I recently visited the Zhejiang Museum of Natural History’s Anji branch, a place I’d been meaning to check out. It’s located in Anji County, Huzhou, about an hour’s drive from Hangzhou.

I opted for the afternoon session (12 PM - 4 PM), which is longer. But for a museum enthusiast like myself, time flies. Four hours for six halls means prioritizing – you can’t see everything in detail.

The recommended order is: Geology, Behring, Ocean, Natural Art, Dinosaur, and Ecology. Being my first visit, I moved quickly, took fewer pictures, and focused on the exhibit texts.

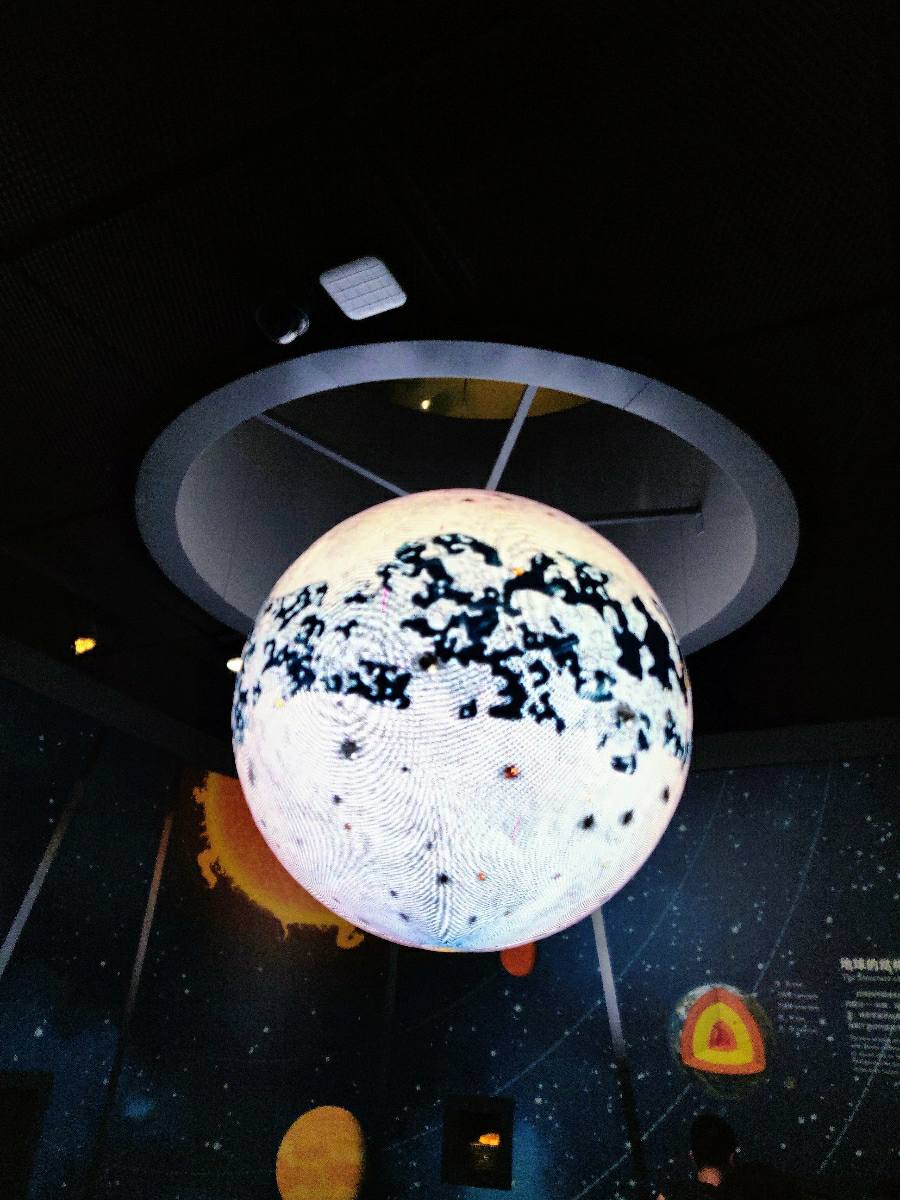

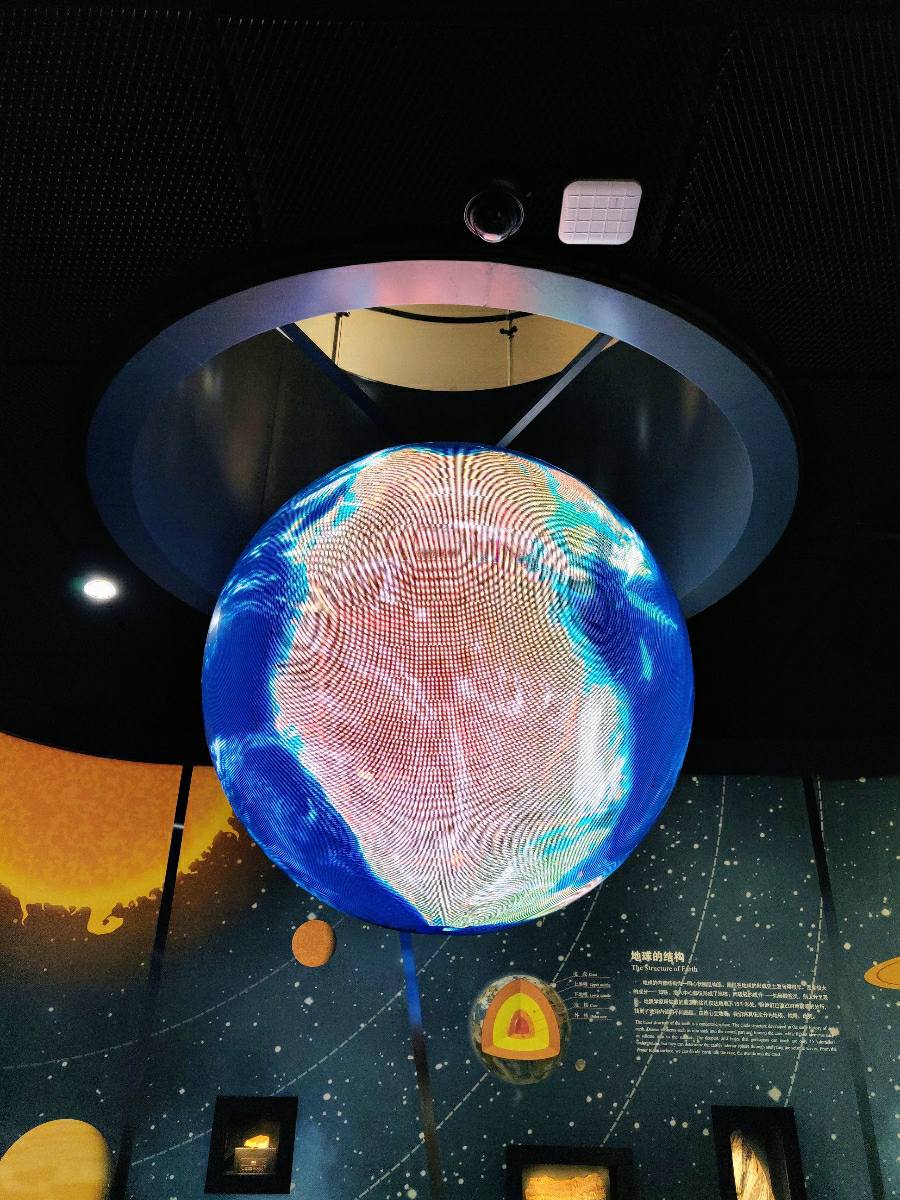

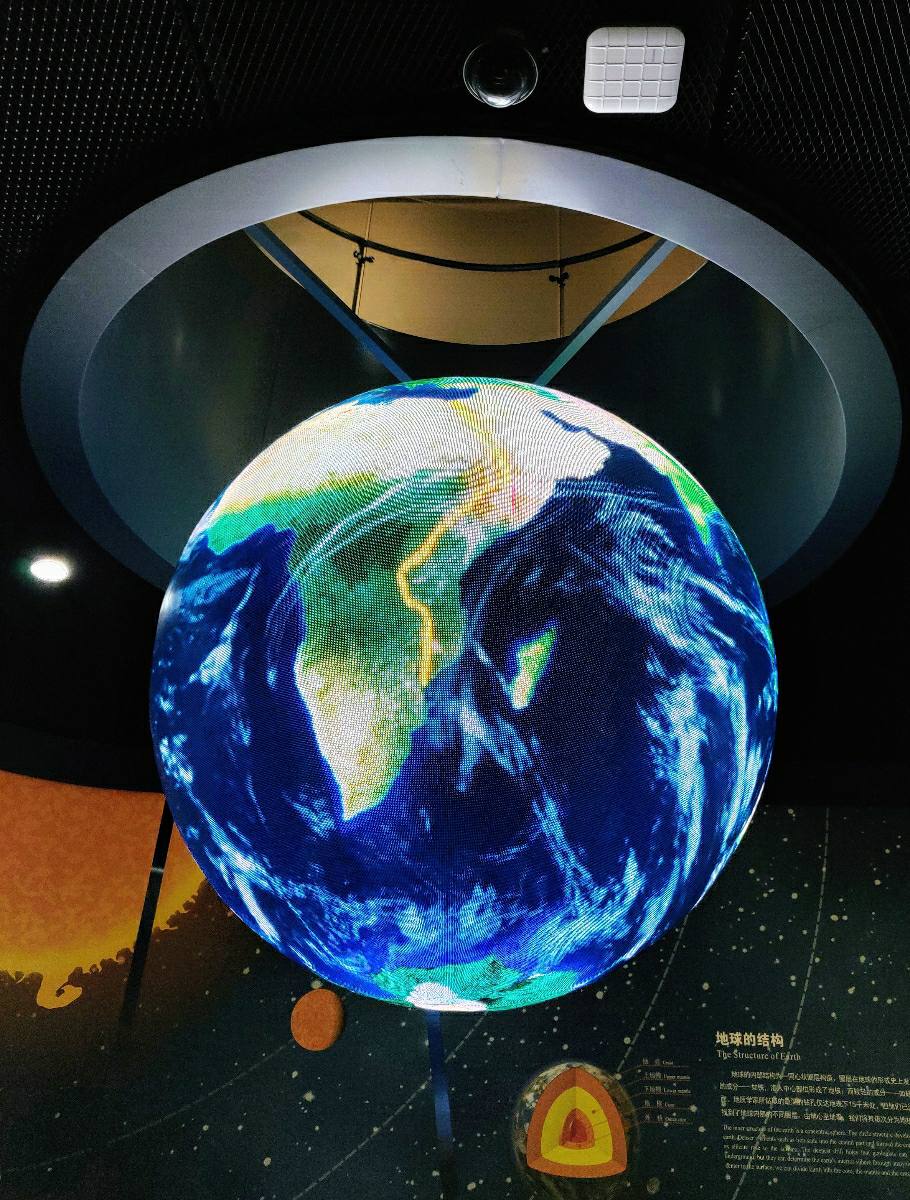

Geology Hall

The introduction is striking: a spherical screen displays Earth’s 4.6-billion-year evolution. Surrounding it, small exhibits showcase rocks and meteorites – granite, metamorphic, sedimentary, even meteorites from Mars and the Moon.

If you’re familiar with Earth’s history, the intro’s brilliance is clear: 4.6 billion years of dramatic change, with life somehow emerging in a volatile environment. From there, the epic of life’s evolution unfolds in the following six halls.

The introductory video is surprisingly detailed, covering major geological events.

Snowball Earth: A massive global ice age. Expanding glaciers reflected sunlight, reducing heat absorption and creating a feedback loop that froze the entire planet. The photo depicts volcanic activity, caused by crustal movement, which reversed this process.

Snowball Earth

Pangaea: The second instance of all continental plates merging into a supercontinent. Pangaea’s center, far from oceans, became vast Gobi deserts – the video is quite realistic. Pangaea eventually broke apart, forming today’s continents and oceans.

Pangaea

East African Rift Valley: Crustal movement is separating the African and Arabian plates, creating a rift valley spanning East Africa. Notably, our human ancestors would eventually emerge from this region.

East African Rift Valley

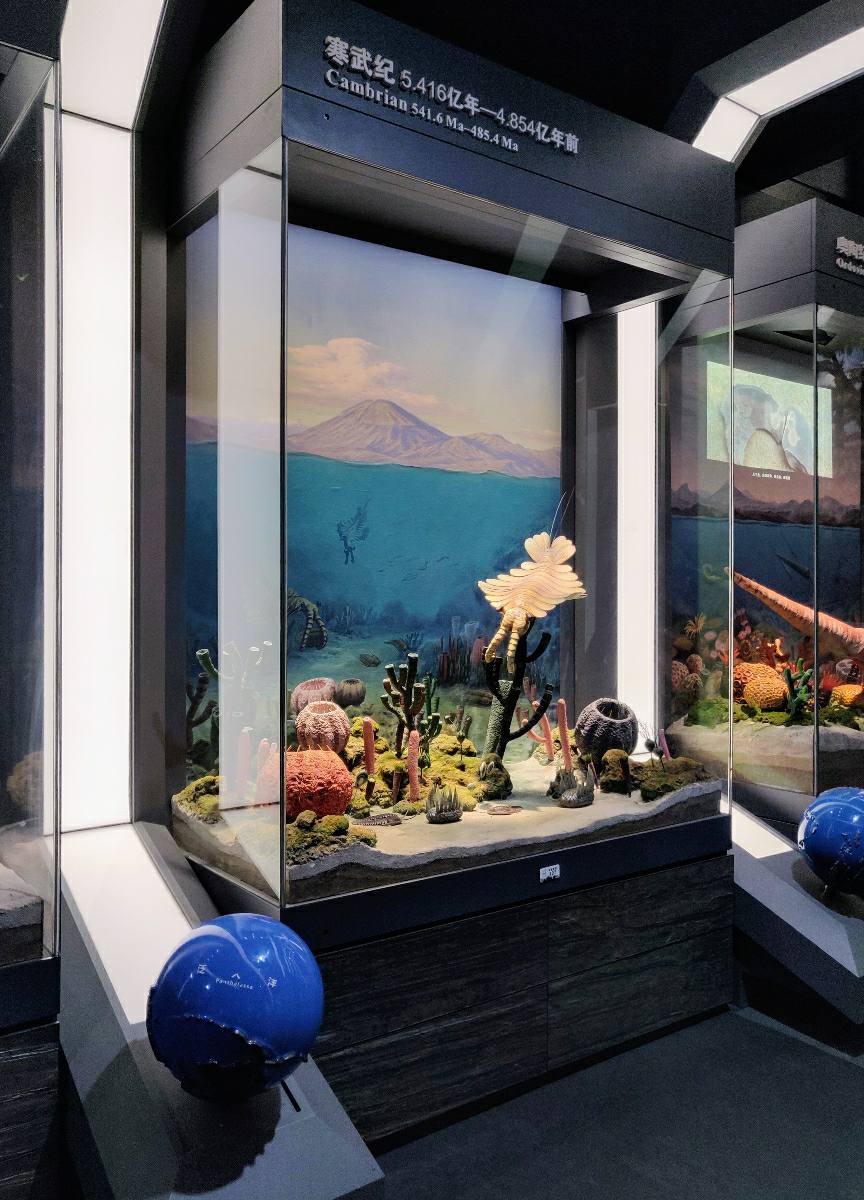

The Geology Hall’s central theme is the geological time scale. Everything pre-Cambrian is grouped as Precambrian. Subsequent periods each have displays of equal size and format, showcasing typical life and environments.

I suggest initially skipping the displays on the opposite side of the corridor. Focus on the main displays along one side – the hall’s core. Familiarity with evolution and taxonomy enhances the “epic of life” experience: primordial life in the oceans, the Cambrian explosion, Devonian plants conquering land, amphibians emerging, Mesozoic reptile dominance, and mammal takeover after the dinosaur extinction. It’s a whirlwind tour of life’s history.

Cambrian Display

Don’t overlook the small globes beside the displays. Each shows the continental distribution of that period. Unfortunately, they’re positioned too low; even for children, the ocean dominates the view. You need to crouch to see the landmasses, discouraging interaction.

Cretaceous Display

The displays are exceptionally well-crafted. Plant specialists might spot small yellow flowers from the Cretaceous onward, aligning with the prevailing theory of angiosperm (flowering plant) origin in that period.

Cretaceous Display - Small Yellow Flowers

After experiencing the main timeline, return to the hall entrance and explore the other side. As the Zhejiang Museum of Natural History, the geology section highlights Zhejiang’s history and contributions.

Zhejiang formed from the merging of two landmasses. Check your map app’s terrain view to see the rift valley in western Zhejiang’s hills.

