue today.

The cave’s top features a pair of lions, now humorous due to oxidation, making them look lightning-struck.

Mogao Cave 61

Built during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.

Official introduction: http://tour.dha.ac.cn/content.aspx?id=816484388973

Digital Dunhuang VR image: https://www.e-dunhuang.com/cave/10.0001/0001.0001.0061

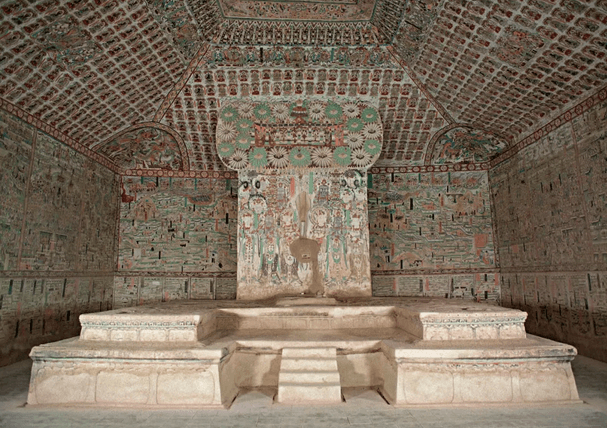

This cave has a horseshoe-shaped altar, but the Buddha statue is destroyed. A lion’s tail shape at the remaining connection suggests it enshrined Manjushri Bodhisattva, whose mount is a lion.

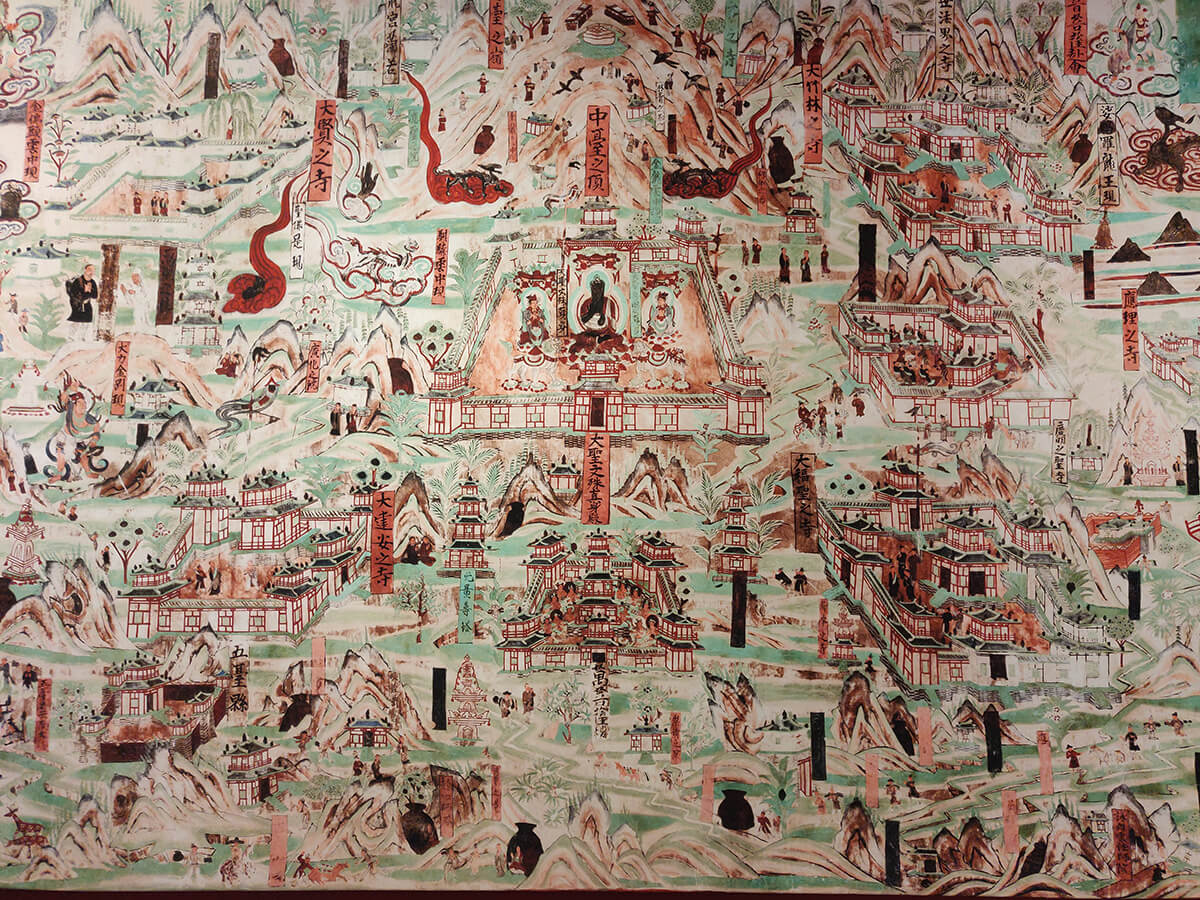

Behind the altar is a massive “Map of Mount Wutai” (Manjushri’s dojo), 13 meters long and 3.6 meters high, detailing roads to Mount Wutai, Buddhist pilgrimages, and local life. I saw a high-definition replica in the Mogao Caves Art Museum (these two pictures are from there).

Another highlight is the donor mural near the entrance. This cave was a merit hall built by secular believers, so the donors are like sponsors’ logos – prominently displayed.

After the Tibetan Empire’s decline, Zhang Yichao established the Guiyi Army, seized Dunhuang and Guazhou, and submitted to the Tang. The Cao family, the second ruling family of the Guiyi Army, built this cave. The murals depict Cao family women, their peach-shaped hairstyles indicating Uyghur identity. Uyghur is a Turkic language, and its pronunciation is close to that of the modern Uyghur ethnic group.

Picture from the art museum. Left: Uyghur lady married into the Guiyi Army. Second from left: Han Chinese, but married into the Uyghur regime and dressed in Uyghur attire. Third from left: Different hairstyle, a woman from Khotan (a Buddhist regime in today’s Hotan, Xinjiang). This shows the Guiyi Army’s delicate balance through marriage alliances. The fourth from the left, taller and in Han attire, is the family’s true mistress, but she yielded the first three positions out of courtesy.

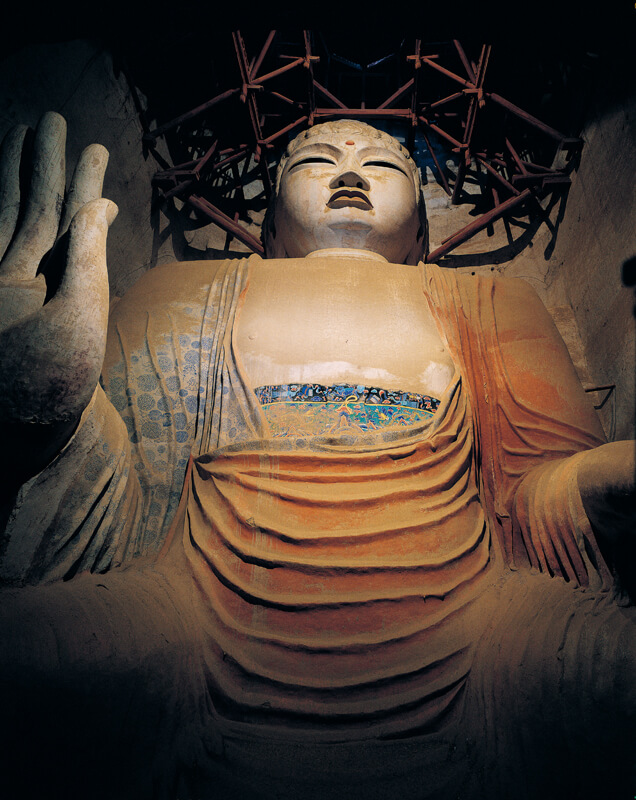

Mogao Cave 96

Built in the early Tang Dynasty and commonly called the Nine-Story Building, this is the largest structure in the Mogao Caves.

Official introduction: http://tour.dha.ac.cn/content.aspx?id=525124140728

It’s magnificent from the outside, fully utilizing the cliff’s height.

Photographed by Warner in 1924. The external building had vanished; only the cliffside Buddha statue remained after thousands of years. The current building is a reconstruction.

The 35.5-meter-high statue of Maitreya Buddha is China’s largest indoor Buddha. Carved from the cliff, its details were created with plastered mud. It’s a stone-core clay statue, unlike the smaller clay-core statues.

The Buddha’s left hand, palm up, is the Varada Mudra (fulfilling wishes – compassion). The right hand, palm forward, is the Abhaya Mudra (removing suffering – mercy). Compassion and mercy are distinct.

