During the Spring Festival, I dove into some tech projects I’d been curious about. The best way to learn is by doing – using the tech, reading the docs, and getting hands-on. This led me to move my blog to the blockchain.

And it worked! My new blog is at https://victor42.eth.limo/. Eventually, when blockchain browsers are common, I might just use https://victor42.eth/, the actual address.

This is a long post, so here’s a summary of what’s covered, and the background you’ll need:

- Traditional Web: A basic overview of how websites are accessed. No prior knowledge needed (hopefully!). Skip this if you’re familiar with networking.

- Ownership on the Traditional Web: What a website owner does to publish, and who controls each part. No prerequisites, but easier if you own a website.

- New Tech Explained: How websites work in the blockchain world, compared to the traditional web. You’ll need a basic understanding of blockchain, Ethereum, and BitTorrent.

- Putting the New Tech into Practice: Tools and steps to deploy your own blockchain website. You’ll need experience building traditional websites, understanding DNS, and setting up a static site on GitHub. For a blockchain domain (optional), you’ll need to understand crypto wallets, transactions, and buying Ether.

The Traditional Web

I’ve been exploring ENS and IPFS, which I’ll explain later. First, let’s see how my blog worked before.

Key components include the domain name, DNS, IP address, and server. Accessing a website is like sending a package.

Imagine sending a gift to a friend at the Palace Museum. You need their address. They receive it and send you postcards in return.

Domain Names

My blog was previously at https://victor42.eth.limo/. I’ll keep that domain for about six months, but I don’t plan to renew it.

A domain name is a website’s nickname, making it easy to remember. Sharing the domain lets others access your site.

A website can have multiple domains. However, a domain can only point to one website. It’s first-come, first-served.

Think of “The Palace Museum” – everyone knows it. But asking for directions in a Guangzhou dim sum restaurant might get you strange looks.

Knowing the name isn’t enough.

DNS, IP, and Servers

DNS (Domain Name System) points a domain name to an IP address.

DNS needs DNS servers to work. Think of these as large machines in a server room – just the unit, no monitor or keyboard. They’re usually controlled remotely.

You likely encounter IP addresses with your router (e.g., 192.168.1.1). This number string is your router’s location on your home network. Typing it into your browser usually opens the router’s settings. On the internet, IP addresses can represent PCs, phones, cell towers, cameras, servers…

When you visit a website, the IP usually points to a server storing the website’s code and data. Your browser uses DNS to find the IP and tells the server to send the content. The content appears in your browser.

Back to the real world, DNS servers are like people guiding you. You ask, “How do I send something to the Palace Museum?” A grocery shopper says, “Ask someone younger.” A Starbucks barista says, “Ask someone in Beijing.” A colleague from Beijing says, “It’s 4 Jingshan Front Street, Dongcheng District, Beijing.”

People who know tell you directly; others point you to someone else. This relay gets you the address, the Palace Museum, from just the name. That’s how DNS servers work. The IP is like the street address, unique without duplication. You send your gift. Your friend sends back postcards, showing the Palace Museum’s beauty (like the server sending website content).

IP addresses are unique in both directions. One address, one place.

Ownership on the Traditional Web

That’s how accessing a website works. But who controls each part?

We’ve looked at it from the visitor’s side. Now, let’s see what a website owner does to make their site visible.

Domain Names

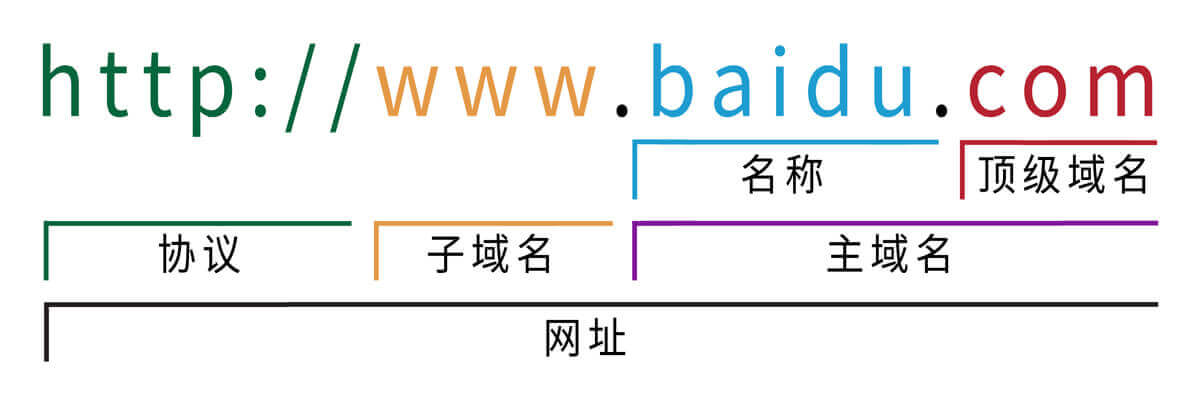

Let’s examine a familiar URL:

It has four parts:

- http://

- www

- baidu

- com

http:// is the protocol (HyperText Transfer Protocol). It’s an agreement between your browser and the server on how to transmit information.

Other protocols exist. But HTTP is standard for websites, so we often omit it and just say www.baidu.com.

Let’s discuss the other three parts in reverse.

com is the top-level domain (TLD), categorizing websites. Examples: .com (company), .edu (education), .mil (military). Two-letter TLDs represent regions (e.g., .cn for China, .uk for Britain).

ICANN controls top-level domains. It decides which names can be TLDs. See the allowed TLDs here: https://data.iana.org/TLD/tlds-alpha-by-domain.txt. ICANN is a non-profit, but with enough money, you might get a TLD.