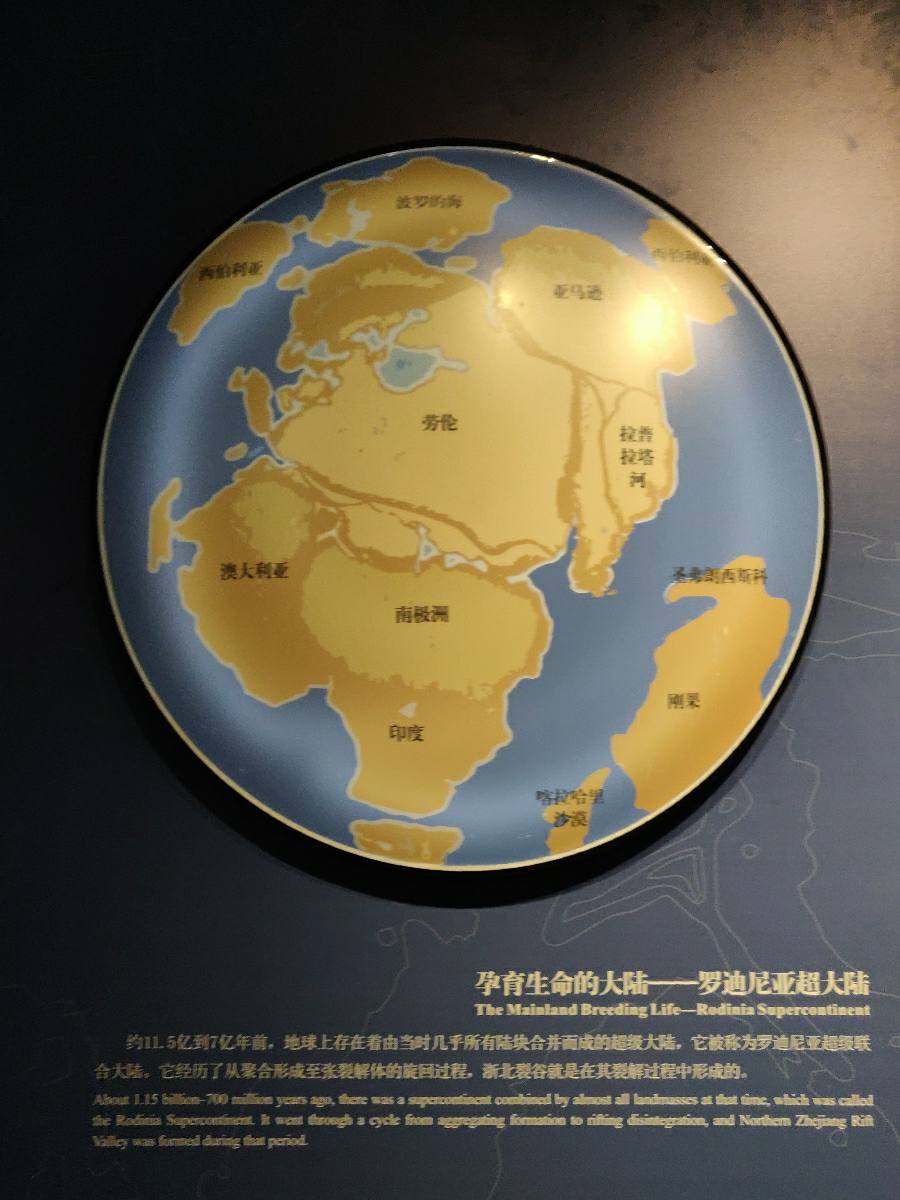

Rodinia: A supercontinent, like Pangaea, where landmasses were joined. Rodinia existed much earlier than Pangaea.

Rodinia

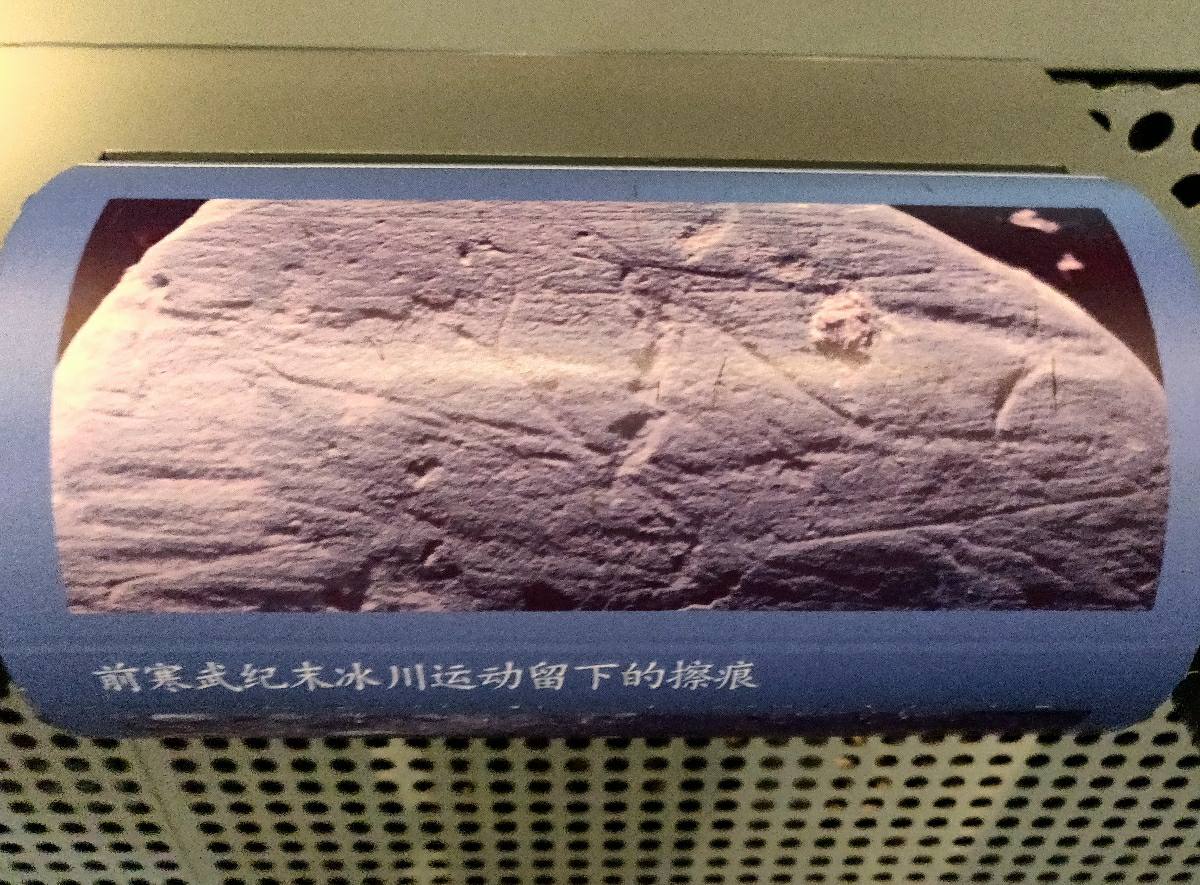

Evidence of Glacial Movement

Remember Snowball Earth? The discovery of tillite was key to proving such extensive glaciation. The principle resembles these scratches, but is more definitive.

Tillite forms from slow-moving glaciers. The immense force scrapes up various rocks, incorporates them into the glacier, and crushes them. Disparate rocks become tightly compacted. When unearthed, geologists recognize glacial action as the only explanation. Tillite’s global distribution proves past global glaciation.

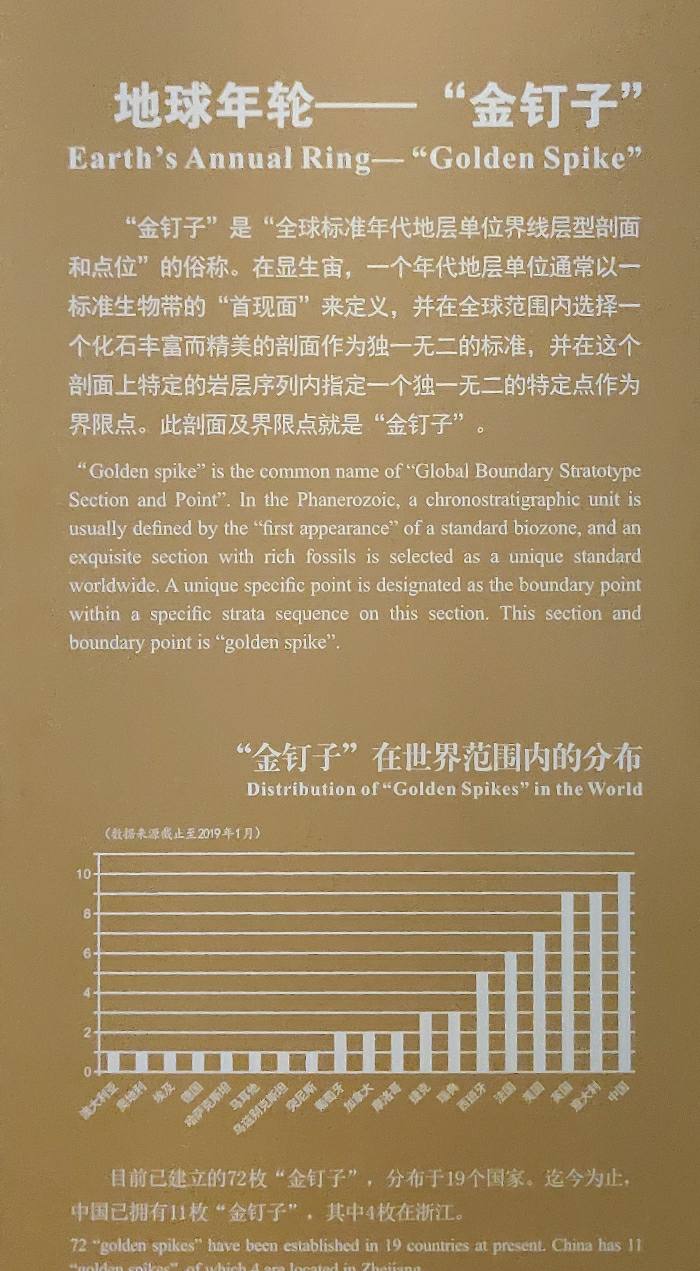

Golden Spike

The display’s explanation is concise. Let me expand on Golden Spikes. They’re essentially standards for demarcating geological ages.

Earth’s 4.6-billion-year history requires division into periods, similar to China’s dynasties. Given the vast timescale, multiple divisions are needed. The Qing Dynasty is subdivided into Qianlong, Jiaqing, and Daoguang. Geology uses six levels, from largest to smallest. The most familiar are:

- Archean

- Proterozoic

- Paleozoic (The names of first four periods come from British locations where corresponding strata were initially discovered)

- Cambrian (Explosion of life, appearance of mollusks and arthropods)

- Ordovician (Appearance of chordates)

- Silurian

- Devonian (Fish dominated)

- Carboniferous (Plants with lignin grew tall. Bacteria and fungi to decompose it hadn’t evolved, so buried wood formed thick coal seams)

- Permian

- Mesozoic

- Triassic (Dinosaurs emerged)

- Jurassic

- Cretaceous (Dinosaur extinction)

- Cenozoic (Mammals rose)

- Tertiary

- Quaternary

So, what are Golden Spikes? They’re based on fossils of specific, representative species. These species, distinct from predecessors and reflecting major environmental shifts, mark the boundaries between geological ages. Organisms are markers; they divide geological time.

The hall features numerous interactive displays. If interested, you can explore them for a deeper understanding of the hall’s theme.

Coal Formation

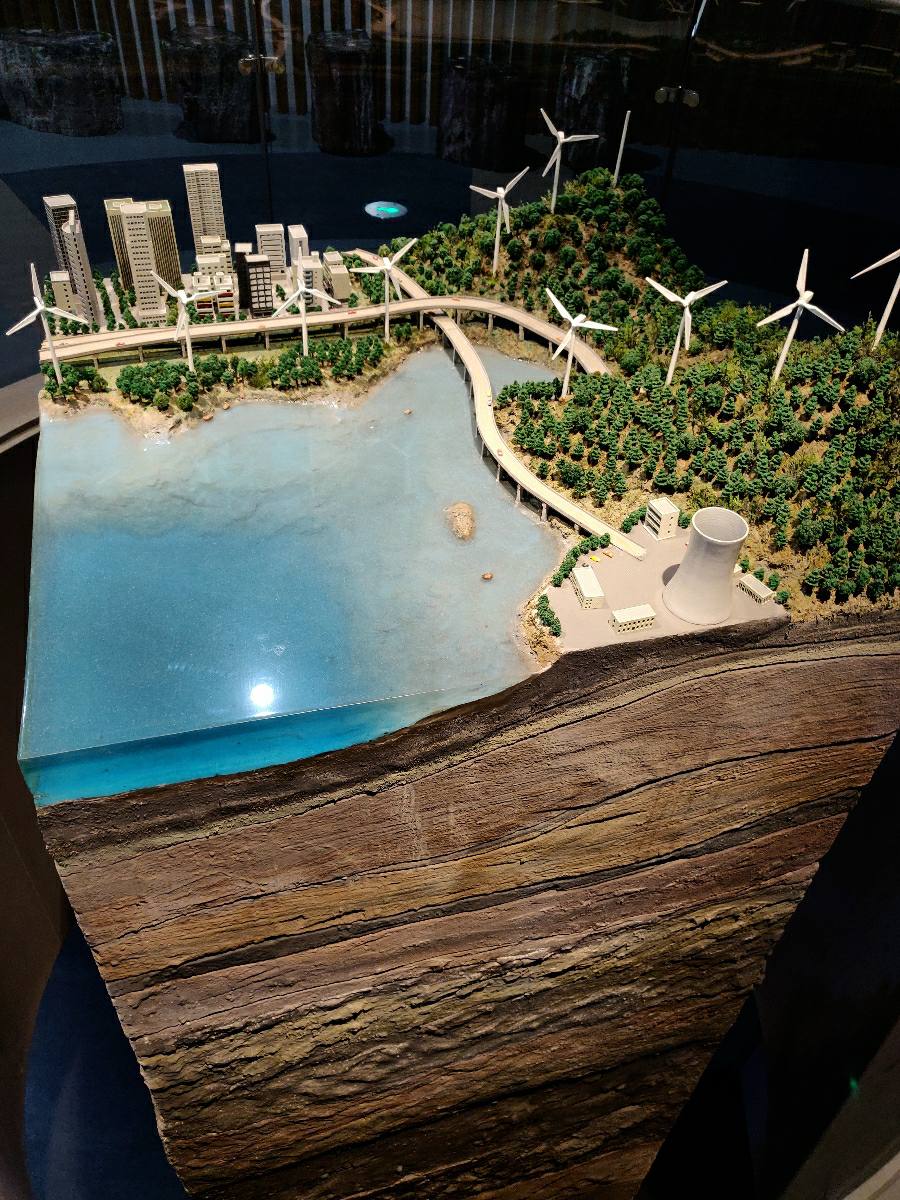

A somewhat overlooked installation on the second floor provides a fitting conclusion to the Geology Hall, echoing the opening’s depiction of Earth’s evolution. Beneath us lies the profound history of Earth and life. On a geological timescale, what mark will our modern civilization leave? What should it leave?

Behring Hall

This hall is named after Kenneth Behring, a businessman and philanthropist who donated numerous wildlife specimens, primarily displayed here. It’s essentially the terrestrial animal hall.

1st Floor: Terrestrial Animals and Environments

The first floor focuses on terrestrial animals from different continents, showcasing representative species from Africa, North America, and Australia. Africa has the largest exhibit, representing the hall’s biodiversity centerpiece.

This scene is vast; I only captured a portion. The specimens’ lifelike poses and movements evoke a Serengeti National Park experience.

Perhaps due to my familiarity with nature documentaries, the animal specimens didn’t hold my full attention. I took fewer general photos, focusing instead on the text explanations and the animals’ survival strategies.

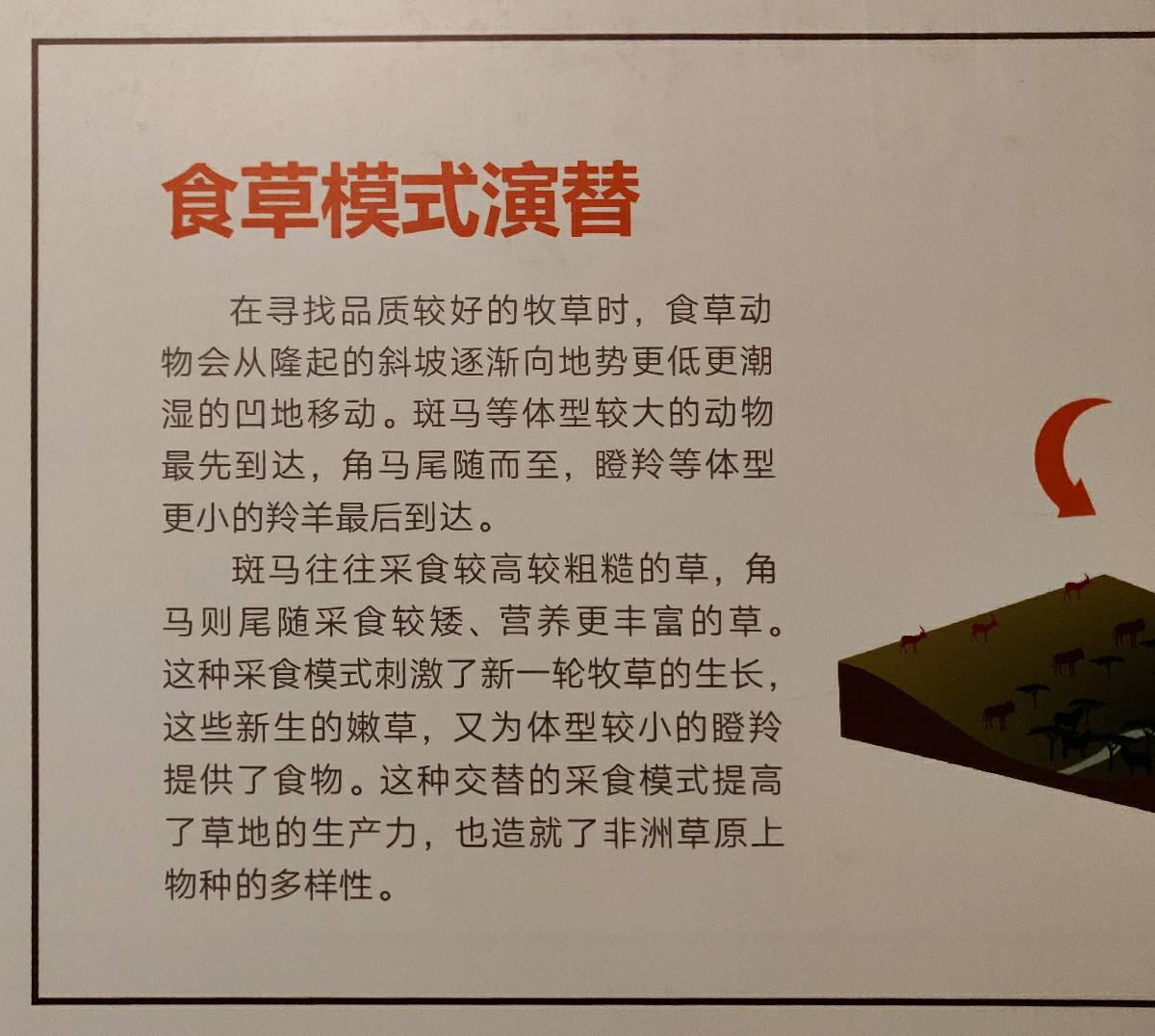

How different African savanna herbivores utilize resources, partitioning niches to avoid competition and maximize resource use.