Mogao Cave 148

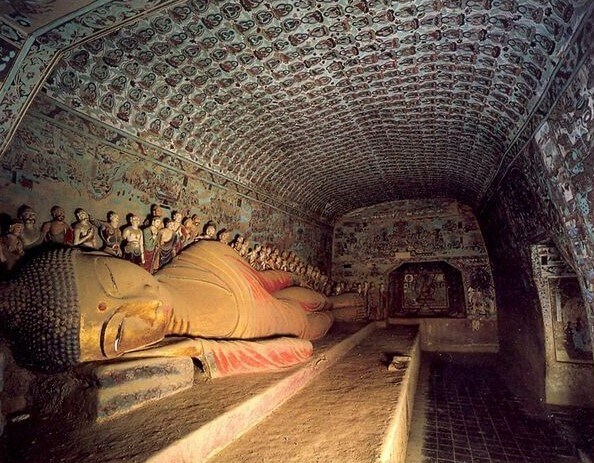

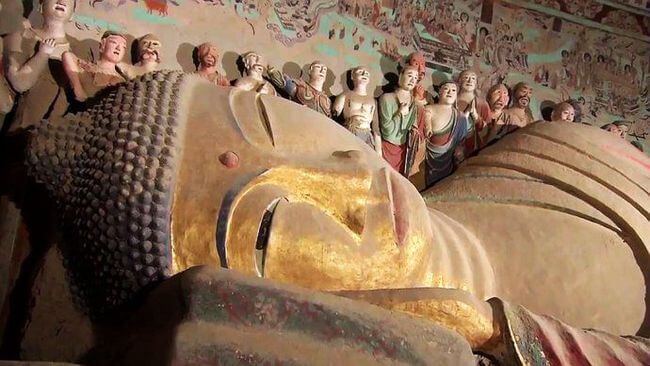

Built in the High Tang Dynasty, renovated in the late Tang, Western Xia, and Qing Dynasties, this is Mogao’s largest reclining Buddha cave.

Official introduction: http://tour.dha.ac.cn/content.aspx?id=659662000840

The delicate, natural clothing folds reflect High Tang Dynasty customs.

Reclining Buddha statues depict Shakyamuni’s death, signifying his escape from reincarnation and suffering. This is the Nirvana Buddha, and the cave’s shape echoes this, with a coffin-lid-like top.

Densely packed disciples and believers show sadness. The guide noted one (not pictured) with higher understanding, smiling, happy for the Buddha’s Nirvana.

The three walls feature a huge Nirvana sutra transformation painting, depicting events before and after Shakyamuni’s Nirvana: 66 scenes, 500+ characters and animals – a masterpiece.

Part of the Nirvana sutra transformation painting (from the art museum). Four strong men carry the body, with Bodhisattvas, monks, and believers seeing them off.

The body was cremated, and the Buddha’s relics were distributed for safekeeping and worship.

Art Museum

Visiting the caves is rushed, for preservation, minimizing human impact. The explanations are roughly equivalent to this travelogue’s content, hard to remember fully. I recalled this information gradually after returning and researching.

Therefore, visiting the Mogao Caves Art Museum afterward is essential. Here, you can calmly examine details.

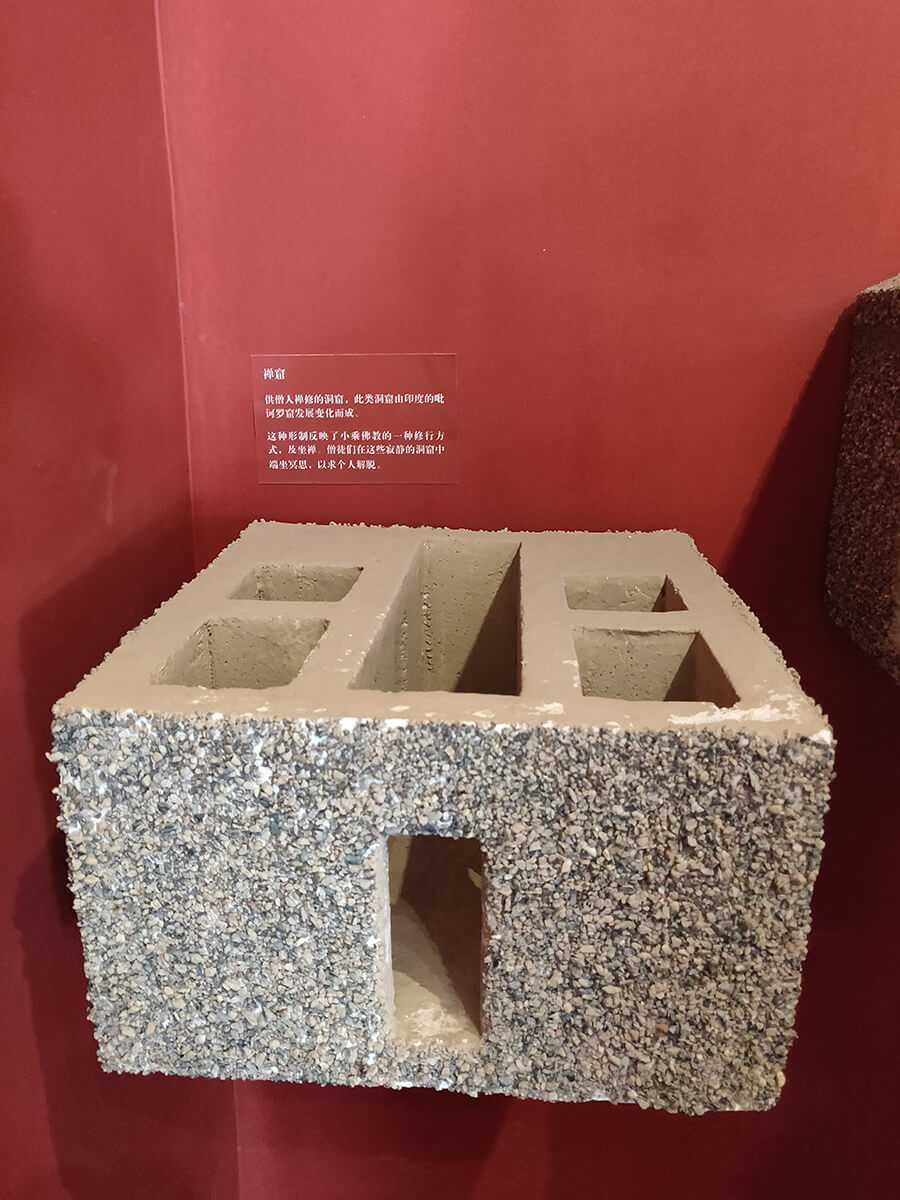

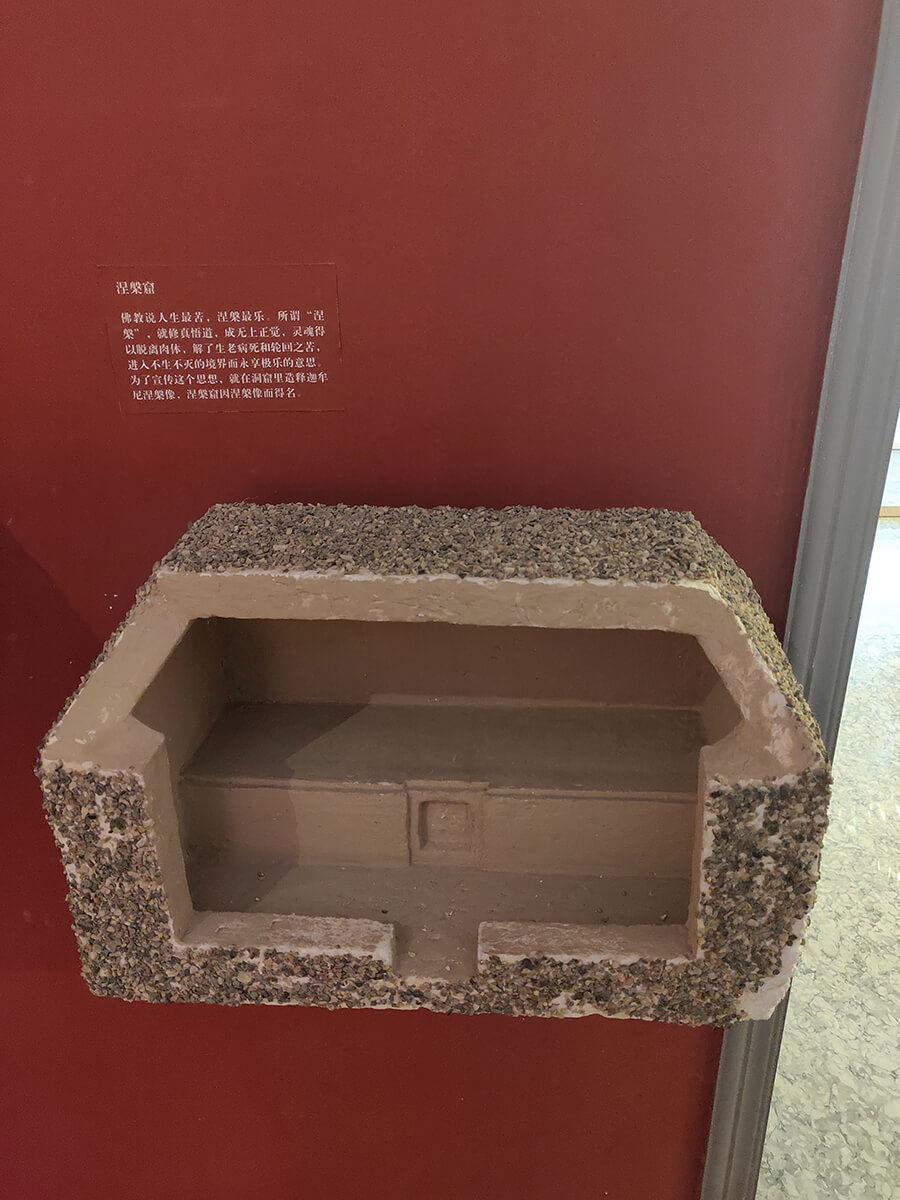

The museum displays models of typical caves, representing different architectural forms.

Zen caves: monks’ living quarters, without statues or murals.

