I previously explored camera lens principles and “optical zoom” on phones: https://victor42.eth.limo/post/3645/

I noted that flagship phones typically have three cameras: a moderate focal length (20-35mm) for everyday shots, a shorter one (under 20mm) for ultra-wide-angle and macro shots, and a telephoto lens (over 50mm) for distant subjects.

So, will phones ever evolve to include 200mm or even longer lenses? Imagine photographing birds with just your phone! I’ve researched this further and have some new insights.

Longer Focal Length Means Longer Lens

First, I confirmed my hunch: longer focal length means a longer lens. The core optical component is the lens assembly, made of multiple convex and concave elements.

A fisheye lens, for instance, uses many elements to gather light from a 180° field of view, bending it gradually into nearly parallel beams. These are then adjusted to project a clear image onto the sensor.

Many factors influence lens length, and the internal optics are complex—far beyond my grasp. But focal length is key. To simplify, let’s recall basic optics: treat the assembly as a single lens.

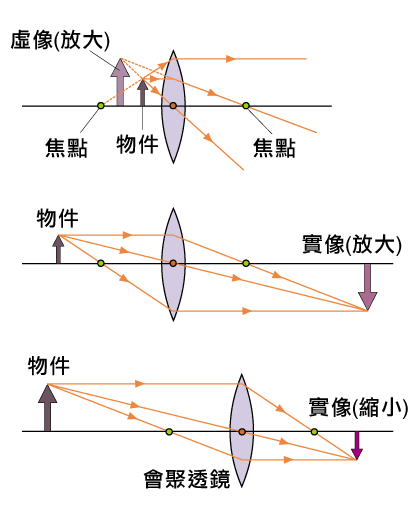

Focal length is the distance from the lens’s center to the focal point. A lens with a given curvature always has a fixed focal point. The subject is usually much farther than twice the focal length (the third case above), creating a smaller, real image on the sensor.

The imaging formula is 1/f = 1/u + 1/v (f = focal length, u = object distance, v = image distance). With fixed f, the farther the object (larger u), the closer the image forms to the focal point (v approaches f). Since u is much greater than v, the sensor sits slightly beyond the focal point for a sharp image. Use a longer focal length, and the sensor must be farther away.

Thus, even a simple telephoto lens, with one element, needs that empty space to achieve its focal length. A complex, real-world lens also requires sufficient internal space.

This highlights the bottleneck: it’s physics. No matter how advanced technology gets, a 200mm lens can’t be as short as a 50mm one.

The Mountain of Physical Limits

Smartphones started sporting multiple rear cameras a few years back: a high-res main camera plus lower-res auxiliaries. These auxiliaries generally had focal lengths under 50mm. It’s not that manufacturers haven’t considered a “birding phone”—it’s physics.

Consumers do want telephoto lenses. Those who want them enough accept a price premium and a camera bump.

This is physics pushing back. Engineering yields. If a 50mm lens needs a bump, a 200mm one would likely be thicker than the phone. Phone birding seems impossible.

Smartphone history shows two trends in component performance:

- Exponential growth: megapixels, storage.

- Approximate logarithmic growth: focal length, screen size.

The first hasn’t hit limits; the second approaches them asymptotically. Portability limits focal length and screen size. They could grow, but the phone would become something else, exiting the mainstream.

Extending this, most physical limits (besides, say, light speed) are actually human body limits. Our bodies haven’t changed much in millennia, and civilization is built around them. Stair height, table height, traffic light colors, shower gel fragrance—all relate to the human body. Different humans would mean a different civilization.

Over the Hill

So, is phone birding truly impossible?

Let’s reframe: not “how to make a 200mm lens as short as a 50mm one,” but “how to fit a 200mm lens in?”

Shortening it is impossible, but fitting it in? That’s where ingenuity comes in. Limits can’t be broken, but they can be bypassed.

I recall seeing “periscope lens” on my phone’s spec sheet. I get it now. It bends light 90 degrees, like a periscope. The lens is too long for the phone’s thickness, so clever engineers used the phone’s width!

One of my phone’s cameras is square—a periscope lens hallmark. The square aperture and reflector boost light intake, compensating for the tucked-away lens.

Surging Forward

This reframes innovation for me. I knew the principle, but this made it click.

Clever innovations that solve big problems deserve praise. But these specific ideas aren’t as valuable as we think. Could only one person think of laying the lens down? The real challenge is committing resources to overcome the resulting hurdles.

Given time, these workarounds—bypassing limits with engineering—are inevitable. If one person misses it, another will likely propose something similar. Consumer demand, even latent, drives producers.

Semiconductor memory is cutting-edge, right? When processes approached quantum limits, some thought performance and capacity gains were over. But 3D stacking used vertical space, bypassing the limit and boosting capacity. The industry dances on the edge of limits, constantly breaking through.

What seems truly valuable is humanity’s collective innovative capacity—the flexible ability to explore, push boundaries, and maximize existing technology. A social structure that encourages, not suppresses, this is key to progress.