A must-take photo: African large animal group portrait.

Warthog Specimen

The specimens’ postures have a scientific basis. A warthog raising its tail signals to predators: “I’m healthy and strong; you likely can’t catch me. Consider another target.”

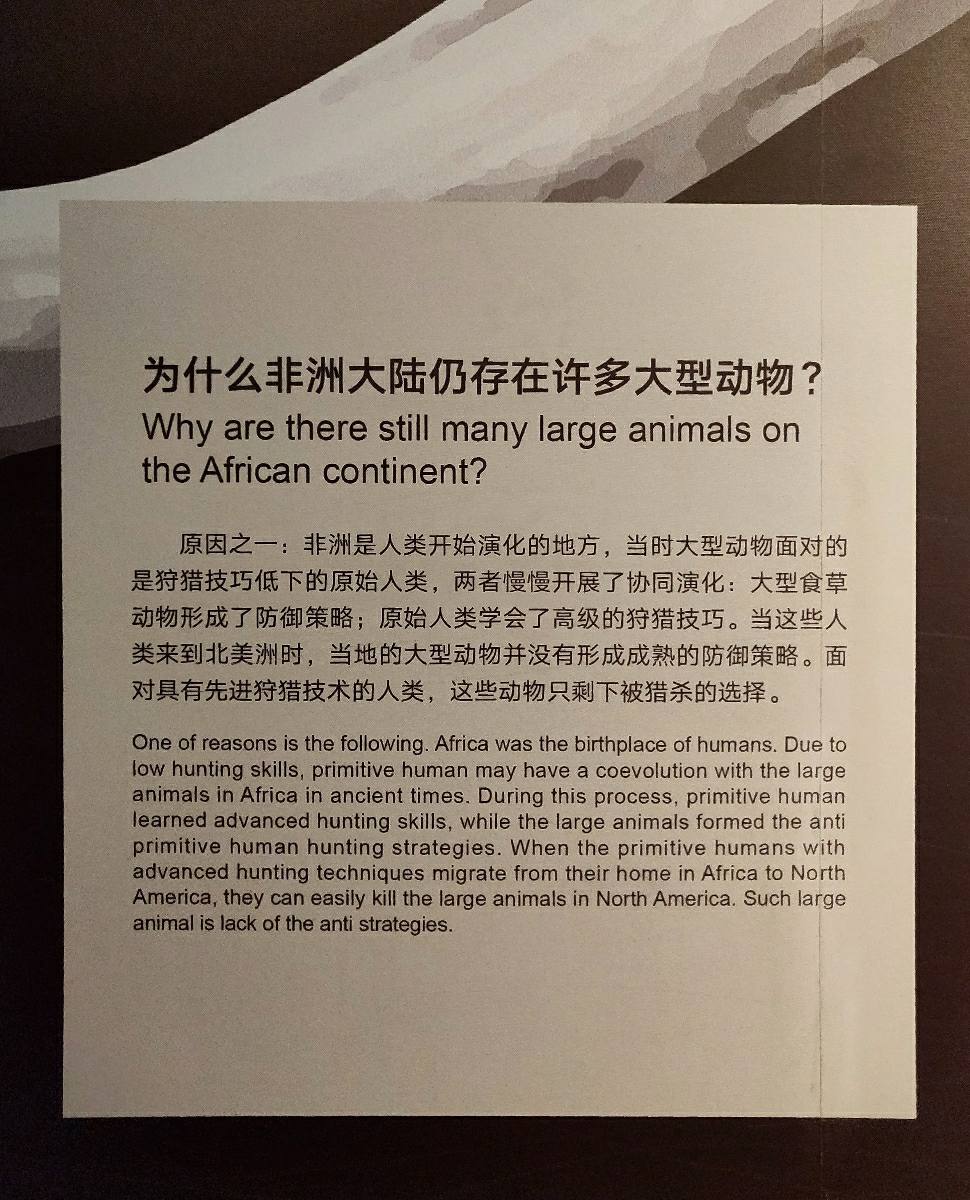

A pertinent question, aiding understanding of natural selection and the predator-prey arms race.

While less diverse in large animals than Africa, North America and Australia are key to this hall’s species evolution exhibits.

Why are species on different continents so distinct?

Mammalian evolution has three stages:

- Prototheria: The most primitive. Like the platypus, they lay eggs and secrete milk through their skin – unlike most mammals, but they’re classified as such.

- Metatheria: Marsupials like kangaroos, Tasmanian wolves, and koalas. Born underdeveloped, they require a pouch to complete development.

- Eutheria: Placental mammals like mice, antelopes, and gorillas. A newborn antelope can stand and run soon after birth, fully developed at birth.

Placental reproduction clearly offers better offspring protection. Combined with other advantages, it led to placental mammals outcompeting the other two groups globally. However, Australia’s early isolation by oceans, before placental mammals appeared, allowed marsupials to dominate, while they were replaced elsewhere.

South America also retains many marsupials. The Bering Strait land bridge provided a narrow passage from Eurasia and Africa to North America. The Isthmus of Panama later reconnected, allowing placental mammals into South America. Their late arrival explains the survival of South American marsupials, which even spread back into North America.

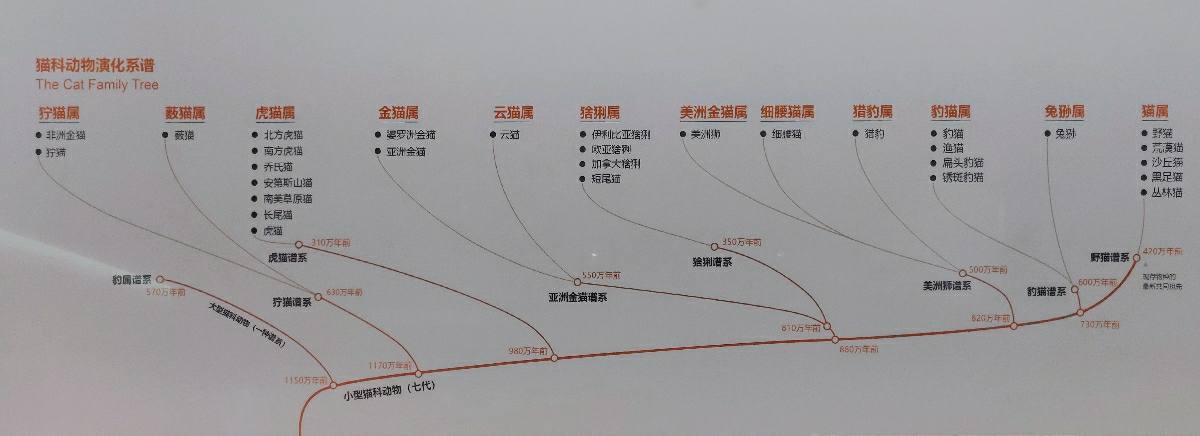

Cats, highly efficient predators, occupy the top of the food chain in most terrestrial environments. The museum dedicates a significant section to them.

Cat Family Tree

A bit of a feline tongue-twister: Lions are Pantherinae; cheetahs are Felinae. Cougars are Felinae; jaguars are Pantherinae.

Cat Family’s First Great Migration

In short: Cats originated in Southeast Asia. Their unique lifestyle led to remarkable dispersal. Adult cats must leave their families and establish new territories. Their large territories necessitate long migrations, leading to rapid occupation of available land.

Cat Family’s Second Great Migration

Both migrations resulted from falling sea levels, creating new land bridges. Comparing this with the cat family tree, small cats initially spread to all continents (except Australia), followed by large cats from Eurasia and North America expanding into Africa and South America.

2nd Floor: Animal Evolution

The second floor highlights species evolution, focusing on adaptations to environments. For instance, the entrance introduces convergent evolution, where different species evolve similar features for the same function. Wings are a prime example: birds, bats (mammals), and insects have evolved different wing types, all achieving flight.

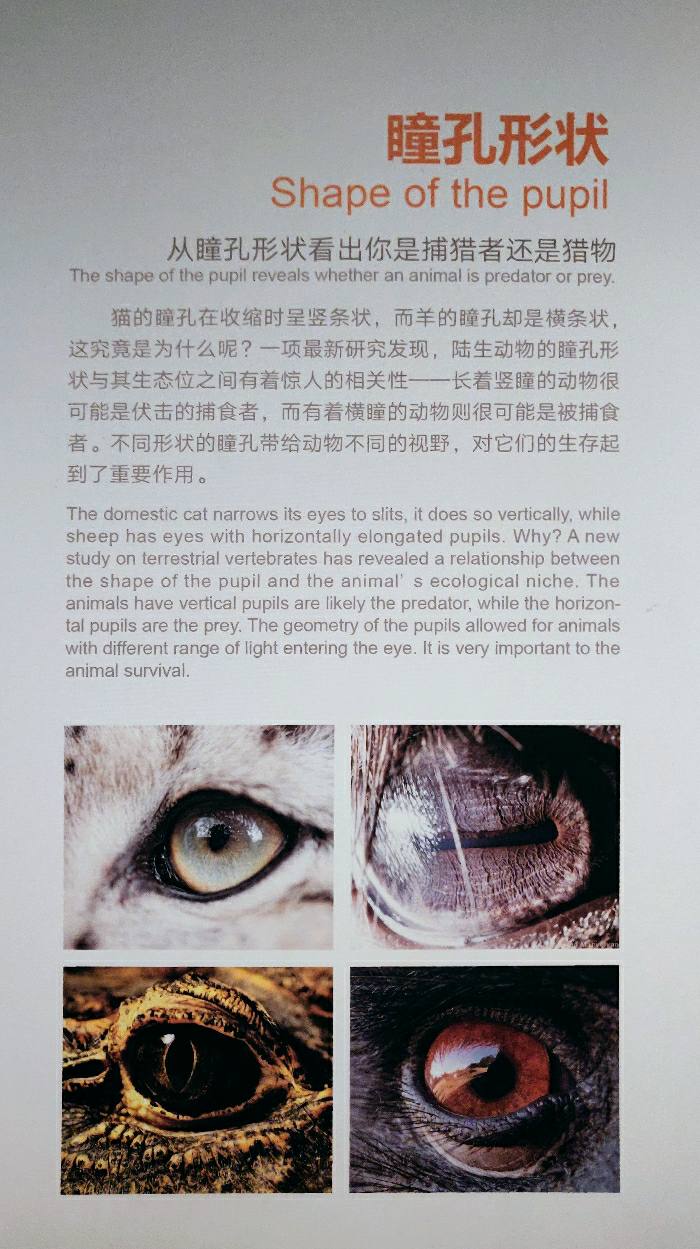

Sideways or forward-facing eyes provide different advantages.

Pupil shape, like eye position, relates to vigilance or hunting.

Advantages of different pupil shapes (zoom may be needed).

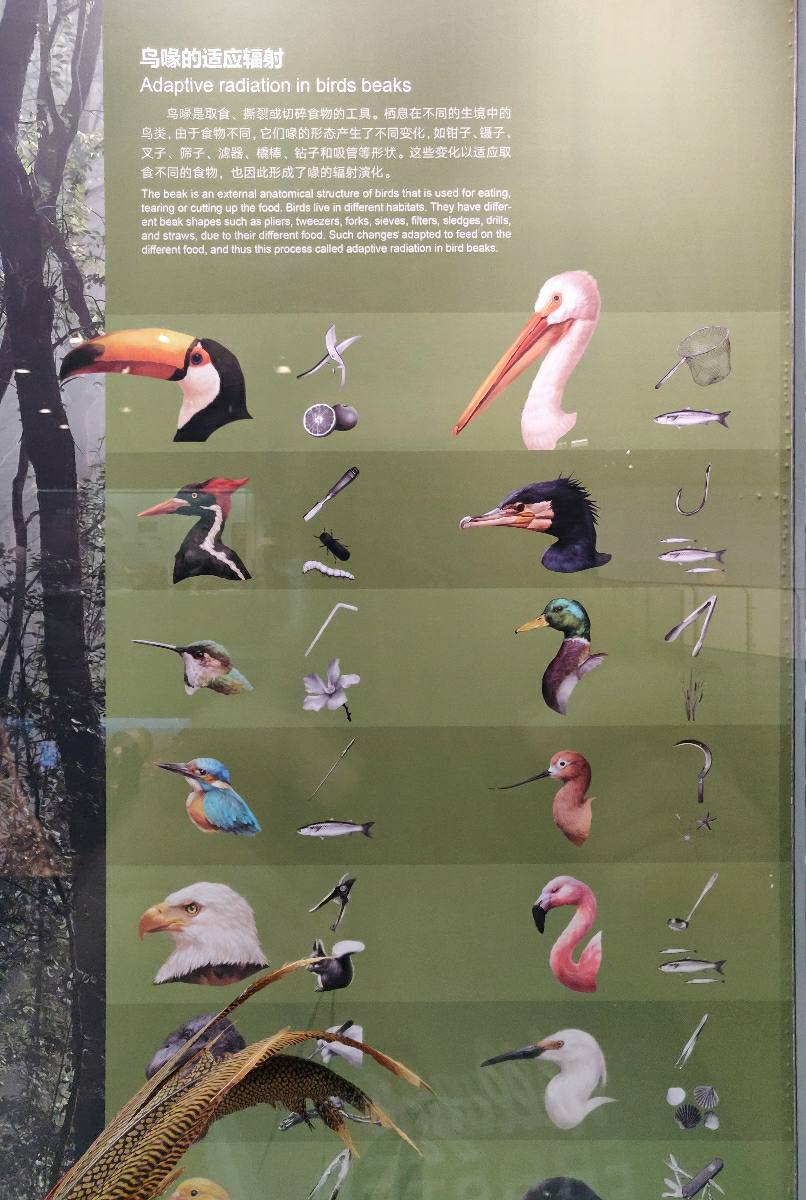

The bird section is a highlight, visually comparing bird beaks to human tools to illustrate diet and feeding. I found the pelican amusing – a living net. However, I question the flamingo’s depiction, as they don’t primarily eat fish. This might be an inaccuracy.

Bird Beak Shapes and Functions

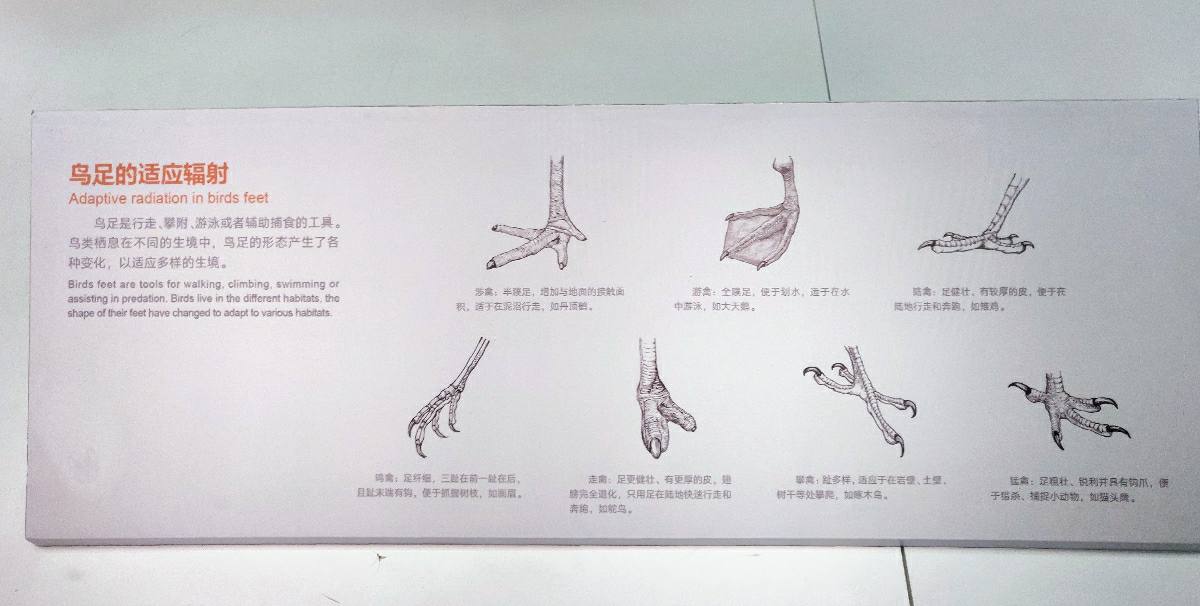

The next display continues, adding bird feet. You can deduce a bird’s diet and habitat from the beak and foot combination. Birds are categorized into seven groups based on feet:

- Wading birds: Shallow-water dwellers, non-swimmers, relying on water for food. Long necks and legs. Small webs between toes aid traction on mudflats. Example: Cranes.