Central pillar caves: usually large, with a truncated pyramidal front roof and a flat back roof. Believers circumambulate the central pillar.

Hall caves: similar to central pillar caves, but without the pillar; the statue is in a front wall niche.

Central altar caves: large dome, no pillars, an altar instead of a pillar.

Nirvana caves: rectangular, coffin-shaped, themed around Buddha’s Nirvana.

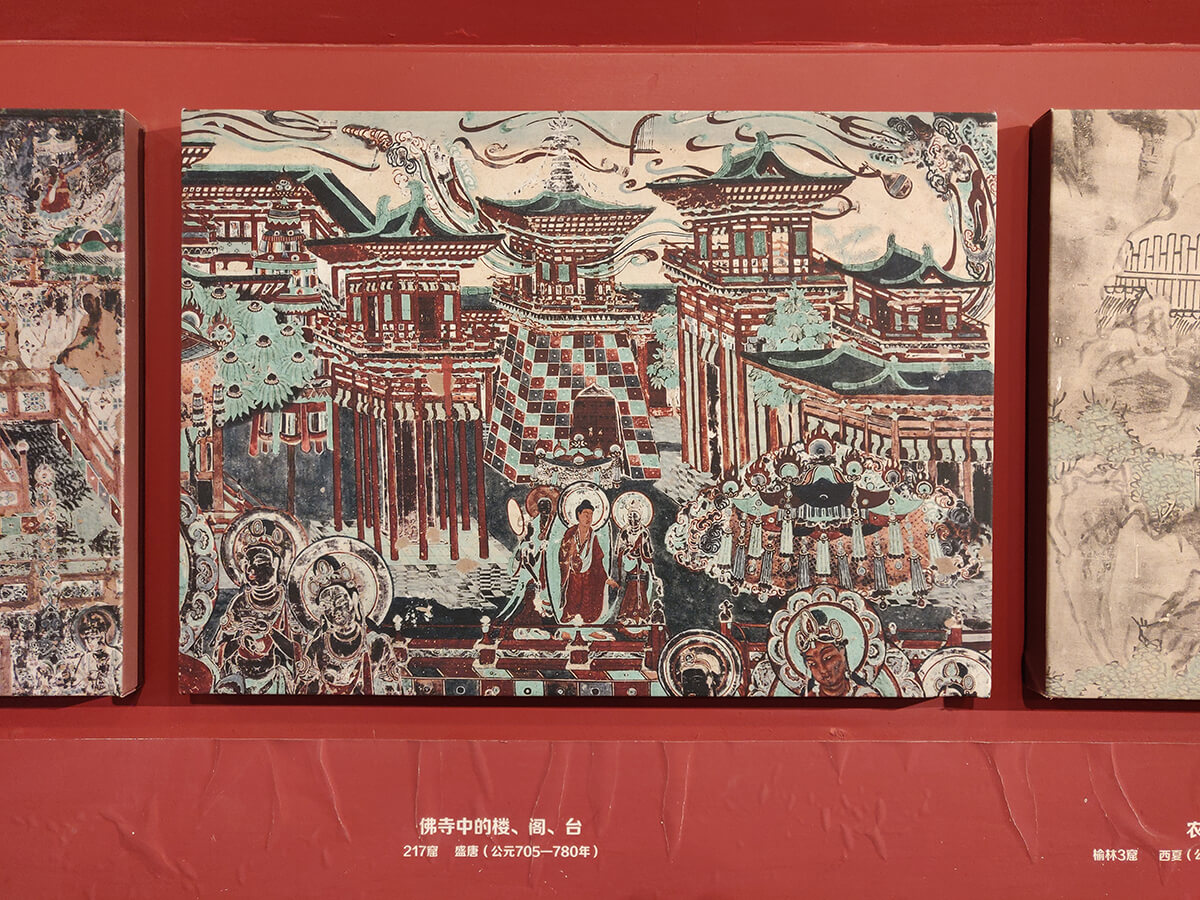

The murals depict numerous buildings from different periods.

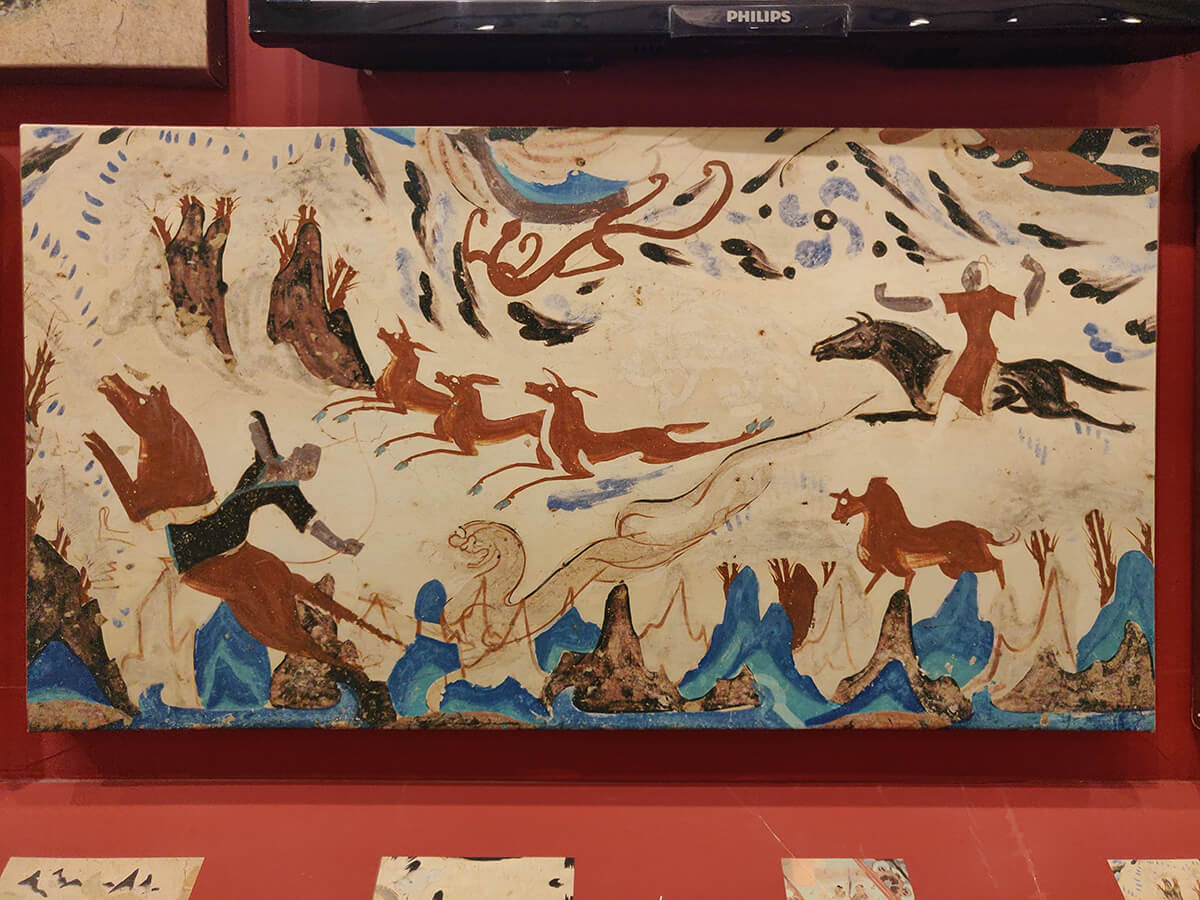

And scenes of secular life, like this hunting scene.

