I’ve always been skeptical about annualized returns. Do they really tell us anything useful when picking a fund? Sure, it seems objective to put everything on an annual basis so you can compare funds and different investment periods. But it mixes in other stuff, so it doesn’t really show how profitable the fund is or what you actually earned.

Let’s use an extreme hypothetical example. Suppose we both invest in the same fund:

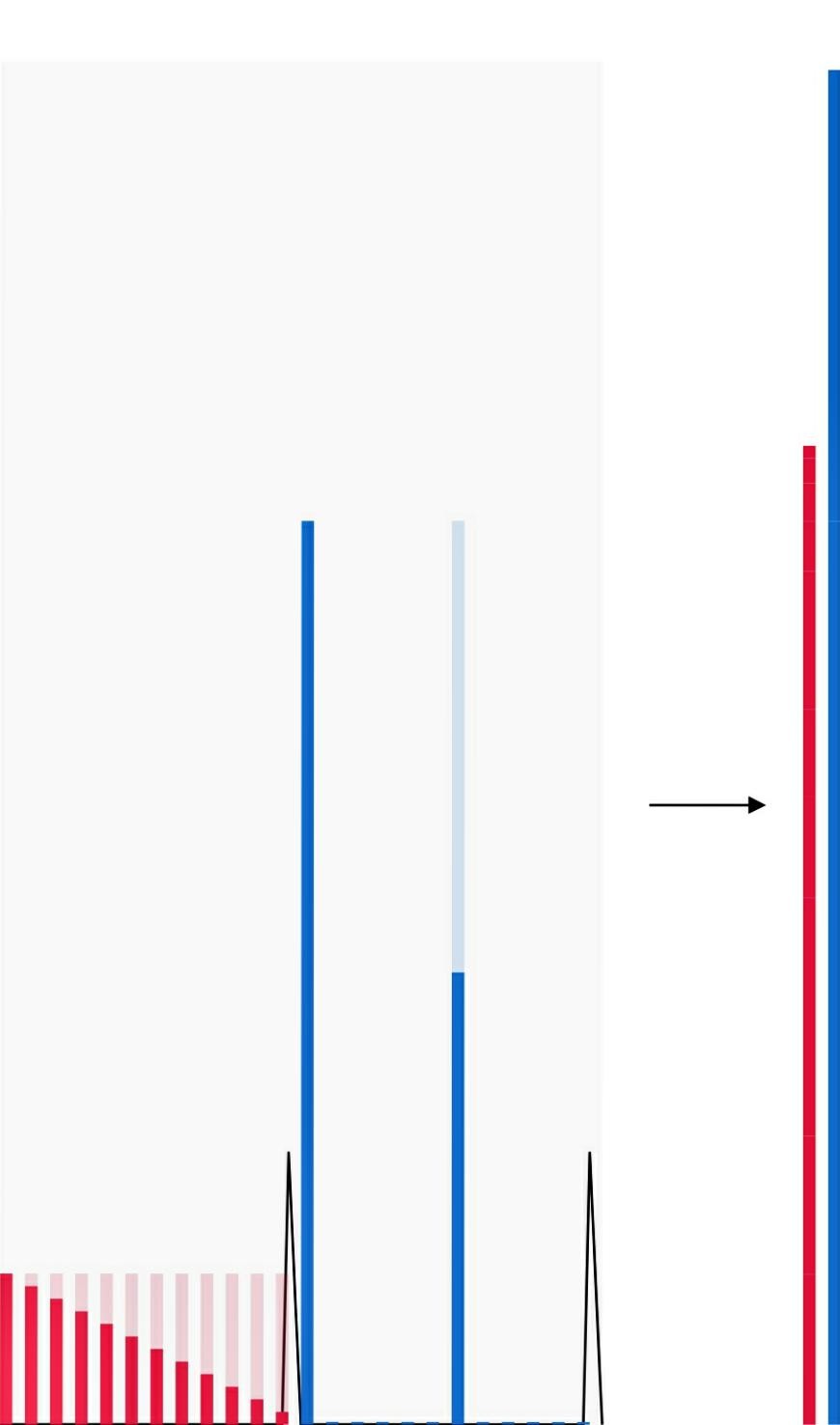

Look at the left half first. There are 24 columns, each representing a month, for a total of 2 consecutive years. The black line shows the net asset value (NAV) of the fund. This fund is extreme; the NAV stays flat all year, except on December 31st, when it suddenly doubles, and then drops back down on January 1st of the following year.

Let’s look at your actual investment and return first. You invested in the first year. The light red columns are your actual investments, 120 yuan on the 1st of each month. Your total investment was 120 x 12 = 1440 yuan. Since the NAV was flat, you bought the same number of shares each month. You cashed out at the December 31st price. Ignoring fees, you got back 2880 yuan, for an actual return of 1440 yuan and an actual rate of return of 100%.

Now for your annualized return. To calculate that, we have to annualize each investment. If you held it for less than a year, we discount the amount. We’ll call this the “annualized investment,” shown by the dark red columns. The first month’s annualized investment is the same as the actual, 120 yuan. The second month is discounted. Only 11 out of 12 months counted. Assuming each month has the same number of days, the annualized investment is 110 yuan. It’s the same deal for the following months, going down by 10 yuan each time. Your total annualized investment is 120 + 110 + 100 + … + 10 = 780. Basically, investing 120 yuan each month is the same as putting in 780 yuan all at once in the first month. Your annualized rate of return is the 1440 yuan return / 780 yuan annualized investment = 184.6%.

Now my turn. I invested in the second year, twice, on January 1st and July 1st, putting in 720 yuan each time, for a total of 1440 yuan. I cashed out at the same time as you, getting 2880 yuan, with an actual return of 1440 yuan and an actual rate of return of 100%.

My annualized return is different. The January investment is the same as the actual, 720 yuan. The July one is only for half the time, so it’s discounted by half, to 360 yuan. My total annualized investment is 720 + 360 = 1080 yuan. My annualized rate of return is 1440 / 1080 = 133.3%.

We got the same actual return, the same 100% rate of return, and over the same time. But our total annualized investment is different, as you can see on the right side of the figure. So your annualized return is 184.6%, while mine is 133.3%.

See how messed up this annualized return thing is? It doesn’t just show how well the fund itself did, but also how you invested. So what’s it even comparing?

And here’s another thing: with these two ways of investing, the total money we end up with is actually different. We put in the same amount over the same time and got the same return in the fund, but there’s also the outside of the fund. You had your money tied up for less time, so you had more time to earn interest from bank products. I had mine tied up earlier, half at the start, and all of it by the middle of the year. I missed out on a lot more interest. If we compare how much these two piles of money grew after a year, you’d have more.

A high annualized return really means two things: less time with your money tied up, and higher returns. Our actual returns were the same, but the annualized returns are different. The main reason is the difference in how long the money was tied up. But how big of a difference? Those numbers, 184.6% and 133.3%, don’t tell you anything, just that the higher one had less time tied up.

Back to the example, how do you get the highest annualized return? Dump all your money in on December 30th and pull it out on December 31st. So if you’re chasing the ultimate annualized return, you end up like a day trader, catching a quick spike and bailing out.

That’s the opposite of what sensible investing is supposed to be. So why not just focus on how fast your assets are growing, the compound annual growth rate (CAGR)? How much did you put in, how long was it in, how much did the fund make when you cashed out, and how much interest did you make on your idle cash? Use that to figure out how fast your money grew.

Calculation spreadsheet: https://qvokpfxqsh.feishu.cn/wiki/WMurwbQq6i6SYakjbWAccp8JnHf