- Waterfowl: Aquatic birds, capable of floating and swimming, some diving. Fully webbed toes act as paddles. Example: Ducks.

- Landfowl: Ground-dwelling, flight is secondary. Leg strength supports walking. Example: Chickens.

- Songbirds: Branch dwellers, small, known for singing and nest-building. Thin legs grip branches naturally. Example: Magpies.

- Running birds: Ground-dwelling, large, flightless. Strong legs, enhanced running ability. Example: Ostriches.

- Climbing birds: Inhabit vertical spaces (tree trunks, cliffs). Two toes forward, two backward, for stability. Example: Parrots.

- Birds of prey: Aerial hunters. Sharp, hooked claws grasp prey. Example: Eagles.

Classification of Bird Feet

Combination of Bird Beaks and Feet

For comic relief: Shoebill

Following the bird section, examples of animal appearance and behavior adapting to the environment are presented.

The Same Species in Different Environments

Mimicry, such an ingenious behavior, deserves more detailed explanation.

Exit Corridor

Descending from the second floor, you enter the exit corridor. Here, you’ll find a biography of Mr. Behring and his contributions to science education. One side features a sobering timeline of animal extinctions since the 17th century, culminating in the northern white rhino, which went extinct in the wild in 2018.

Animal Extinction Timeline

Northern White Rhino Extinct in the Wild

Public attention often centers on animals, particularly large ones. However, since industrialization, the number of extinct small mammals, reptiles, insects, marine animals, and plants is far greater. The full timeline is truly disheartening.

Ocean Hall

I spent 2.5 hours in the first two halls and started to lose steam by the Ocean Hall, taking almost no photos.

Honestly, the Ocean Hall isn’t as impressive as the first two. The layout is confusing. You ascend a spiral ramp to the 2nd floor, descend another to the 1st, and then find yourself disoriented, forced to explore radially outwards. The hall’s narrative also feels disjointed, lacking a clear storyline.

The ascending spiral has its moments, captured in this short video: 【浙江省自然博物馆安吉馆-海洋馆入口-哔哩哔哩】. Ocean-themed photography lines one side of the corridor, the vibrant colors of the marine world creating a strong visual impact.

The 2nd-floor section follows an ecosystem approach, showcasing environments like rocky shores, estuaries, mangroves, kelp forests, and coral reefs. The deep sea should be included, but it’s understandably absent due to our limited knowledge. The exhibits are mostly text and image-based, lacking specimens and dioramas due to space constraints.

On the descending spiral, several large marine animal specimens (or perhaps models) are suspended overhead.

Reaching the 1st floor, you enter an enclosed area. Small live aquariums are interspersed with display boards, featuring common marine life such as fish and jellyfish.

Branching out from this central area, you’ll find exhibits on marine mammals, cephalopods, polar ecosystems, deep-sea exploration, the marine economy, and marine conservation – a somewhat scattered arrangement.

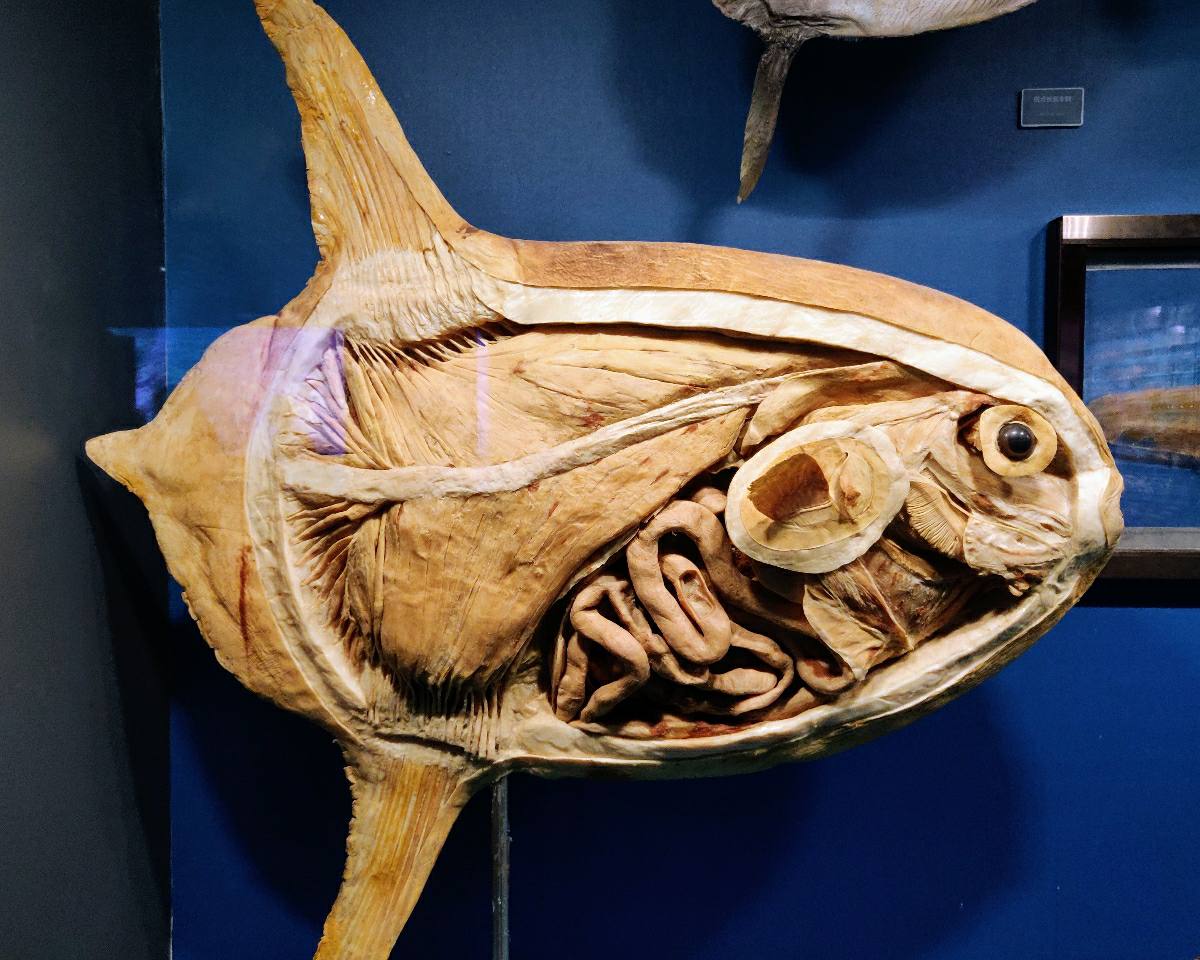

Ocean Sunfish Internal Structure

I quickly moved on after this.

Natural Art Hall

This hall was impressive, but I didn’t linger, eager to reach the Dinosaur Hall.

The Natural Art Hall’s theme is simple: no geological or biological expertise needed. Just bring your eyes and appreciate nature’s beauty directly – a quick visit.

1st Floor: The Beauty of Life

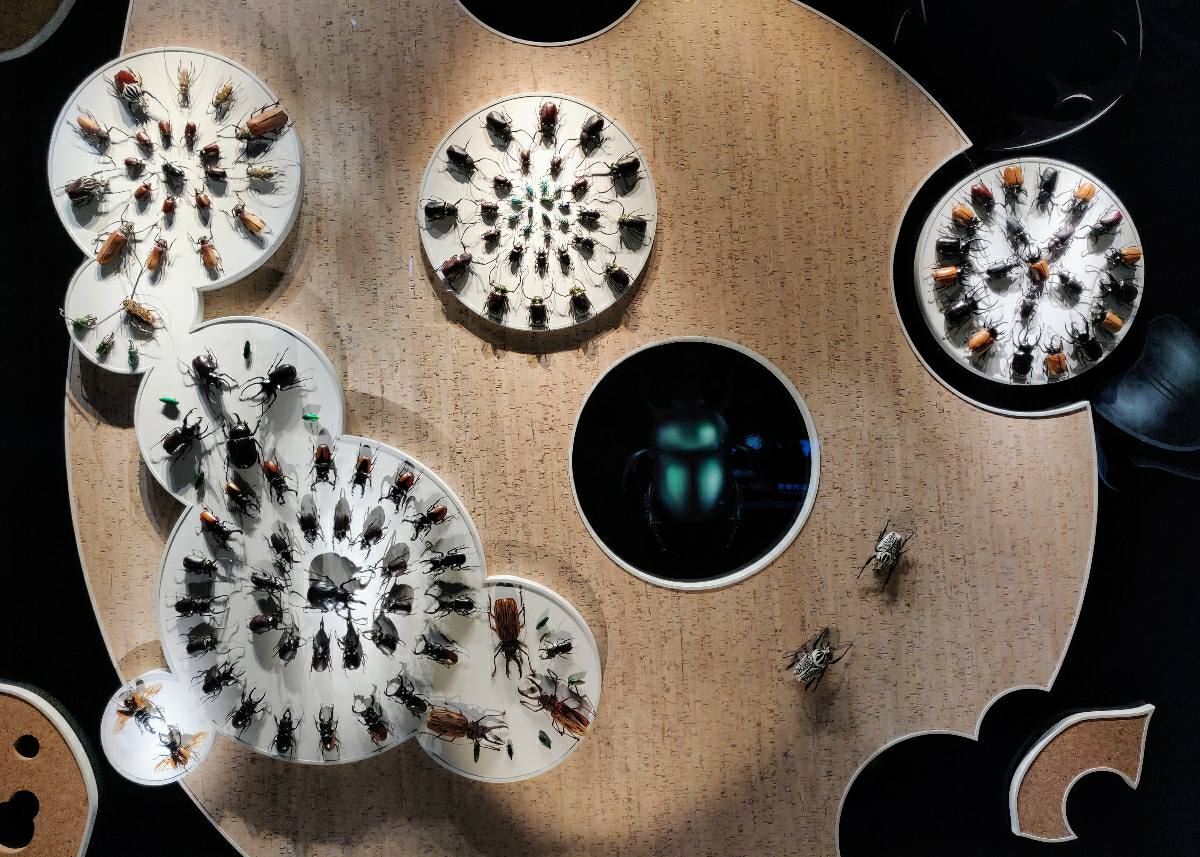

The 1st floor celebrates the beauty of life. Leaves, wood grains, butterflies, beetles, shells, feathers, and more are displayed artistically. These natural creations are stunning individually, and their collective display is breathtaking.

Colorful butterfly ornaments

Beetle display case

Beetles in nature are even more vibrant, many with an iridescent sheen. I suspect limitations in specimen preparation and collection prevented showcasing their full splendor. Beetles belong to Coleoptera, the most diverse order of insects, and indeed, of all animals. This species richness results in a stunning variety of appearances.

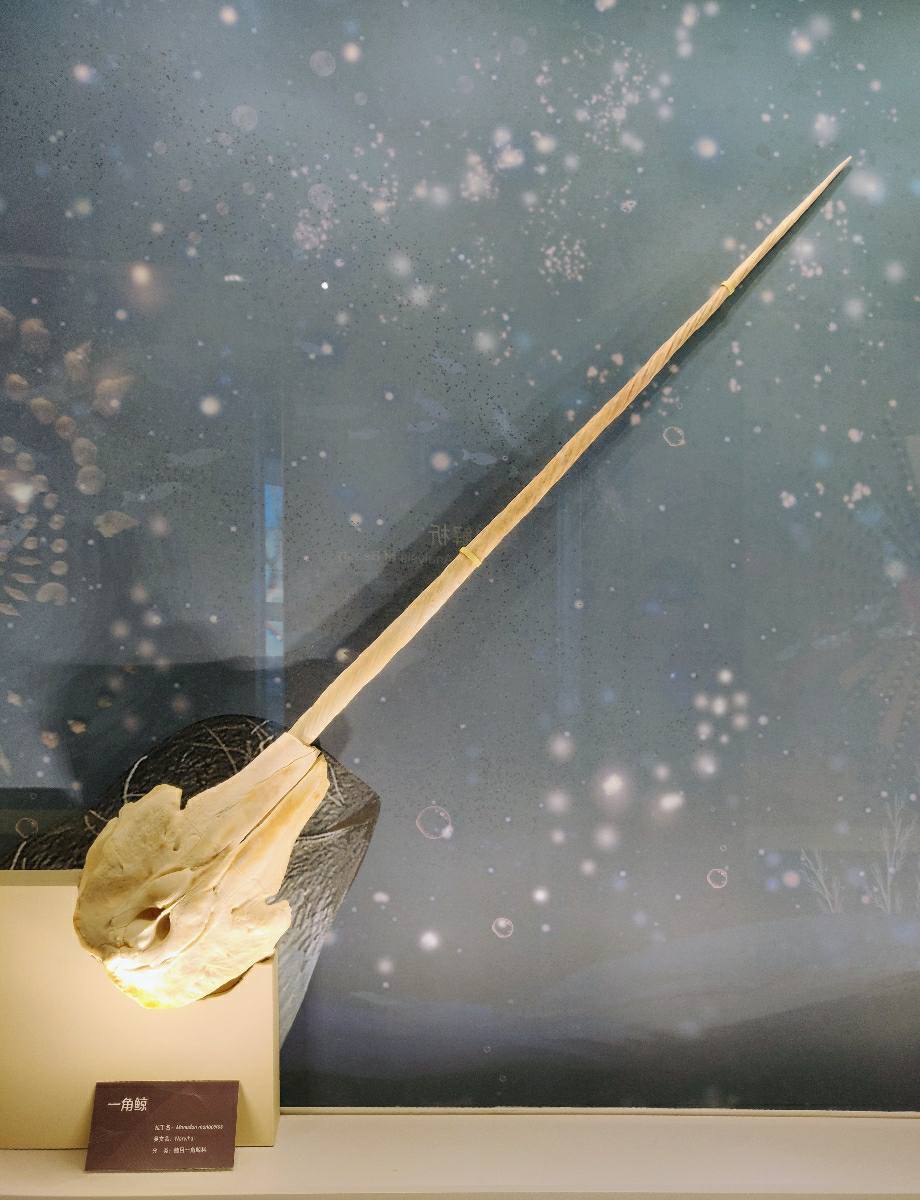

Narwhal

This Arctic whale’s horn remains a mystery. While once thought to break ice for breathing, newer research suggests a more significant role in mating and reproduction.

Shells and color wheel

This exhibit highlights nature’s difficulty in synthesizing blue pigments. As the color wheel approaches blue-violet, the shells become mostly grayish-white. While blue butterflies, flowers, and feathers are common, these organisms don’t actually create blue substances. They employ microscopic structures, a clever optical illusion using other colors.