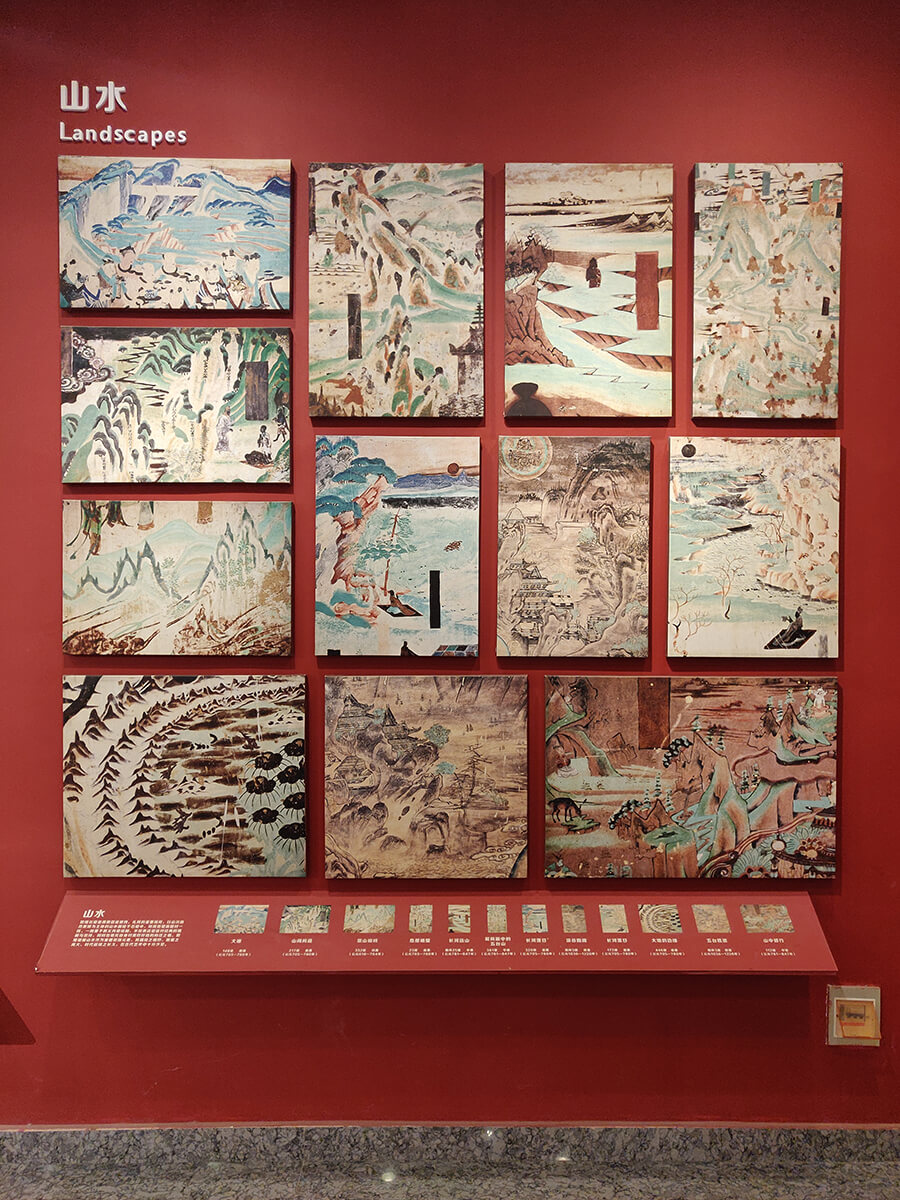

Also, landscapes.

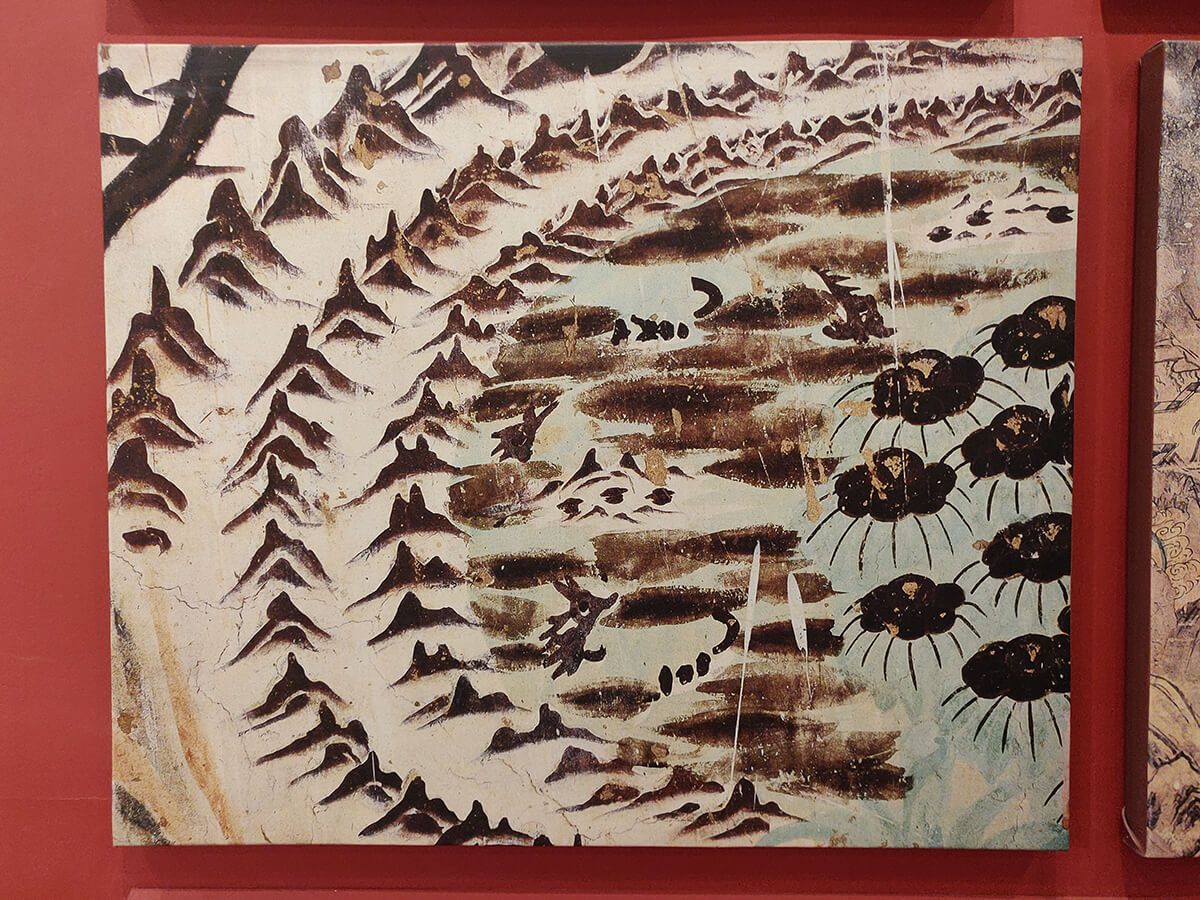

One depicts the end of the world.

Murals are also key for studying makeup. Tang Dynasty women shaved their eyebrows and repainted them, unlike other dynasties.

Scenes of music and dance.

Clothing, hairstyle, and dance posture indicate this is the Hu Xuan dance of the Western Regions, which appeared in Tang Dynasty celebrations, reflecting frequent cultural exchange.

These are imaginations of celestial music: instruments sounding without human players.

War scenes, too. This group shows Zhang Yichao’s army recovering Shazhou and Guazhou.

The most interesting are Buddhist stories. This is the Nine-Colored Deer, one of Shakyamuni’s previous lives. It saved a drowning man, who promised secrecy. The queen dreamed of the deer, and the king offered a reward. The man, tempted, revealed the secret. The deer, surrounded, told the king the truth. Moved, the king forbade harming it. The ungrateful man was covered in sores.

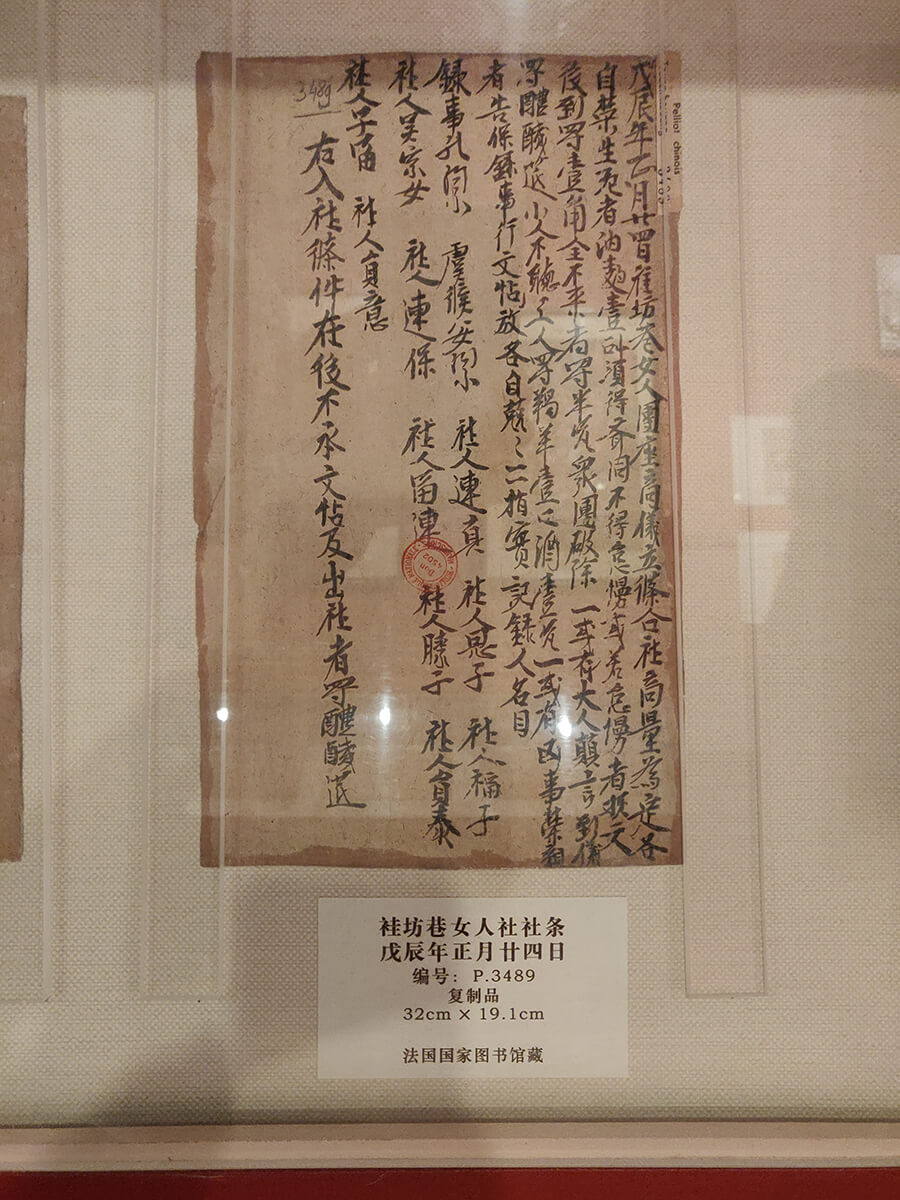

Besides murals, there are other relics. This “Rules of the Women’s Society of Guifang Lane” was a Tang Dynasty folk organization with membership rules and signatures. It was entirely female, evidence of Tang Dynasty openness.