Golden pheasant neck feathers spread out

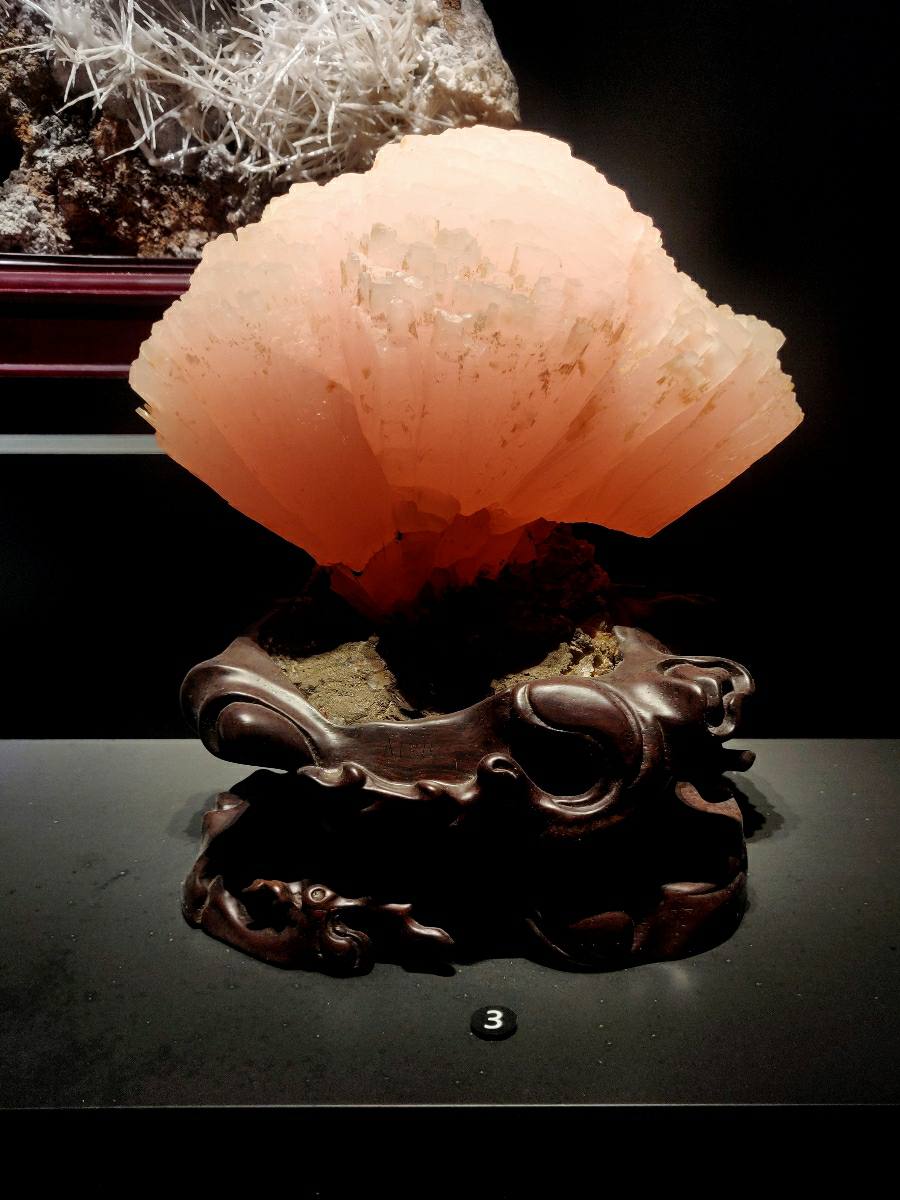

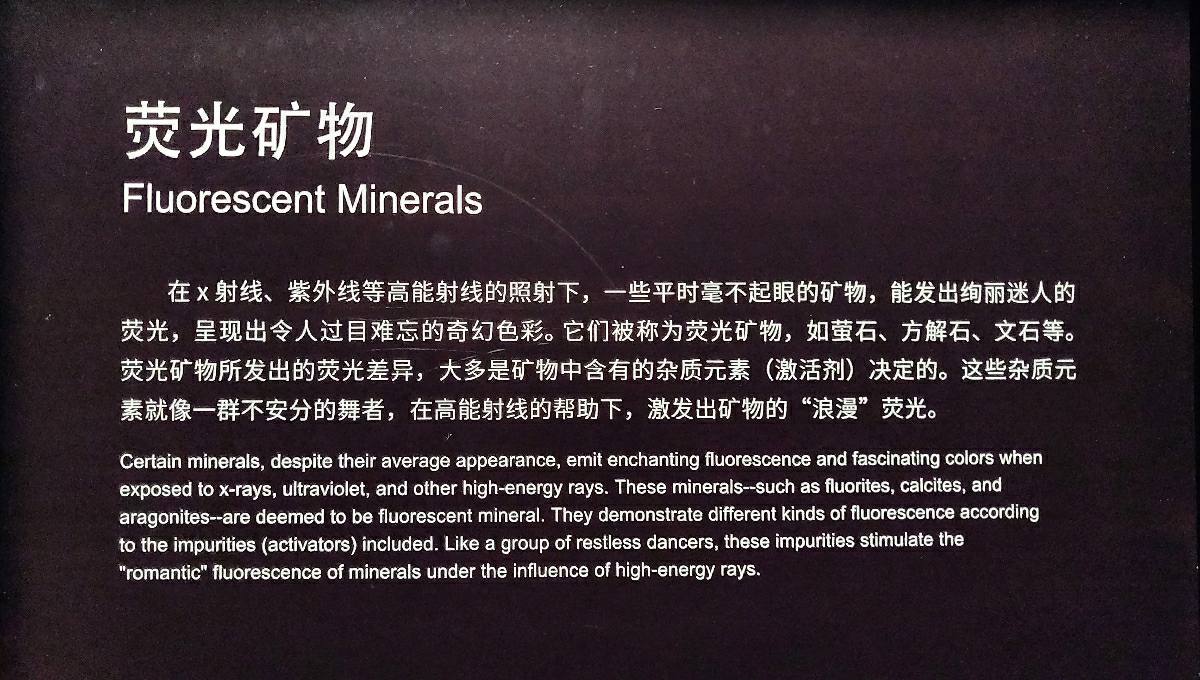

2nd Floor: The Beauty of Non-Life

The 2nd floor showcases the beauty of non-living things – specifically, rocks and minerals. I’m no expert, so I’ll let the pictures speak for themselves.

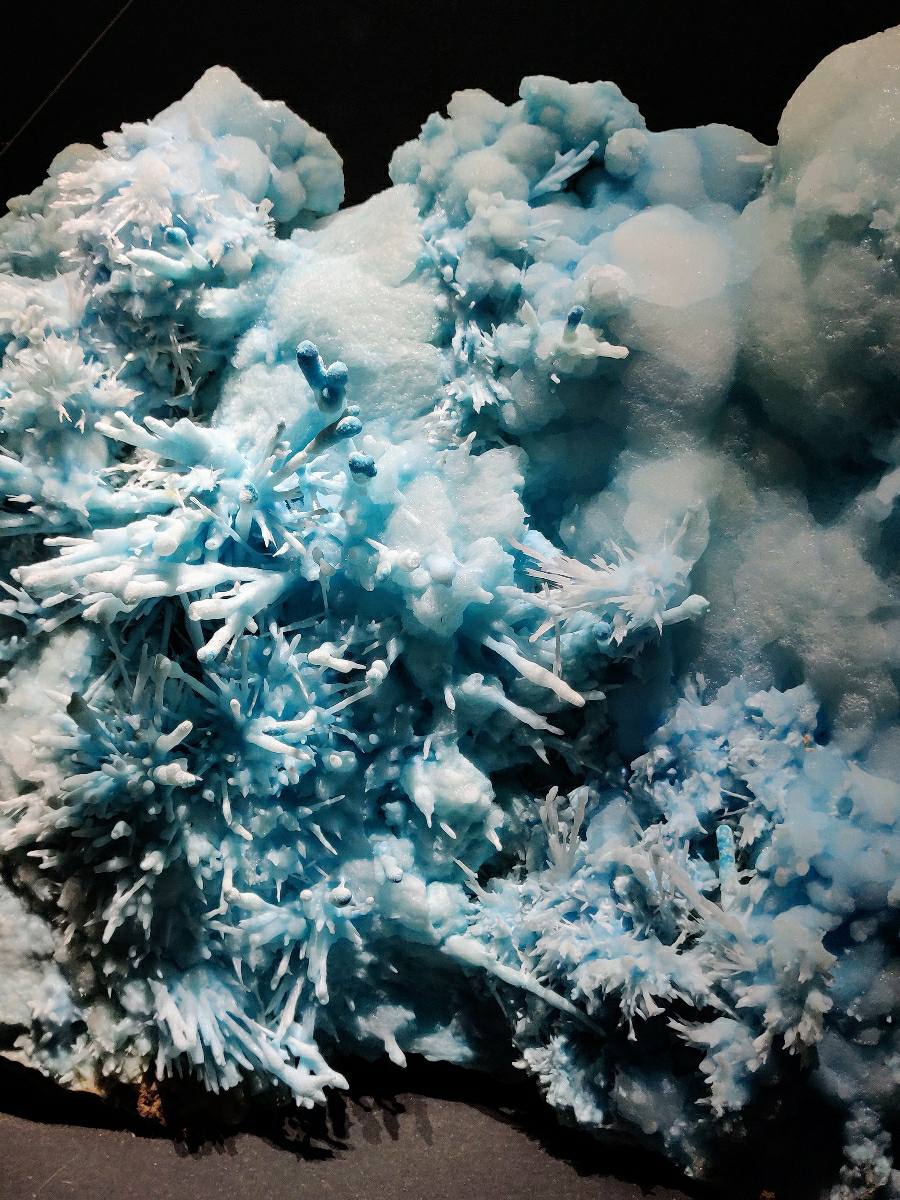

Malachite, the blue color comes from copper

Vivianite

Tanzanite

Tanzanite was my personal favorite, likely enhanced by the lighting. The visual effects of transparent substances under light are quantum phenomena at the crystal and atomic levels. The beauty of minerals is, in essence, the beauty of physics.

Aquamarine

Dinosaur Hall

Short on time, I still decided to explore this hall thoroughly. It was packed with kids, clearly the museum’s main attraction for them.

Stepping inside was breathtaking. A projector mapped images onto a dinosaur model, perfectly synchronized. The projections cycled through the skeleton, internal organs, muscles, and skin – an internal perspective rarely seen.

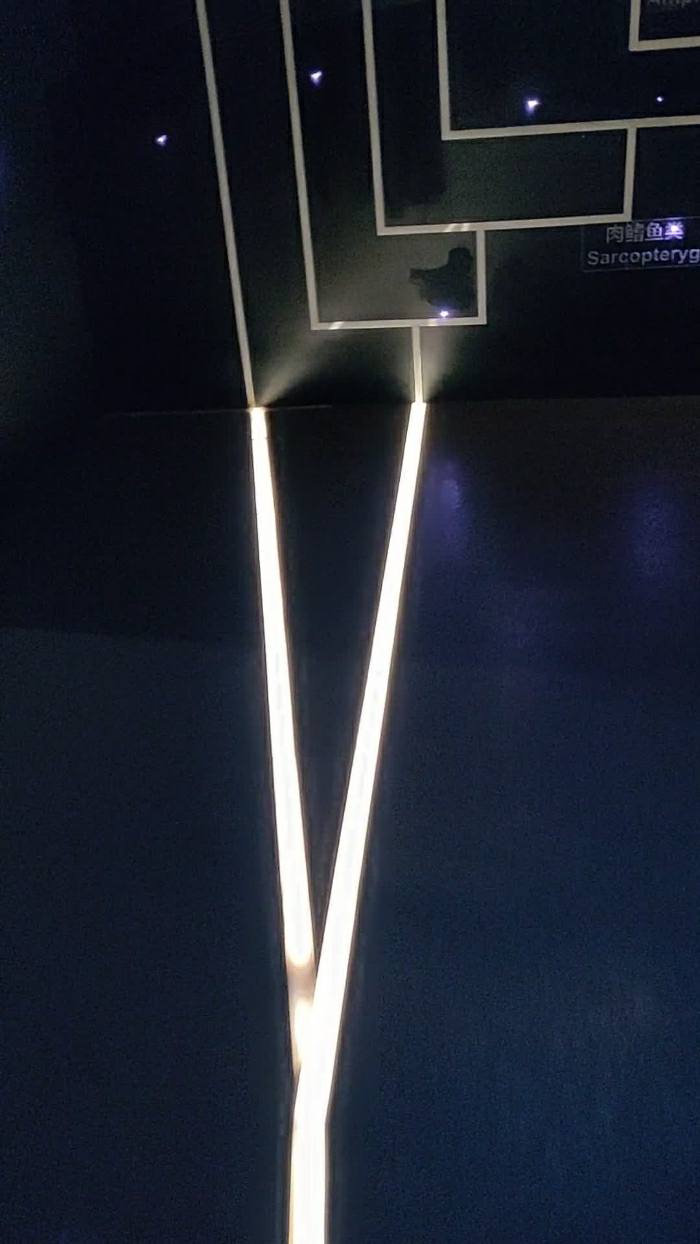

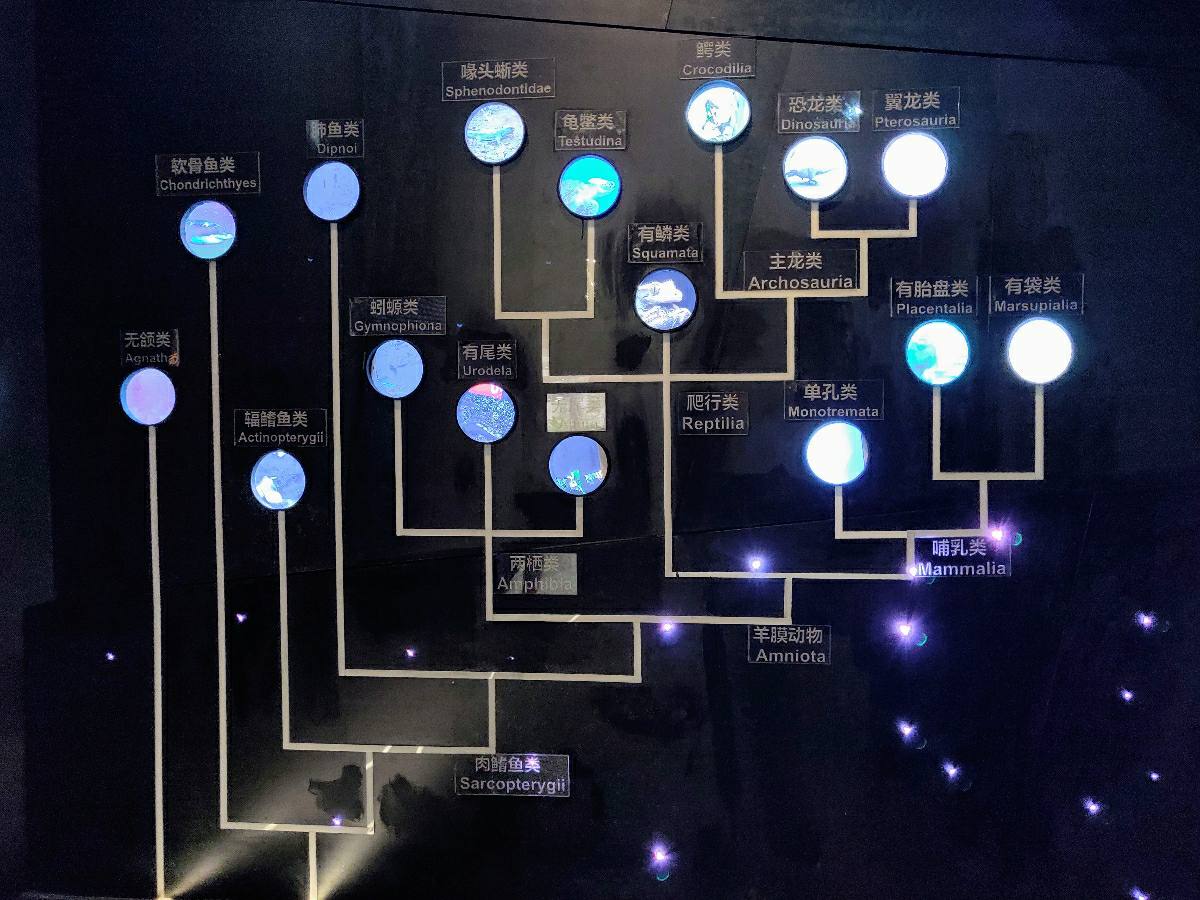

Here’s a hidden gem: easily missed if you’re focused on the dinosaur, it’s a light strip on the entrance floor, pointing to a wall displaying chordate classification.

It’s a metaphor: as chordates, we trace the evolutionary path, witnessing its branching, ultimately finding our place – placental mammals. See the short video: 【浙江省自然博物馆安吉馆-恐龙馆入口处-哔哩哔哩】

Chordate evolutionary tree

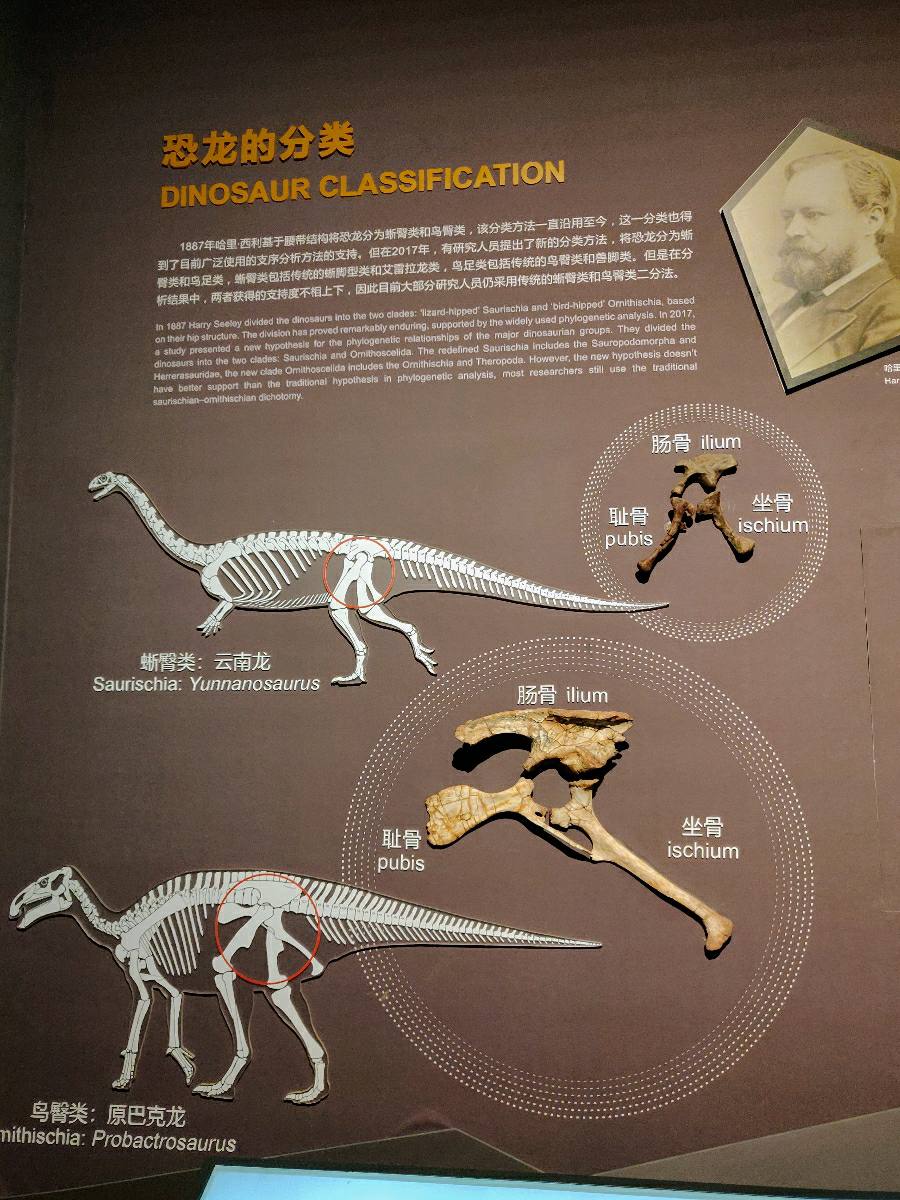

Dinosaur Classification

The second exhibit expands on the chordate evolutionary tree, introducing the dinosaur family.