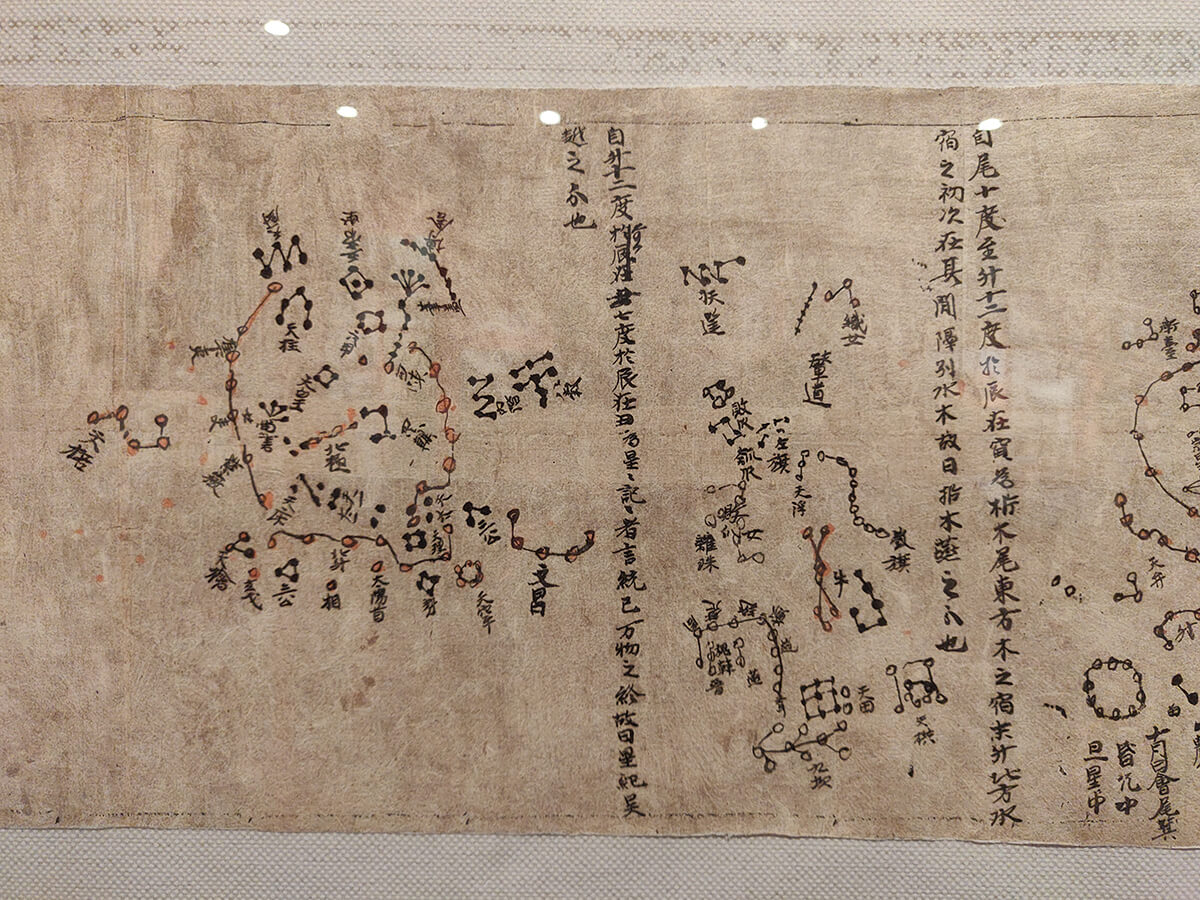

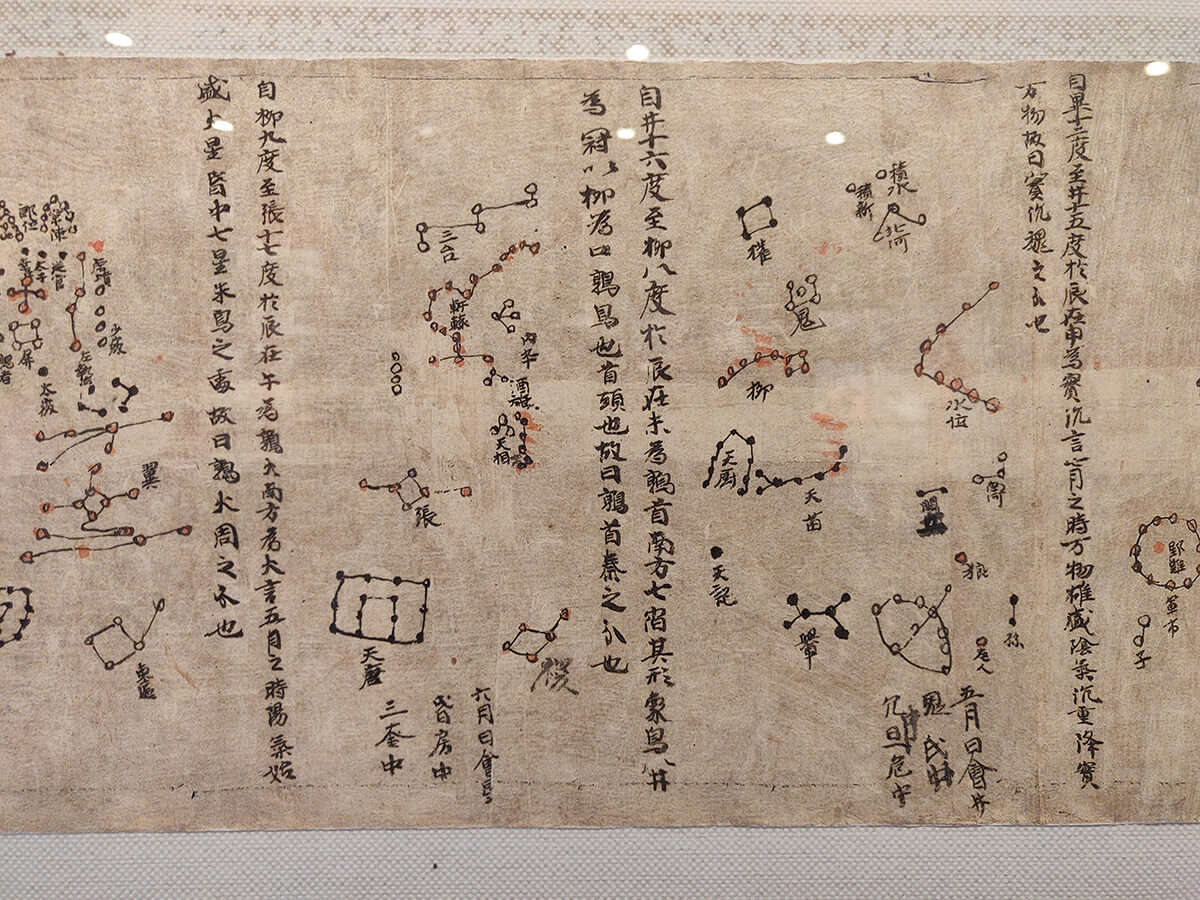

A long star chart scroll, very different from modern constellations. I only recognized Vega.

Leaving the museum, returning to the bus stop. Looking east, across the valley, is Sanwei Mountain, where Le Zun saw the thousand Buddhas.

I was told at Yangguan Pass that the Mogao Caves might close permanently in three to five years for maximum mural protection. Tourists would then only see digital reproductions. Whether true or not, closure will happen eventually. I hope digital visits can better showcase its charm.

The Digital Dunhuang website, mentioned earlier, is a treasure trove with VR images of representative caves: https://www.e-dunhuang.com/index.htm.

The 2008 NHK documentary “The Full Beauty of Dunhuang” (about 3 hours) is also well-produced: https://v.qq.com/x/page/c052998o5ua.html.

“Encore Dunhuang” Performance

That evening, I saw the “Encore Dunhuang” performance. Many historical, cultural, or folk custom sites have performances; “Encore Dunhuang” is truly special.

The venue is next to the Mogao Caves scenic area.

It’s a large-scale recitation performance, communicating with ancient Dunhuang souls through a modern guide’s perspective, traversing millennia. Uniquely, for the first hour of the 1.5-hour show, the audience has no seats. They follow the plot, moving through historical scenes, experiencing major Dunhuang events up close.

I didn’t take pictures; it must be experienced. The most shocking scene, for me, was Wang Yuanlu transporting relics. The Bodhisattva manifested, and numerous flying apsaras broke through the wall, vividly restoring the Bodhisattvas’ solemnity and the apsaras’ agility.

Stargazing

After the show, I was still itching for something to do. With all the sites closed, I looked for some natural beauty.

We drove about 20 minutes out of Dunhuang, taking a small dirt road off the highway. We had no idea where it led; it was pitch black. We cut the headlights; only a faint glow from Dunhuang remained on the horizon. Obviously, 20 minutes wasn’t nearly enough to escape the light pollution.

Still, the stars were much better than anything in Hangzhou. No Milky Way, but they were the brightest I’d seen in over a decade, rivaling the skies from my childhood in Nanchang. Every star in the Big Dipper outshone Jupiter in Hangzhou’s night sky. I used the Dipper to locate Polaris, but it was dimmer than the seven, meaning there were some clouds. Conditions weren’t perfect.

No matter – the next day at Mingsha Mountain, we saw an even clearer sky.

Day 4: Mingsha Mountain and Crescent Spring

Our plan to visit Baima Pagoda, a lesser-known attraction, was thwarted by road construction.

Leiyin Temple

Since it was the first workday after the Qingming Festival, we headed to Leiyin Temple near Mingsha Mountain. It’s a modern temple, not ancient. The spacious grounds and widely spaced buildings, with minimal landscaping, give it a palace-like feel – quite unlike the compact, nature-filled temples of Jiangnan.

Some halls are built in the Tang Dynasty style, featuring traditional dougong (bracket sets). Others are in the later Ming and Qing styles.

Tang Dynasty dougong. (Image source: internet)

It’s a pleasant spot to unwind, but not essential.

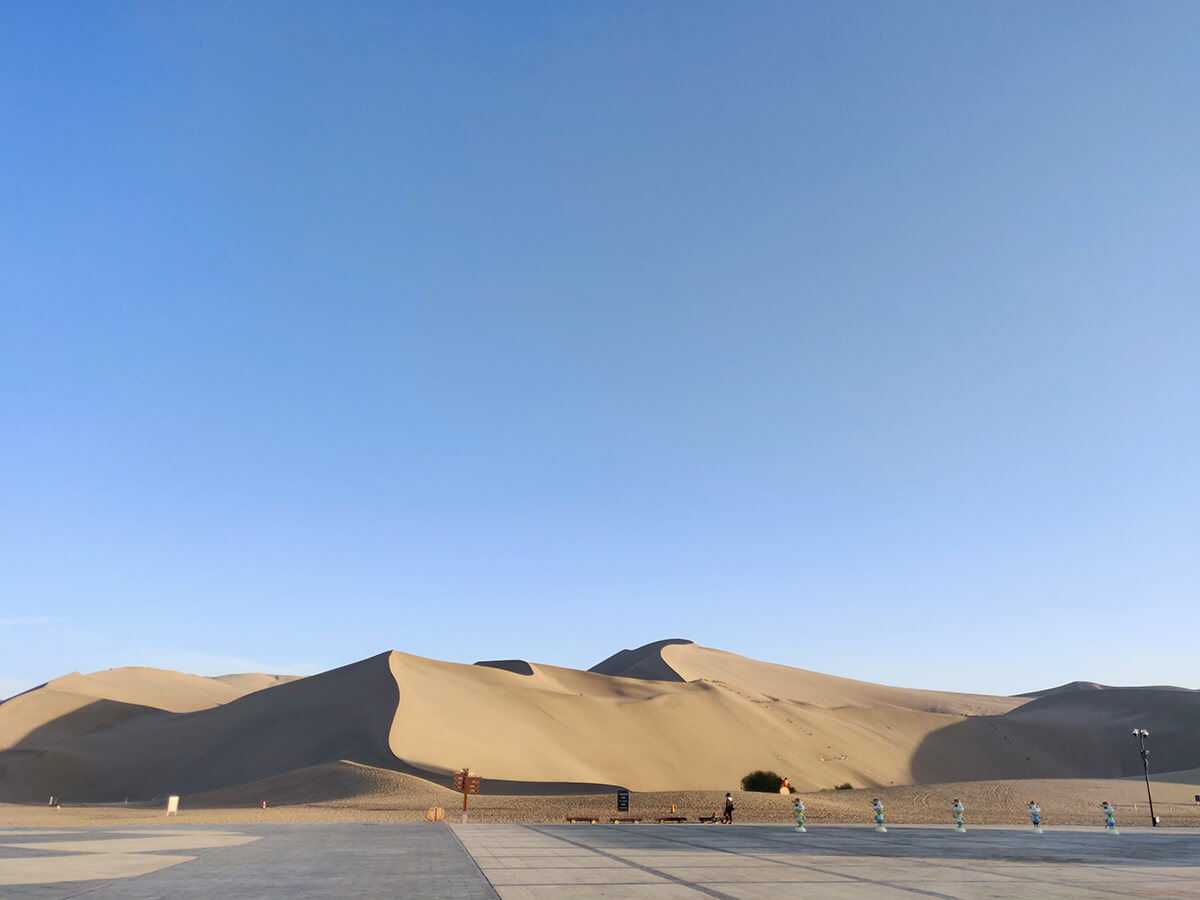

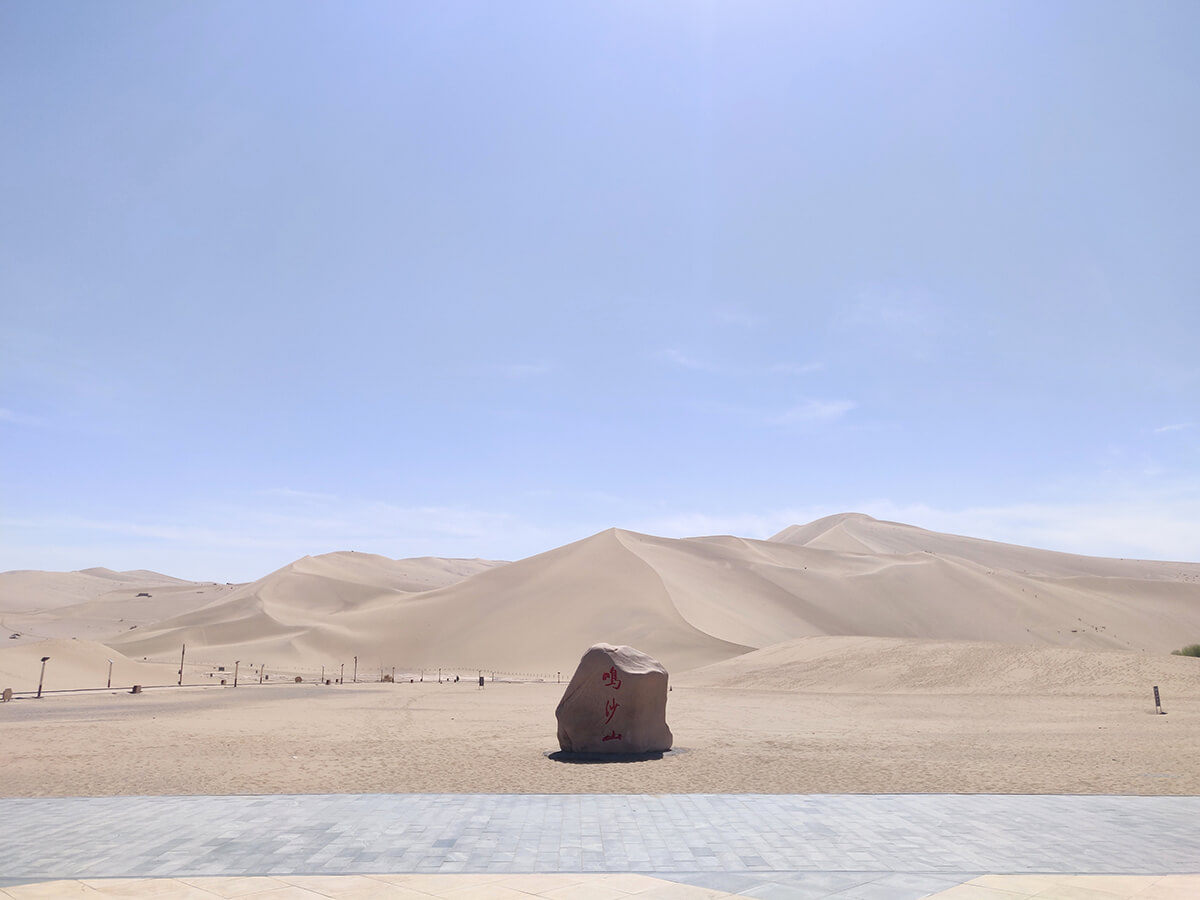

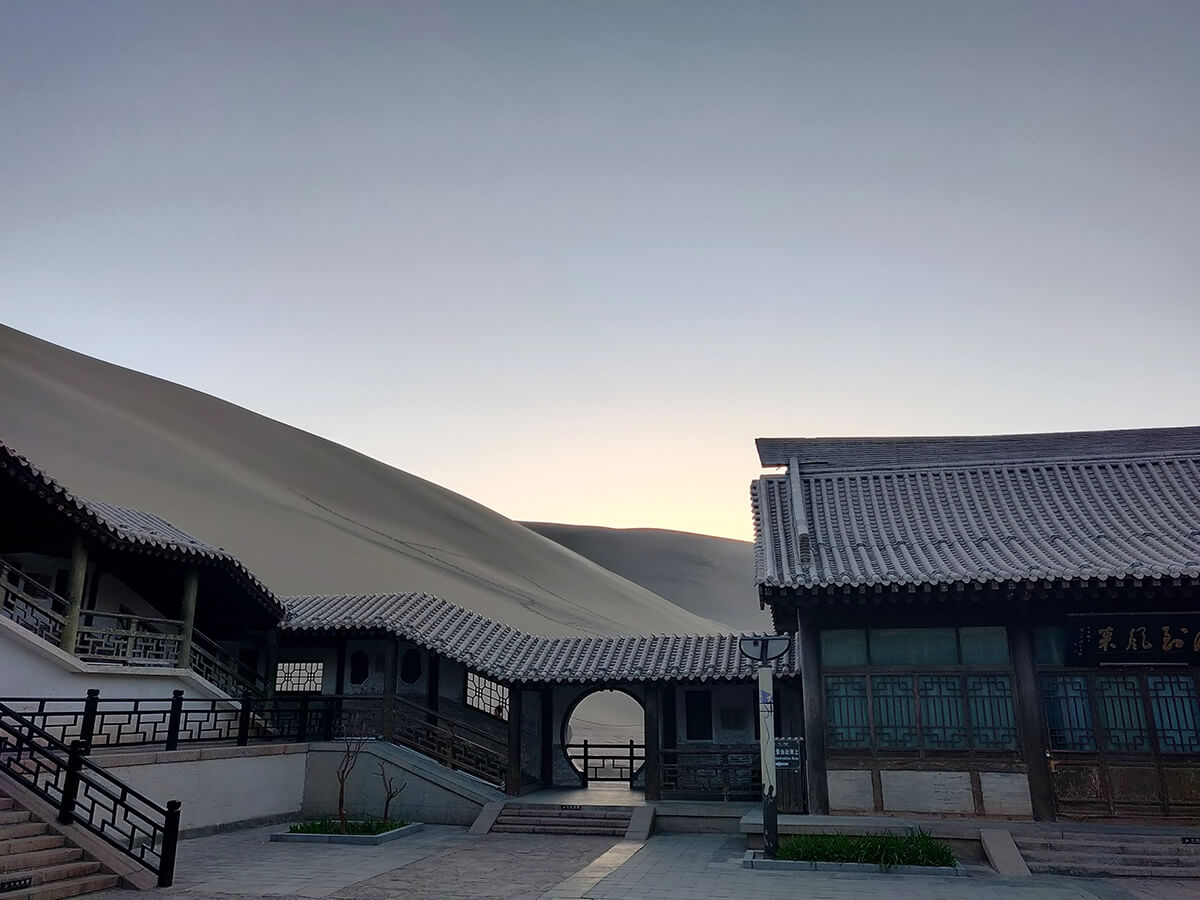

Mingsha Mountain (Singing Sands Mountain)

Mingsha Mountain and Crescent Spring are two separate areas. Mingsha Mountain is where the action is: camel rides, dune buggies, and gliders. We tried them all, and it’s worth experiencing the desert from different angles.

Unlike the rocky Gobi on the West Line, here it’s all sand dunes.

As a Southerner on my first Northwest trip, I was mesmerized. I’d never seen anything like it.

The dune buggies were the best value. A pro driver accompanies you, but you can take the wheel on flatter sections. It’s tough to steer on sand; the wheels drift, requiring real effort to keep straight. We probably hit 40 km/h, and many sections were sloped – a real thrill.

Only this activity lets you pay extra to access a special area. Atop the mountain, there’s a desert botanical garden, with low-lying plants spread across the valley – a stark contrast to the dunes.

My friend’s silhouette. The desert’s charm is palpable.

These plants are almost person-high up close.

The buggy ride includes sand sliding at Jade Maiden Peak, offering panoramic views: Dunhuang city to the north, Gobi mountains to the east, and dunes to the west and south. The peak has steep, almost 60-degree slopes. Sand sliding is surprisingly safe; the friction is high, requiring effort to move even on steep inclines.

Mingsha Mountain (Singing Sands Mountain) gets its name from two sound phenomena. Strong winds create a rumble, reportedly audible in Dunhuang city. Sliding down the dunes also produces a hum, especially noticeable with multiple people. The exact cause remains a mystery.

Next, we took a glider. It’s powered, with a rear propeller, taking off from a small airstrip. The flight circles Mingsha Mountain for about two minutes, passing over Crescent Spring.

From above, Crescent Spring resembles jade inlaid in the dunes.

Camel riding was next, though I didn’t take photos. Hundreds of camels rested at the camp – a unique sight. The ride passes several photo spots before returning, taking over an hour. Having tried the other activities, and ridden camels at Yangguan, it was less thrilling. Still, desert camel riding is a distinct experience. The constant stream of camel trains at Mingsha Mountain creates a Silk Road caravan ambiance.

Crescent Spring

We headed to Crescent Spring, hoping for a sunset view.

The angled sunlight creates sharp light/shadow lines on the dunes, enhancing their three-dimensionality.

We miscalculated. Crescent Spring, fed by an underground river, lies in a depression surrounded by dunes. Reaching the edge, we realized the sun was already blocked.

The buildings near Crescent Spring felt like a paradise: flowers blooming within the walls, contrasting with the vast desert outside.

Walking the corridor, I kept expecting a Jiangnan garden landscape outside each window – a surreal feeling.

From the tallest building, you can see fish in the crescent-shaped lake.

A friend captured Crescent Spring’s transition from day to night.

Crescent Spring at twilight: incredibly peaceful.

Dunes illuminated by twilight.

After dark, stars emerged. Despite the light pollution, the clear sky offered excellent viewing. My phone captured this; imagine the naked-eye view.

A bonfire party campsite lies over 10 kilometers behind Crescent Spring, accessible with a camping package. It’s reportedly a good stargazing spot.

Day 5: Heading Back

No activities were planned. We returned the car and flew out at noon, with a 3-hour layover in Lanzhou, arriving back in Hangzhou that night.

We lucked out with the weather, avoiding sandstorms. A heavy sandstorm greeted us on arrival, but it cleared by evening. The weather improved steadily, only to worsen again two days after we left. I forgot to update my weather app and saw Dunhuang’s weather turning. The small square in the center is Dunhuang city.