Dinosaur evolutionary tree

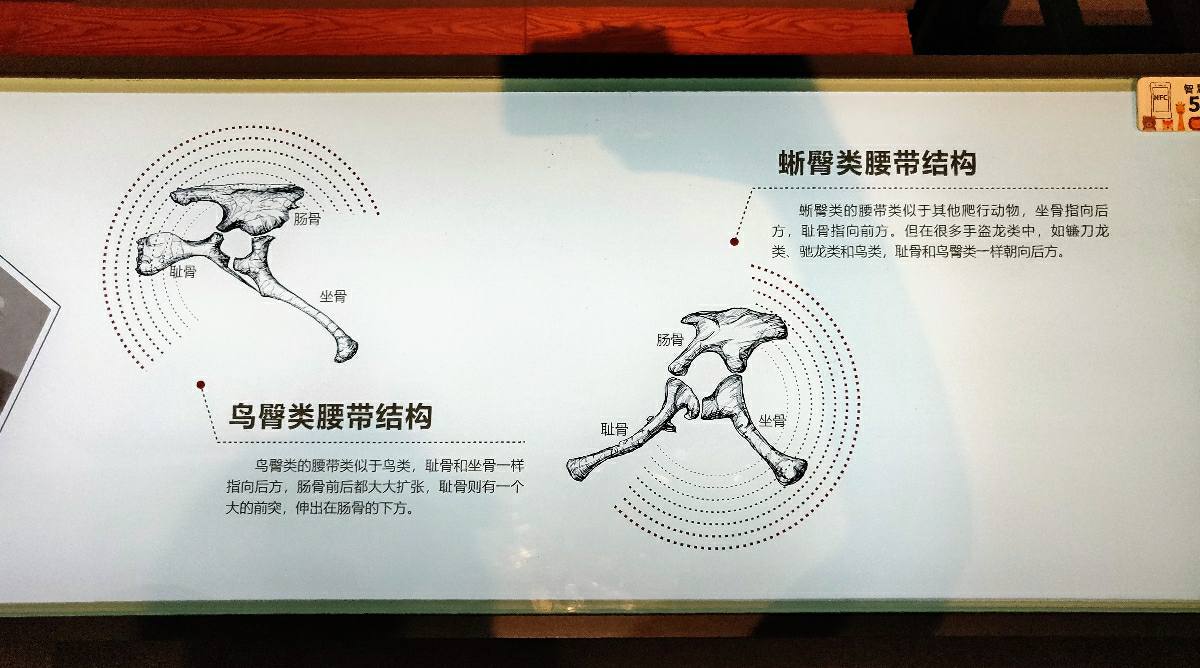

Dinosaurs are taxonomically divided into two groups based on hip structure: Ornithischia (bird-hipped) and Saurischia (lizard-hipped). Ornithischians have a pelvis resembling modern birds, while saurischians resemble other modern reptiles.

However, birds didn’t evolve from ornithischians. Birds’ true ancestors are theropods, a saurischian subgroup. The pelvic similarity between ornithischians and birds is likely convergent evolution.

I witnessed a funny scene here. A mother, explaining the dinosaur family tree to her child, misread it, saying: “Dinosaurs are divided into bird-armed and lizard-armed, got it?” She then quizzed her child: “What kind of dinosaur is Triceratops? Bird-armed. What about Tyrannosaurus Rex? Lizard-armed.”

A classic “tiger mom” moment: expecting mastery from her child without understanding it herself.

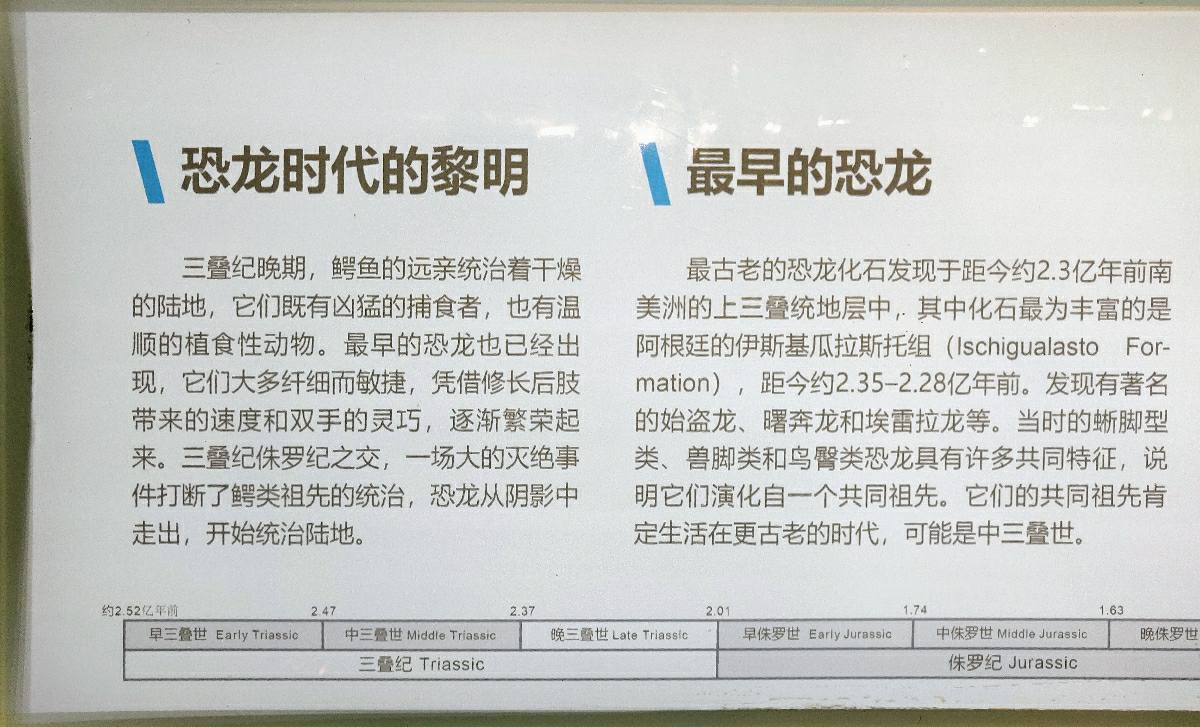

Triassic Period

The Dinosaur Hall is chronologically arranged: Triassic, Jurassic, Cretaceous. Each period features representative species and environments, with numerous fossils and reconstructions.

Dinosaurs originated in the late Triassic.

Across the corridor, the Triassic oceans are depicted. Dinosaurs were land-bound – ichthyosaurs and pterosaurs don’t qualify – but their contemporaneous existence justifies their inclusion.

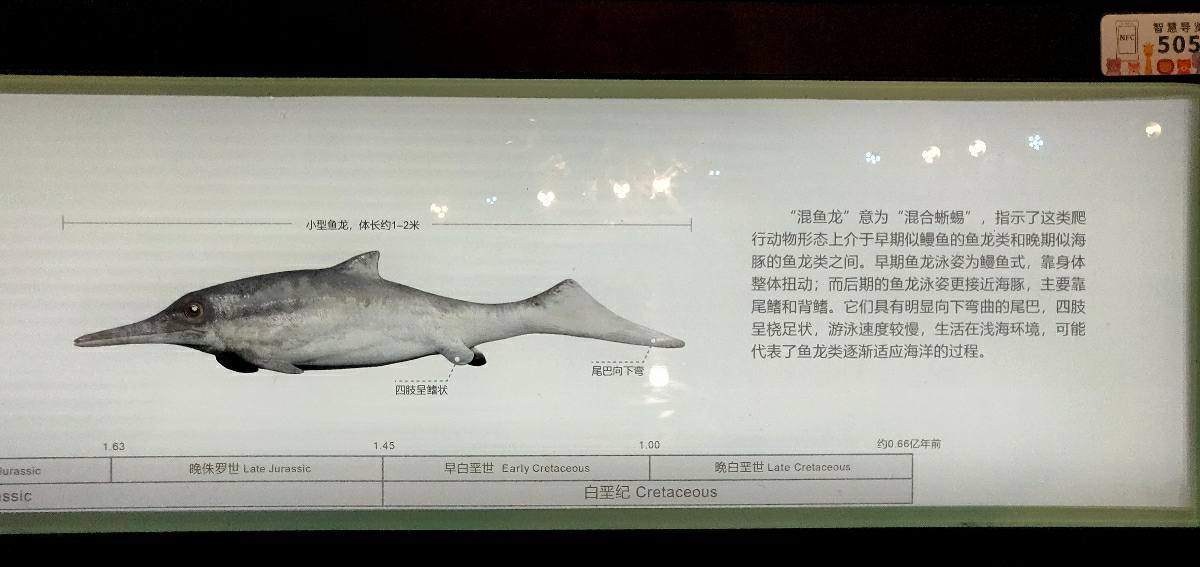

Ichthyosaurs, marine reptiles returned from land, initially swam like lizards, wriggling their bodies. Later forms swam like fish, using only tail fins – a significant adaptation for deep-sea life.

Mixosaurus, with limbs too reduced for walking on land.

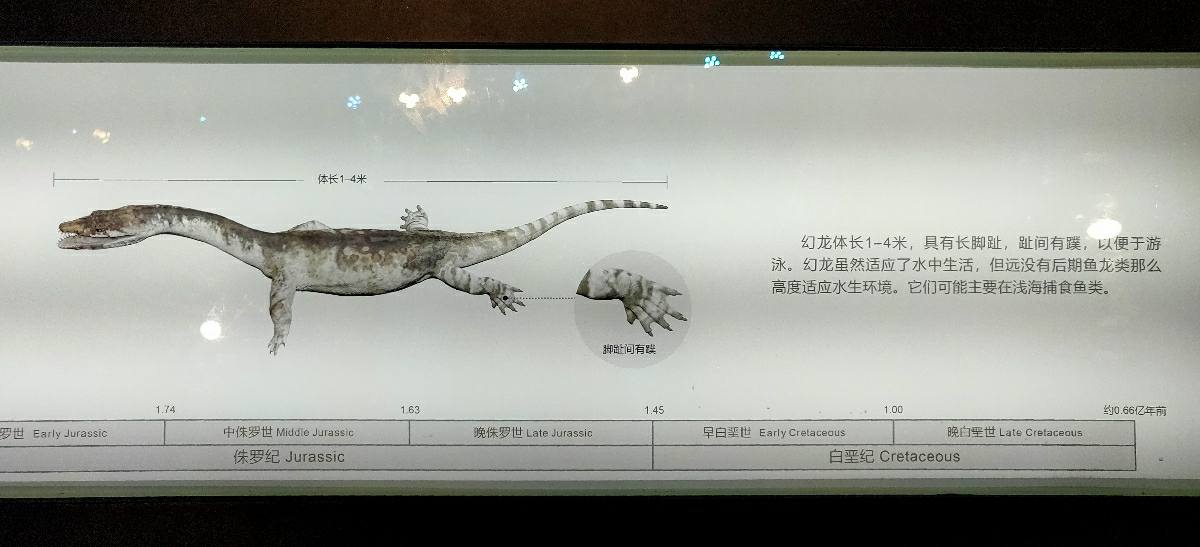

Nothosaurs (pachypleurosaurs) also returned to the sea, but differently. They remained in shallow waters, using webbed toes to paddle and hunt small fish.

Nothosaurus

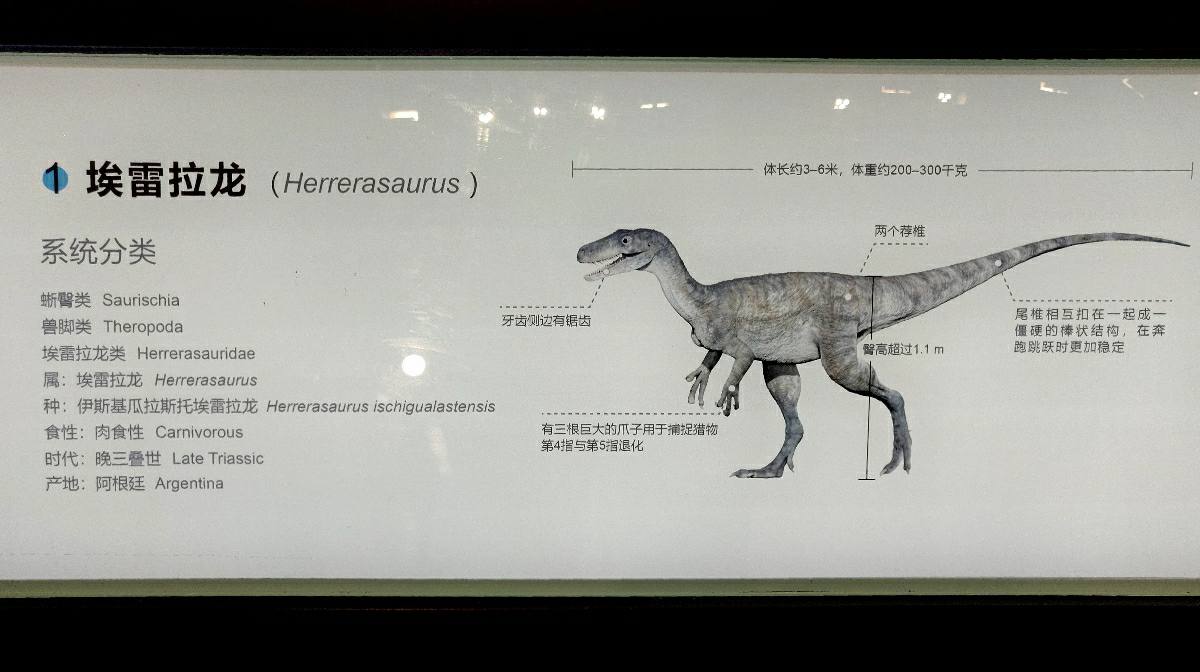

Meanwhile, on land, dinosaurs thrived. Herrerasaurus, though only 3-6 meters long, was a top predator. Its forelimbs were evolving for hunting, with five fingers reduced to three.

Jurassic Period

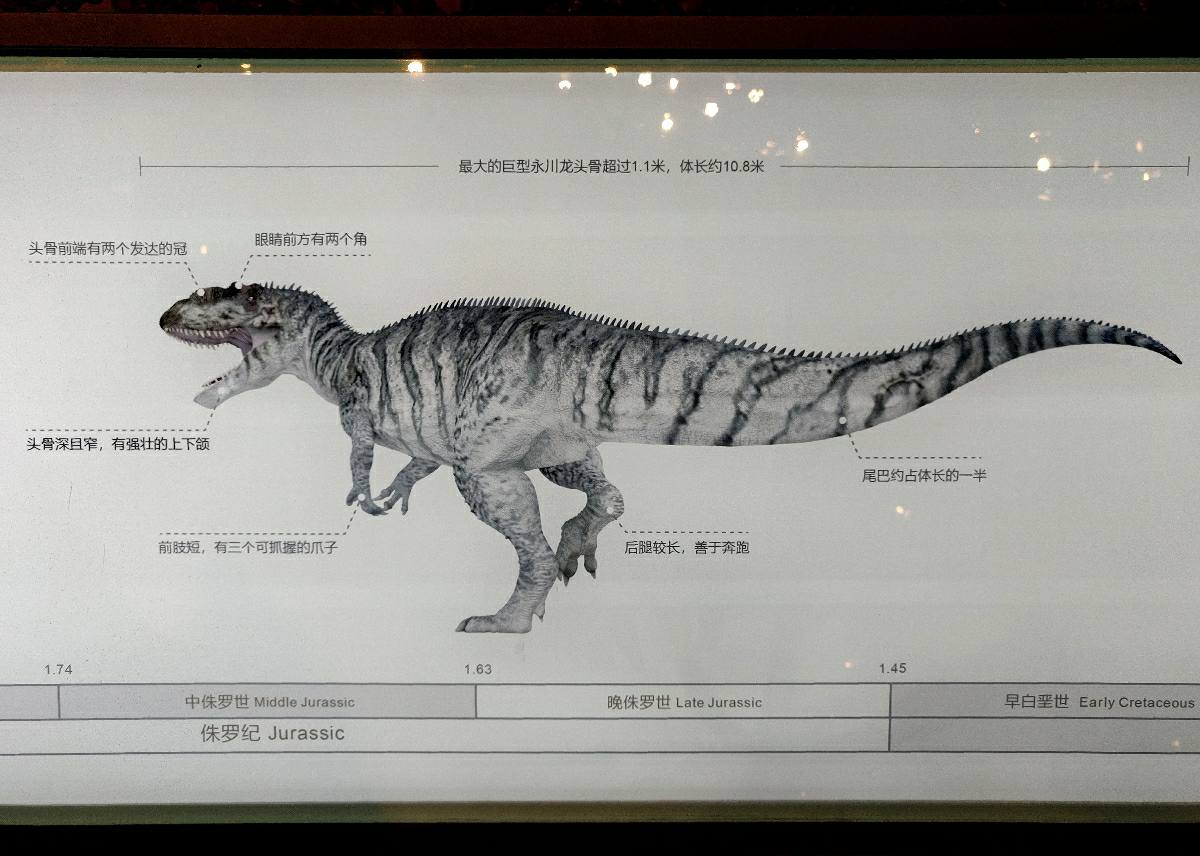

By the Jurassic, land predators had become even more formidable. As you can see, Yangchuanosaurus was much more robust, reaching up to 10 meters in length.