Spring in Dunhuang is beautiful, but unpredictable.

A week after returning, I still dreamt of the Gobi Desert and the Buddha murals.

Tips for Dunhuang

Having planned the entire trip myself, from flights to hotels, here are some practical tips based on my experience:

City Life

Dunhuang is a surprisingly clean desert city. You get the natural beauty of the Northwest with the tidiness of a major city.

Water isn’t as scarce as you might expect. A reservoir supplies the city, and a good-sized river runs through the center. Parks along the river even have a Jiangnan feel.

Dunhuang is two hours behind Beijing time. Sunset in spring is around 8 PM. While 2 AM feels like midnight and 10 AM feels like 8 AM, attractions and restaurants generally operate on Beijing time, especially in the off-season. Most places close after 9:30 PM Beijing time, leaving only the night market and some late-night BBQ spots. Plan accordingly if you want both sunset views and a proper dinner.

At about 1200 meters above sea level, altitude sickness isn’t a concern.

Forget outdated online guides claiming poor network coverage on the West Line (Yumenguan, Yangguan) and the need for cash. Mobile payment is standard in this tourist city.

Climate

Dunhuang experiences significant temperature swings, up to 15-20 degrees Celsius between day and night. In early April, it’s pleasant, nearing 20 degrees at noon, and hotter in the desert. Nights are around 5 degrees and chilly with wind.

For a spring visit, pack for both spring and winter conditions. Avoid mesh shoes or clothes – you’ll be shaking out sand forever.

The desert sun is intense, even in spring. Sun protection is crucial: hats, sunglasses, and scarves are a must. Sunscreen is essential for the ladies.

Even dressed like this, I ended up with a tan resembling a Dunhuang mural.

Peak season is July and August, with scorching daytime temperatures.

Food

This section is time-sensitive (2021). Restaurant brands may change.

Local specialties include donkey meat with yellow noodles (驴肉黄面) and braised mutton with pancakes (胡羊焖饼). Expect lots of donkey meat, mutton, and noodle dishes. Shacong (沙葱) is a tasty local vegetable, often served in a cold salad. Apricot peel water (杏皮水) is the local drink, similar to sour plum soup. Xinjiang and Sichuan cuisine are also widely available.

Our first meal was at the Shazhou Night Market – a tourist trap with mediocre food. We found much better options later.

We asked locals for recommendations, and they pointed us to highly-rated restaurants on Dianping (大众点评, a Chinese review app). Dianping is a more reliable source than the local tourism bureau.

Cheng Bianbian BBQ (城边边烧烤): A popular BBQ joint, open late – expect a queue. The grilled meats and lamb chops are excellent, with a unique, slightly sour flavor (vinegar in BBQ is new to me!). Their fresh fruit yogurt is also worth trying.

Huoyanyan BBQ (火焱焱烤肉): BBQ and Xinjiang cuisine, also open late. We went around 9 PM without waiting. We recall two noodle dishes: Xinjiang beef rice noodles and a soupy noodle dish (name forgotten).

Daji Jiang Donkey Meat Yellow Noodle Restaurant (达记酱驴肉黄面馆): A traditional, old-fashioned restaurant with waiters who look to be in their 50s. They likely only serve lunch and dinner. The yellow noodles and donkey meat are far superior to those at the Shazhou Night Market. The donkey meat is thickly sliced, and the noodles aren’t overly sour.

We mostly ate at Dicos and KFC otherwise, due to time constraints. Dicos is prevalent in Dunhuang.

Two other noteworthy mentions:

- A small pastry stall at the Shazhou Night Market food street entrance serves breakfast. The grilled corn cakes are delicious, reminding my friends from Northeast China of their childhood.

- “Liu Ajing” (刘阿晶) is a ubiquitous local milk tea brand. Their signature 3-yuan large ice cream cone is rich and creamy – I had it three times in five days.

Accommodation

Two main lodging options exist: near the Flying Apsaras statue (反弹琵琶雕像) in the bustling city center, close to the Shazhou Night Market; or near Mingsha Mountain, offering convenient sightseeing and scenic views.

Dunhuang is small, with most high-rises being hotels. A south-facing window guarantees a view of Mingsha Mountain, varying only in distance.

We stayed at the Bohui Wenhua Hotel in the city center, near the commercial district. It’s 3 kilometers from Mingsha Mountain, but the views are still great due to the dunes’ size.