Yangchuanosaurus

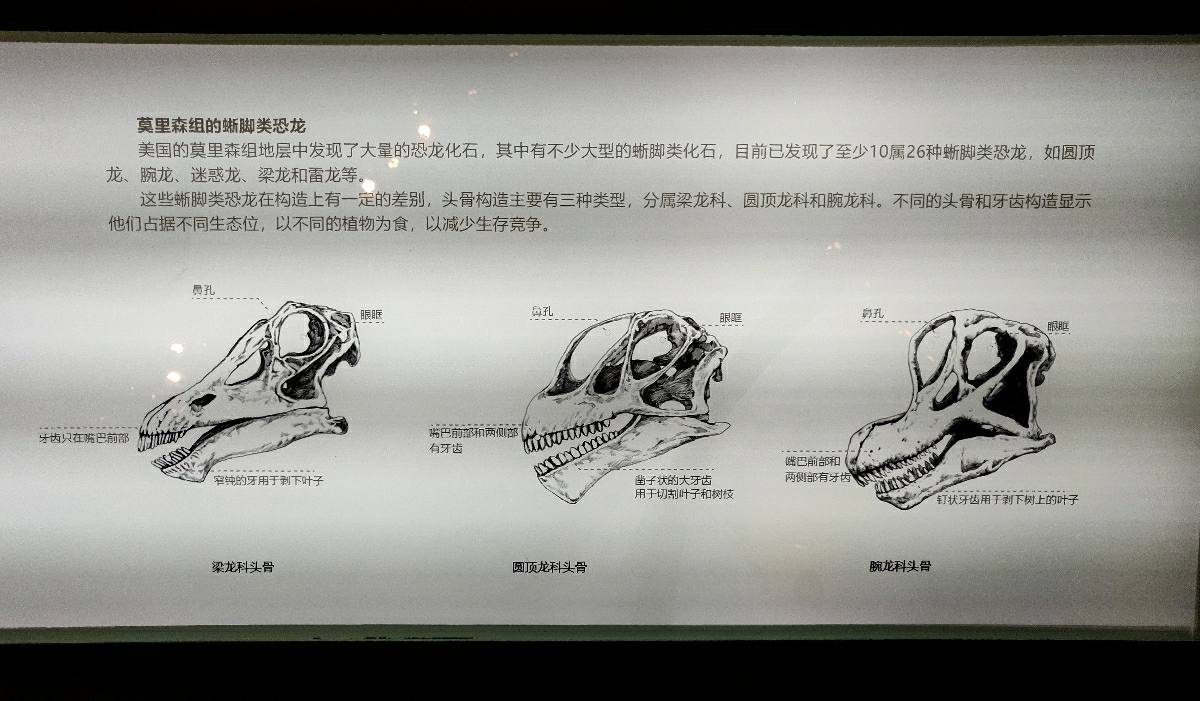

On the herbivore side, sauropods (part of the saurischian group) were diversifying. These were the giants with long necks and tails, like Diplodocus, Brachiosaurus, and Mamenchisaurus.

Take a look at the skulls, especially the teeth. Different tooth structures reflect different feeding strategies – much like the division of labor on the African savanna. Nature always finds a way.

3 types of skulls and tooth functions

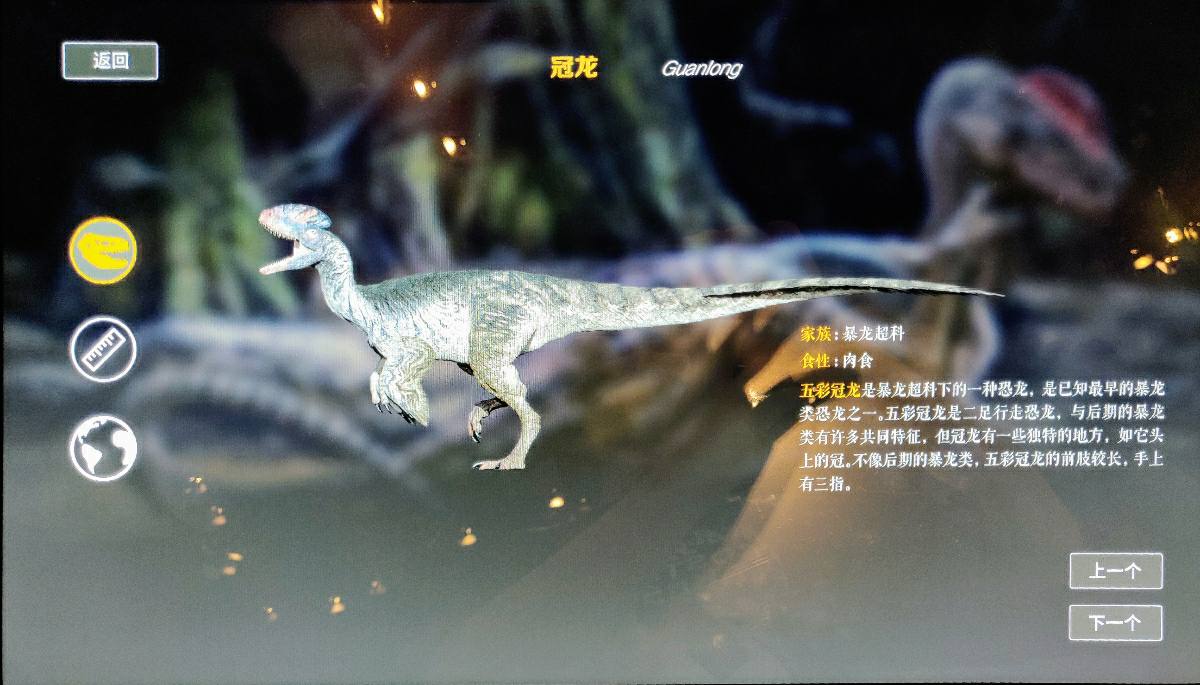

The Jurassic section features a fascinating “Death Trap” scene. Note Guanlong’s appearance – it sports feathers on its forelimbs. Guanlong, a tyrannosauroid, is related to T. rex. As a kid, I always saw dinosaurs depicted as scaly. Later research revealed that some carnivorous dinosaurs likely had feathers. While still debated, it’s now the prevailing view.

Guanlong profile

Cretaceous Period

By the Cretaceous, feathers were even more widespread. Velociraptor, a small dinosaur, was closely related to modern birds. Check out the feathers on its forelimbs and tail; it probably had downy feathers all over.

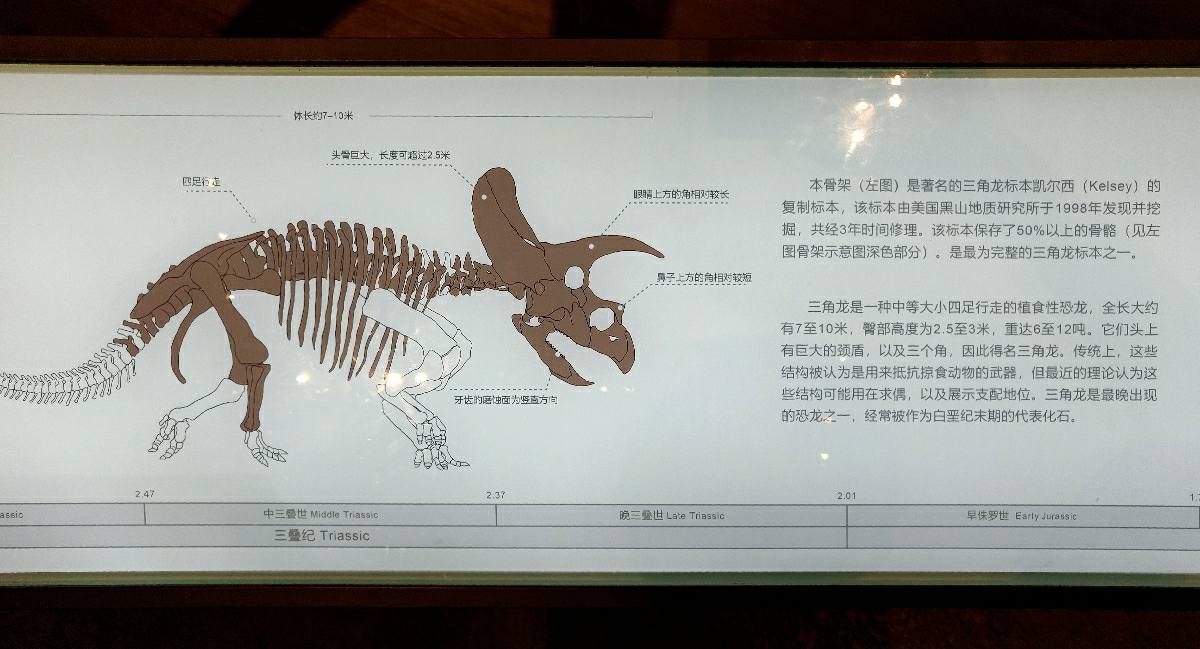

A classic Cretaceous herbivore is Triceratops, one of the last dinosaurs. The caption notes something interesting: while most assume the frill and horns were for defense, recent theories suggest they were primarily for courtship.

Courtship again! First the narwhal, now this. A recent study even suggests giraffes’ long necks evolved for mating, not reaching leaves. Love seems to trump survival – the wild romance of animals. →_→

This Triceratops fossil is remarkably complete, preserving most of the key bones. The display, of course, is a model.

Across from Triceratops stands its frequent adversary, Tyrannosaurus rex. Standing beneath it, gazing up at that massive jaw… the sense of intimidation is palpable.

Don’t scoff at its tiny arms – judging by the skeleton, it could easily win an arm-wrestling match.

While on the first floor of the Dinosaur Hall, look out the windows. The museum has some hidden Easter eggs. One window overlooks a dinosaur sculpture on the lawn – a nice touch.

Dinosaur Lifestyle and Other Reptiles

The second floor of the Dinosaur Hall is smaller. You’re greeted by an animatronic T. rex, surrounded by kids and parents snapping photos.

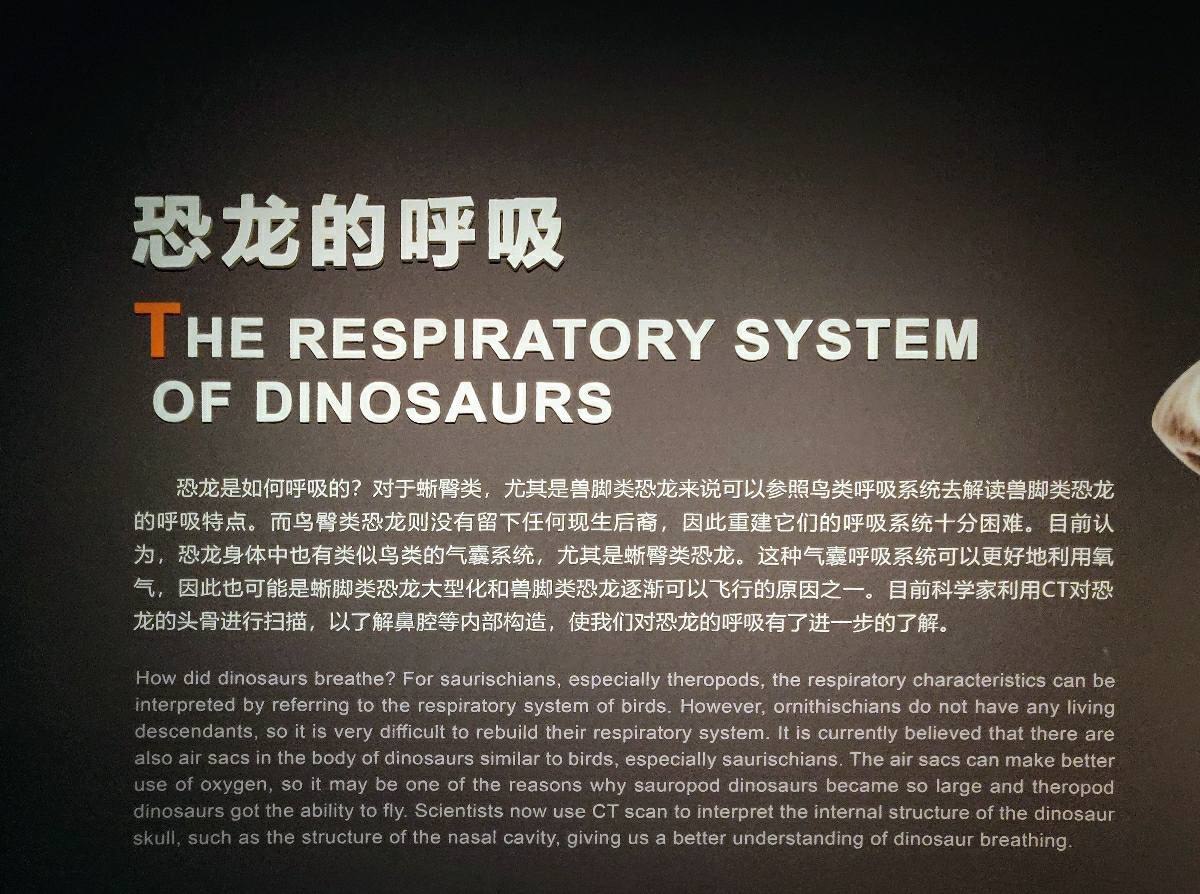

This floor explores dinosaur behavior. It highlights how challenging it is to study ancient animal behavior from fossils. Consider breathing: we can infer about bird ancestors by studying living birds, but the respiration of ornithischian dinosaurs, which have no living descendants, remains a mystery. Respiratory systems leave few skeletal traces, and soft tissues rarely fossilize.

CT scans of skull interiors might offer clues about breathing.

Another major theme on the second floor is the marine and aerial reptiles of the era.