I was highly satisfied with the hotel. Rooms were clean, tidy, and spacious – land seems inexpensive here. The staff were consistently friendly and helpful. They even called to inform me of Mingsha Mountain’s closure due to dusty weather on our first day.

Perhaps due to the off-season, the hotel provided complimentary breakfast for two days, even though our room didn’t include it. Breakfast was delivered to our room, with the option to schedule delivery the day before.

The light breakfast was a welcome change after days of BBQ, lamb chops, and fried chicken.

Transportation

Dunhuang is compact, no more than 10 kilometers across. In 2021, there were only four bus lines.

Parking is plentiful in spring. As a seasonal tourist city, public resources are designed for peak season, leaving ample availability in the off-season. Parking is free at all attractions except Mogao Caves.

Underground parking is rare. Parking fees are very low, capped at 20 yuan per night, with some places charging per entry. Renting a car is highly recommended for freedom and convenience.

Car rental companies are almost exclusively located at the airport, which is conveniently near the train station, allowing for easy pickup and return.

Heed speed limits. It’s easy to speed in this vast, sparsely populated area. Keep your navigation on. The speed limit from the airport to the city is 70 km/h, deceptively low for the wide, open road. There are also 40 km/h zones near schools. The West Line has frequent speed limit changes, so listen to your navigation. Average speed enforcement is in place near Yumenguan.

There are no gas stations on the West Line (to Yumenguan and Yadan), and the round trip is at least 200 kilometers, so fuel up beforehand.

Main Attractions

Dunhuang Museum: Visiting time: 2-3 hours. A 10-minute drive from downtown, with parking available. Free admission, but advance booking and ID card entry are required. The “Bowuguan” (博物官) WeChat mini-program offers audio guides for some artifacts.

Yumenguan Pass: Visiting time: 2-3 hours. The furthest point on the West Line (excluding Yadan), a 2-hour drive, accessible only by self-driving, chartered car, or a local day trip. Purchase tickets on the “You Dunhuang” (游敦煌) WeChat official account. Third-party platforms often bundle tickets with unwanted activities. The West Line is desolate; plan your meals. A restaurant is inside the Yumenguan scenic area, but there are no other dining options en route.

Yangguan Pass: Visiting time: 2-3 hours, potentially longer as it’s expanding. Also on the West Line, you’ll pass it en route to Yumenguan. Buy tickets on the “You Dunhuang” WeChat official account. Many farmhouses surround Yangguan, but their off-season availability is uncertain. A Dicos and possibly another snack place are inside the scenic area.

Mogao Caves: Visiting time: 3-4 hours. East of Dunhuang, near the airport (about a 20-minute drive). Staff will contact you a few days prior to confirm your digital movie viewing time. The visit begins with two digital movies, followed by a bus ride to the cave area. Movie showtimes are fixed, so punctuality is essential. Restaurants are available inside the Mogao Caves area, with additional farmhouse-style options closer to the airport.

Encore Dunhuang (又见敦煌): Visiting time: 1.5 hours. In the off-season, there’s one daily show at 8 PM. The theater is next to Mogao Caves, with its own parking. This performance and Mogao Caves are usually combined. Careful planning is crucial, down to the hour. Calculate your Mogao Caves visit completion time (based on the movie start time), factor in a meal (nearby or in the city), and arrive at the theater before 8 PM. The first hour of Encore Dunhuang is standing-room-only, moving between scenes. Strict security checks prohibit outside food and water.

Mingsha Mountain and Crescent Spring: Visiting time: 3-6 hours (excluding overnight camping). Spend an entire afternoon and stay for sunset. The scenic area is just 3 kilometers from the city. The ticket allows unlimited entries within three days – activate this by scanning your face at a machine near the gate. This makes dining easy, though restaurants are also available inside.

List of All Attractions

Grouped by location for easy planning. Must-see attractions are bolded.

- East Line: Mogao Caves, Encore Dunhuang performance

- West Line: Dunhuang Ancient City Film Base, Western Thousand Buddha Caves, Yangguan Pass, Yumenguan Pass, Yadan Devil City

- South of the City: Mingsha Mountain and Crescent Spring, Leiyin Temple, Dunhuang Grand Ceremony performance

- Guazhou Line: Yulin Caves, Suoyang City

- Other in the City: Dunhuang Museum, White Horse Pagoda, Shazhou Ancient City, Silk Road Flower Rain performance

The West Line is a single road, listed from nearest to furthest. You can’t cover all five locations in one day; skip 2-3.

The Guazhou Line requires a trip to Guazhou County (part of Dunhuang City). The Yulin Caves are reportedly worthwhile, managed by the same unit as Mogao Caves, and feature many exquisite works.

Other city attractions can fill itinerary gaps.

Local small parks and minor attractions are excluded.

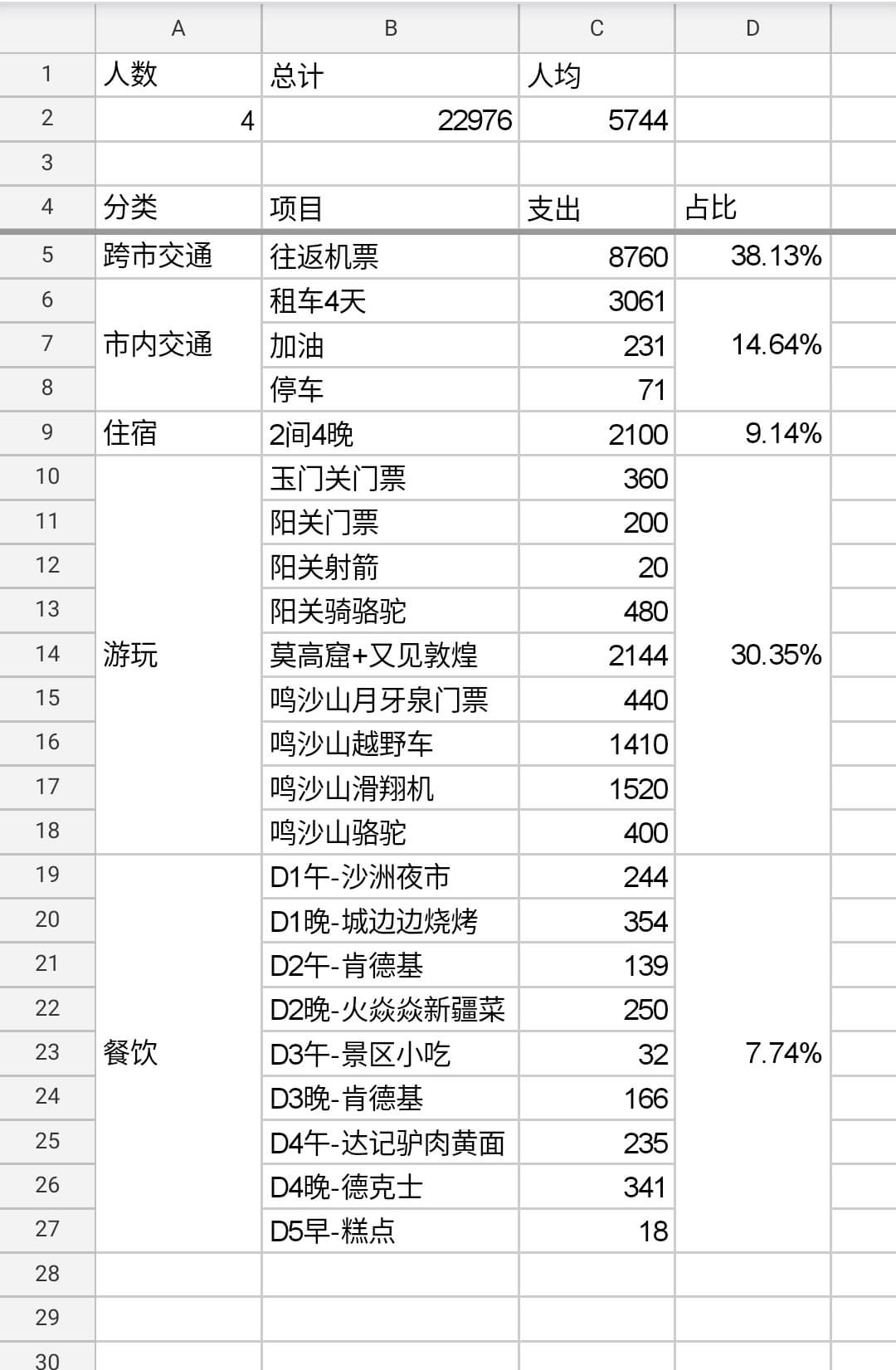

Expenses

Hotels and transportation are very inexpensive in the off-season. Dining costs are normal, and even fruit prices are comparable to Hangzhou. Our primary expenses were airfare and recreational activities.

Other People’s Guides or Travelogues

Here are some other guides and travelogues I found useful:

- Comprehensive travelogue: https://www.mafengwo.cn/i/10927558.html

- Comprehensive travelogue: http://www.mafengwo.cn/i/10546594.html

- West Line travelogue: http://www.mafengwo.cn/i/16989550.html

- Dunhuang’s three major performances: https://www.mafengwo.cn/gonglve/ziyouxing/14655.html

Behind the Scenes

I was in charge of planning this entire trip, and everyone I traveled with was really happy with the itinerary I put together.

Honestly, there’s a simple, repeatable process for planning a trip. Once you string all the key elements together in the right sequence, the itinerary practically writes itself.

For the full breakdown, you can check out this article: A Step-by-Step Guide to Travel Planning.