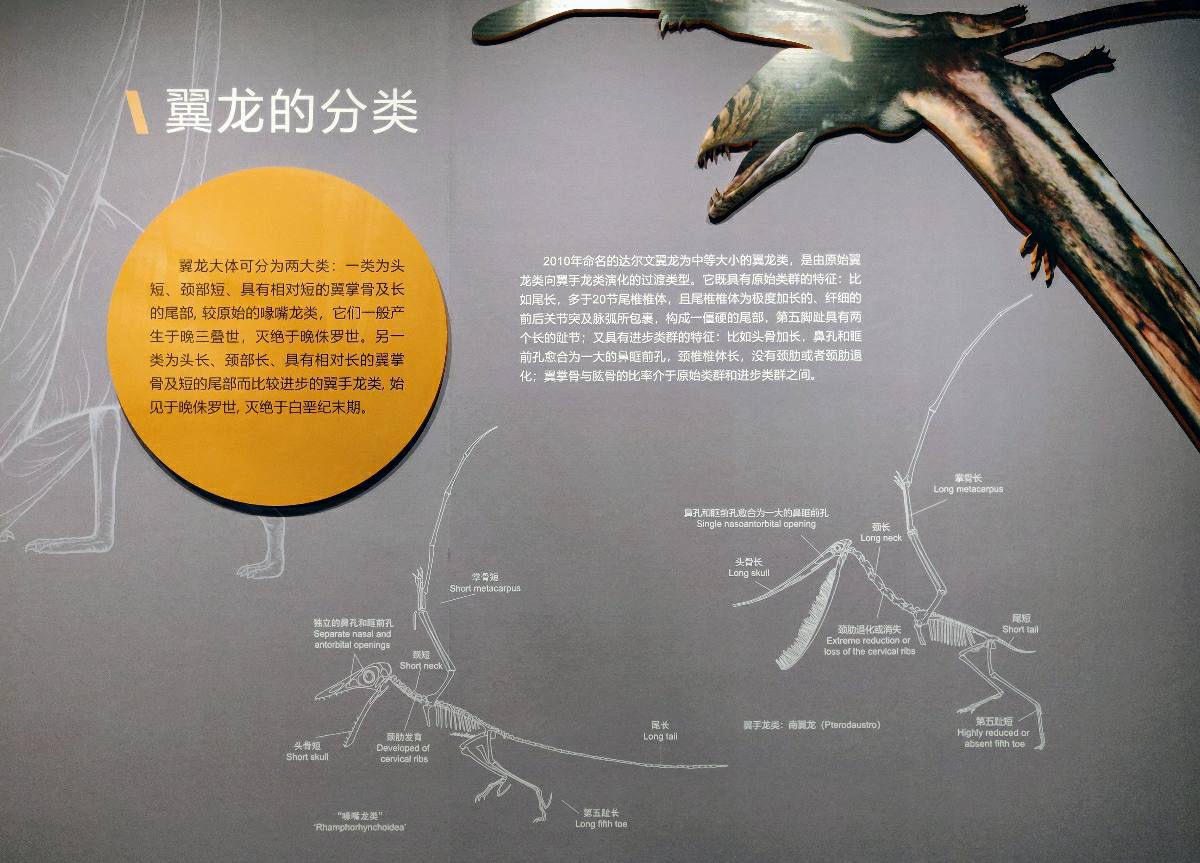

Two different types of pterosaurs and their periods

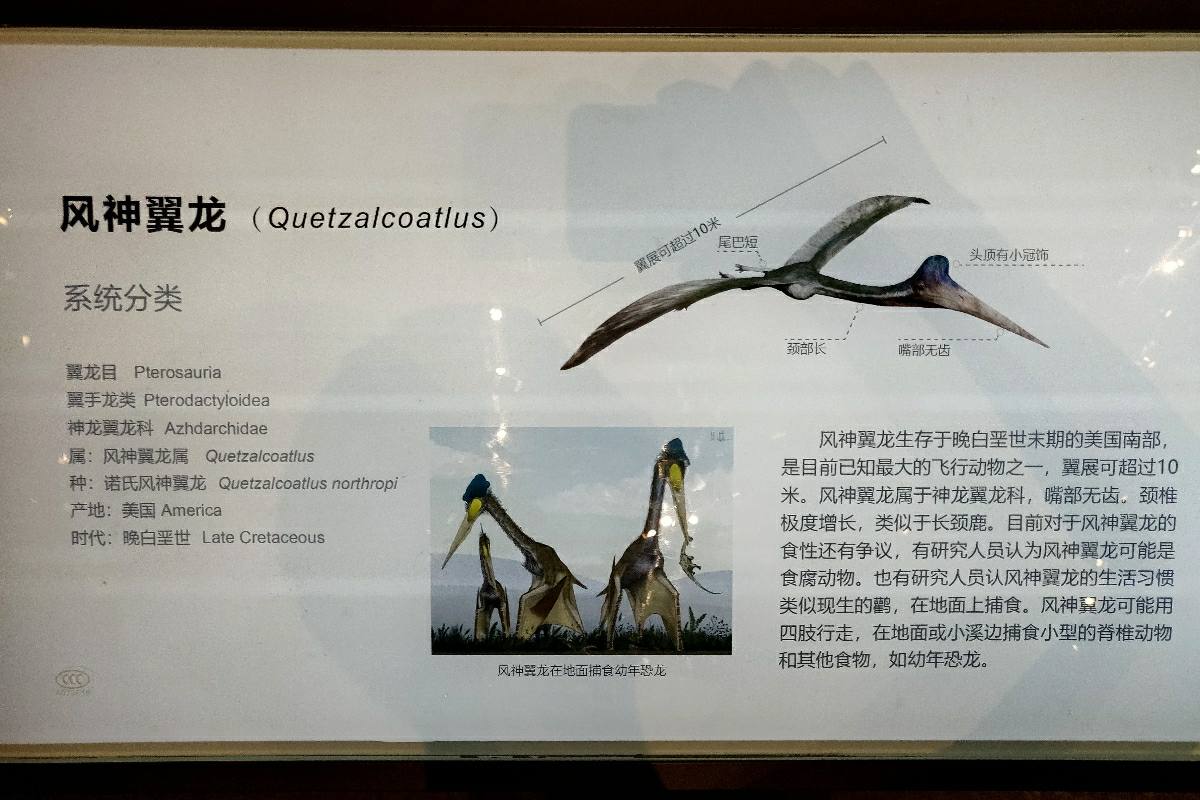

A 10-meter wingspan – imagine that.

Marine reptiles also have their evolutionary tree.

Ecology Hall

This hall is massive, but I only had 40 minutes left. I had to speed through, but I grasped the main points.

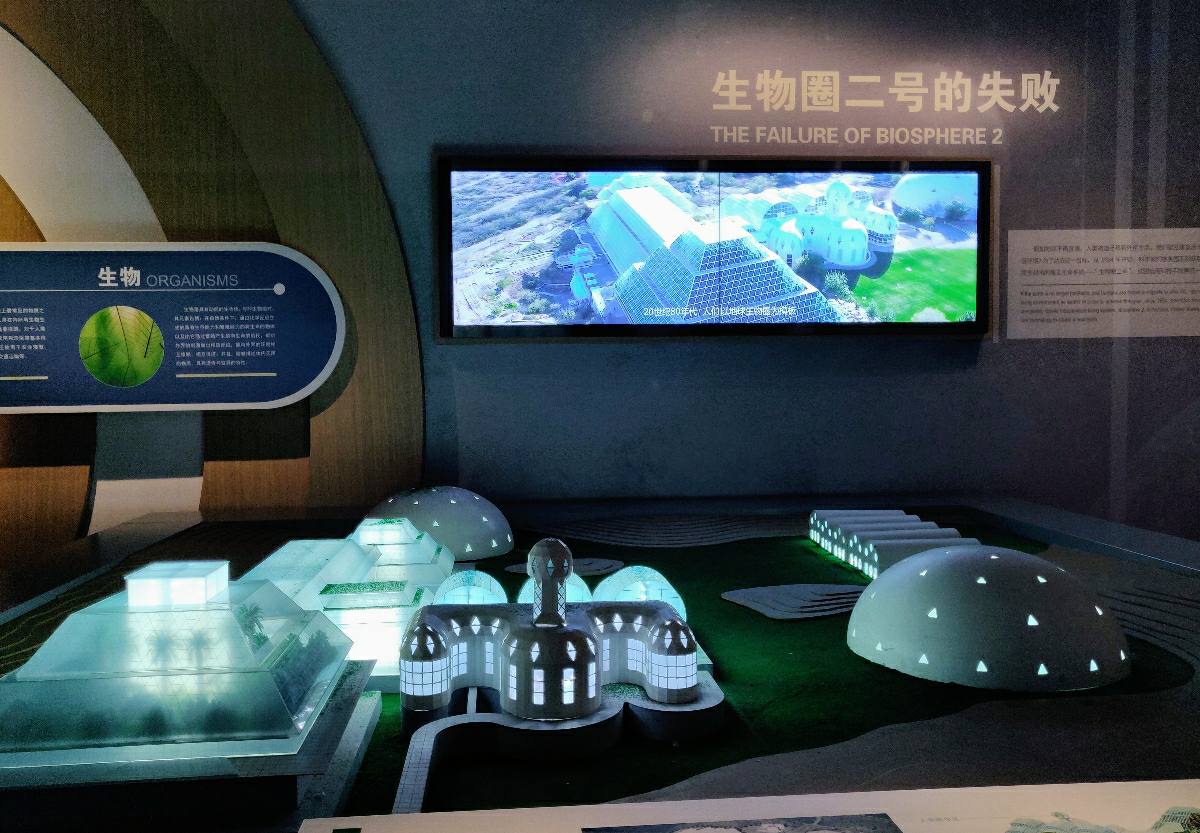

It begins with the Biosphere 2 experiment, a failed attempt at a self-contained ecosystem. Why did it fail? Keep that in mind. The hall underscores ecosystem complexity from multiple perspectives.

The hall dedicates considerable space to explaining ecosystem components: producers, consumers, decomposers, their functions, food chains, and how water, carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycle through nature. It adopts a wider view, focusing on interspecies relationships and interactions, rather than on individual organisms.

This small display exemplifies this. While the previous five halls would’ve highlighted a single moment in a pine moth’s life, here, its entire life cycle is shown. I’ve often seen the larvae and adults, but never connected the two.

Given the ecological theme, the hall meticulously recreates species’ habitats. The initial exhibits realistically depict several natural environments.

Beetles in their element.

There was a truly impressive section I couldn’t photograph due to time constraints. It consisted of dioramas, akin to those in the Geological Hall, each portraying a different environment and its characteristic species: subtropical desert, North American prairie, alpine tundra, and so on. The animal specimens and settings were incredibly immersive, resembling exquisite crystal balls.

Next, a unique circular area presents interspecies relationships and interactions, each accompanied by a short nature narrative and a realistic scene. This space truly highlights the museum’s creative approach.

Check out the short video: 【浙江省自然博物馆安吉馆-生态馆物种相互作用-哔哩哔哩】

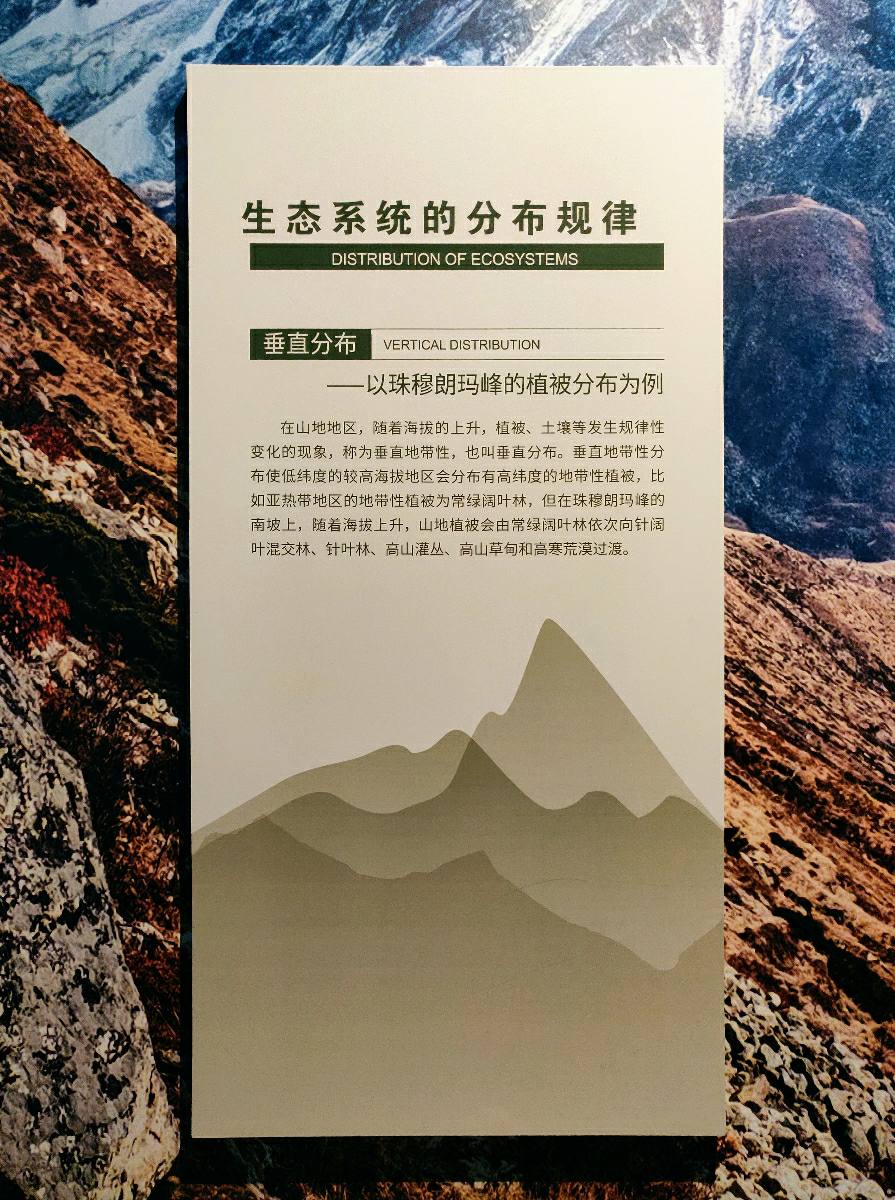

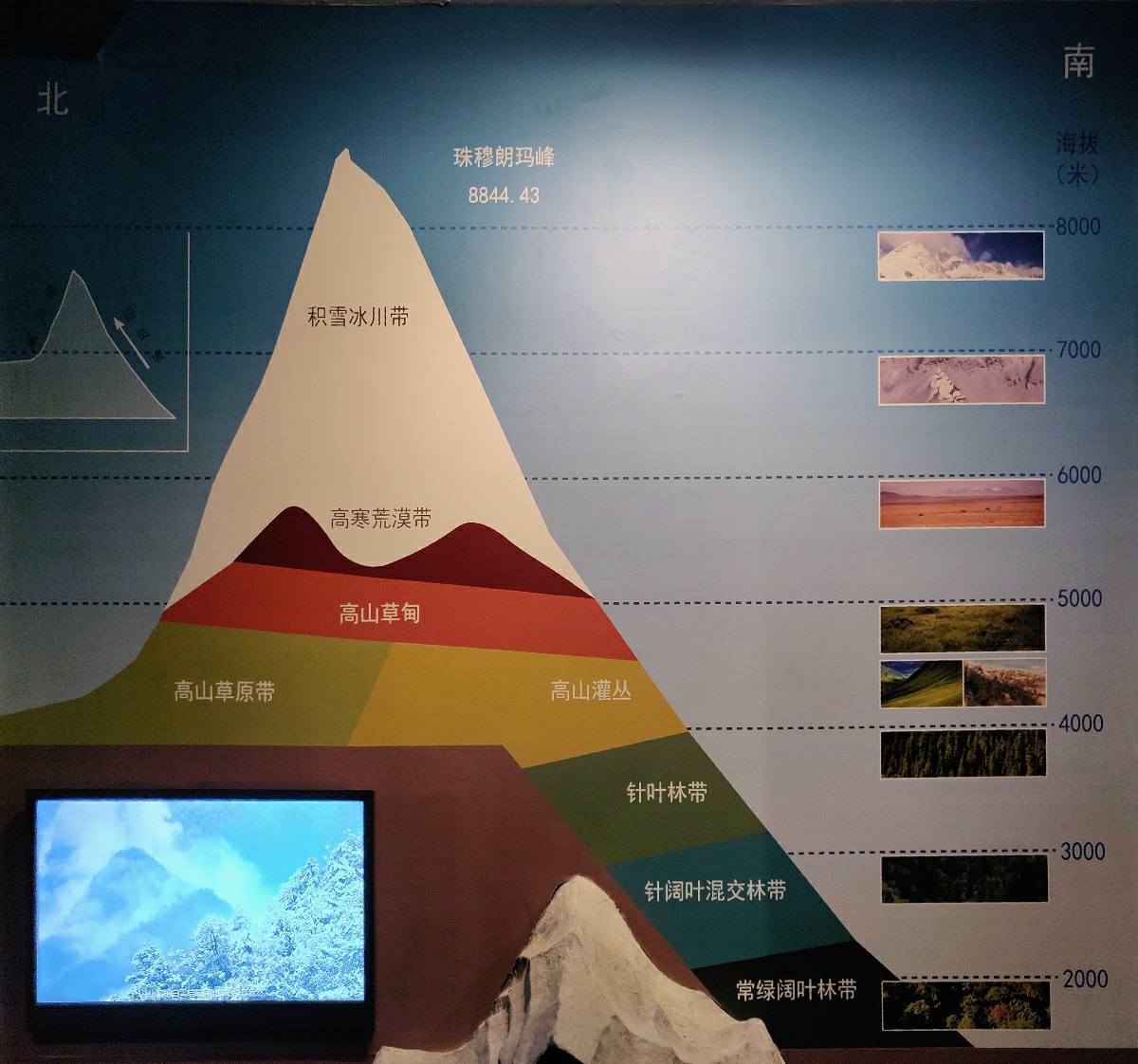

Here’s another interesting point, one most people (myself included) likely haven’t considered: Ecosystems vary not just by location, but also by altitude within the same location.

Mount Everest serves as a prime example. Its 8,000-meter elevation encompasses seven ecosystems, with distinct differences between the windward and leeward sides.

The hall also explores how various natural factors influence ecosystems. While discussing rainfall, I came across an engaging interactive exhibit.

The diagram indicates that visitors can drag the screen below to alter the rainfall in the animation, which in turn changes the vegetation. The museum’s intention was to allow visitors to modify precipitation and observe the ecosystem’s response. Sadly, the device malfunctioned; regardless of the dragging, the animation consistently displayed a rainforest.

Further along, there’s more on ecosystem roles and conservation, but I’ll skip the details.

Near the exit, the initial question is finally answered: Why did Biosphere 2 fail?

Naturally, the answer extends beyond those few lines. A small theater screens a film about Biosphere 2. I was eager to sit, watch, and enjoy the yogurt I’d packed. However, with closing time nearing, I only managed a brief look.

The film noted that Biosphere 2 contained an overabundance of decomposers, disrupting the balance with other system components.

Conclusion

My overriding feeling during the latter half was a lack of time; I had to rush. Even so, the museum was thrilling overall. I highly recommend it.

Two minor issues:

- While the video content is high-quality, some footage is quite blurry, likely from older sources.

- Insufficient lighting. I frequently encountered text panels in dimly lit corners, making them difficult to read.

Finally, some advice for those planning a visit to the Zhejiang Museum of Natural History, Anji:

- Book the afternoon session; it’s an hour longer than the morning one.

- Even with the four-hour afternoon session, prioritization is key:

- If you have kids interested in animals, concentrate on the Behring Hall, Ocean Hall, and Dinosaur Hall.

- For those keen on the broader evolutionary narrative, focus on the Geological Hall, Behring Hall, and Ecology Hall.

- If you simply want to appreciate nature’s beauty, prioritize the Behring Hall, Natural Art Hall, and Ecology Hall.

- The museum is less than a 30-minute drive from Anji town, so you can grab a bite there beforehand.

- The museum offers convenient underground parking.