Apple registered .apple (different from apple.com; it’s xxx.apple!). They could use iphone.apple, ipad.apple… shorter than apple.com/iphone.

But .com is ingrained. People say it automatically. You only need the brand name, apple, and add .com. Registering .apple is mainly brand protection.

.com is so common because of commerce. Businesses register and maintain domains to build brands and drive revenue. They have more incentive than educational institutions or non-profits. So, .com became dominant, broadening its meaning.

baidu is part of the main domain. With the TLD, it forms the complete main domain. Baidu.com means “a company called Baidu.” Baidu bought this domain and pointed it to their search engine.

Domain registrars and cloud providers control main domains, charging annually. GoDaddy is well-known internationally; in China, there’s Wanwang, Ename, Alibaba Cloud, and Tencent Cloud. You choose a domain and pay for a few years. You can use it and point it anywhere. But the service provider still owns it and can take it back.

www is a second-level domain, or subdomain. www.baidu.com and baidu.com are different.

Owning the main domain (baidu.com) lets you add subdomains through your registrar or DNS provider. For example, help.baidu.com (customer support), map.baidu.com (Baidu Maps). www points to the search engine, like the main domain.

Why the redundancy? “www” means World Wide Web. Early on, websites weren’t the internet’s core. Domains were used for email, file transfer, etc. Websites were another service. So, www indicated the official website. Later generations did the same, even without other services. People still do it, forgetting why.

Subdomains belong to the main domain. You control their usage, but the registrar owns them.

As an aside, the domain name order seems reversed. But the internet’s inventors were Western, especially English speakers. English addresses go from smallest to largest:

#20A, 2345 Belmont Avenue, Durham, NC, 27700

Building, street, city, state. It’s a cultural difference.

DNS

Don’t announce your domain yet. Typing it in a browser won’t work. It’s not pointed to a server. Pointing is called domain resolution.

A domain points to one website. Resolution rights are crucial. Whoever controls them decides where the domain is used.

Initially, resolution rights are with the domain provider. But specialized DNS providers offer better services (Cloudflare internationally, DNSPod in China). To use them, transfer resolution rights from the registrar to the DNS provider. Then, set the domain’s destination in the DNS provider’s interface. DNS services often have free and paid features.

The DNS provider now has resolution rights. You control where the domain points, but it’s not 100% yours. An employee or hacker could point your domain elsewhere. It’s like the fine print: final interpretation rights belong to the DNS provider.

IP and Servers

Finally, put your website code and data on a server so the domain can point to it via DNS. Let’s assume a simple website with one server.

Rent a server from a cloud provider (Alibaba Cloud, Tencent Cloud). Servers have monthly bills based on disk space, data sent, etc.

Once the server is set up, you’ll have its IP address. Use DNS to point your domain to it. Your website is now public.

Since the server is rented, you only have usage rights. The cloud provider can shut it down or delete its contents.

Alternatively, buy a server and put it in your office. A company I worked for did this. The server and contents are completely under your control. But this needs a high-quality network. Small websites usually don’t do this.

The New Tech Explained

That’s the traditional web. Now, let’s explore the new technology.

ENS

As mentioned, ICANN controls top-level domains. But many teams challenge this. They believe domains are internet infrastructure, concerning everyone, and shouldn’t be controlled by a centralized organization – not even a non-profit. They advocate blockchain smart contracts to manage domains (top-level, main, subdomains). This ensures open, transparent, and trustworthy management.

Four main blockchain projects provide domain services: HandShake (HNS), DecentraWeb (DWEB), Ethereum Name Service (ENS), and Unstoppable Domains. The first two offer top-level domain registration/trading; the latter two control some top-level domains and offer main domain registration.

The blockchain world has strange top-level domains: .x, .eth, .coin, .wallet, .888, even emojis. These bypass ICANN. Control and ownership are recorded on the blockchain, operating by smart contract rules, not controlled by the founding teams.

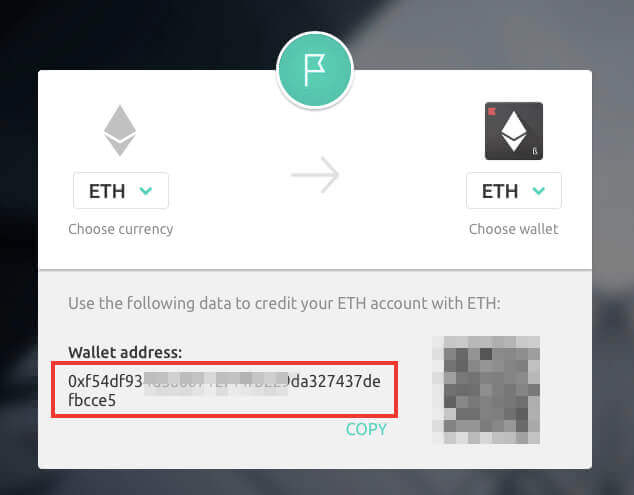

My domain (victor42.eth) is from ENS, an Ethereum-based service where domains end in .eth. After purchase, a smart contract records on Ethereum: “victor42.eth belongs to wallet xxxxxxxxx for 20 years.” This is recognized and protected by Ethereum. xxxxxxxxx is my Ethereum wallet address.

ENS also provides domain resolution. In the blockchain world, DNS isn’t strictly necessary. On the traditional web, DNS providers ensure security, preventing tampering. But the blockchain is inherently secure. Domain resolution becomes simpler, a feature domain service providers can easily add.

With this domain, no one can transfer it or point it elsewhere during the usage period, not even Vitalik, Ethereum’s founder. After the period, if I don’t renew, the smart contract reclaims it.

What’s the difference between blockchain and traditional domains? Let’s compare the traditional web and blockchain.

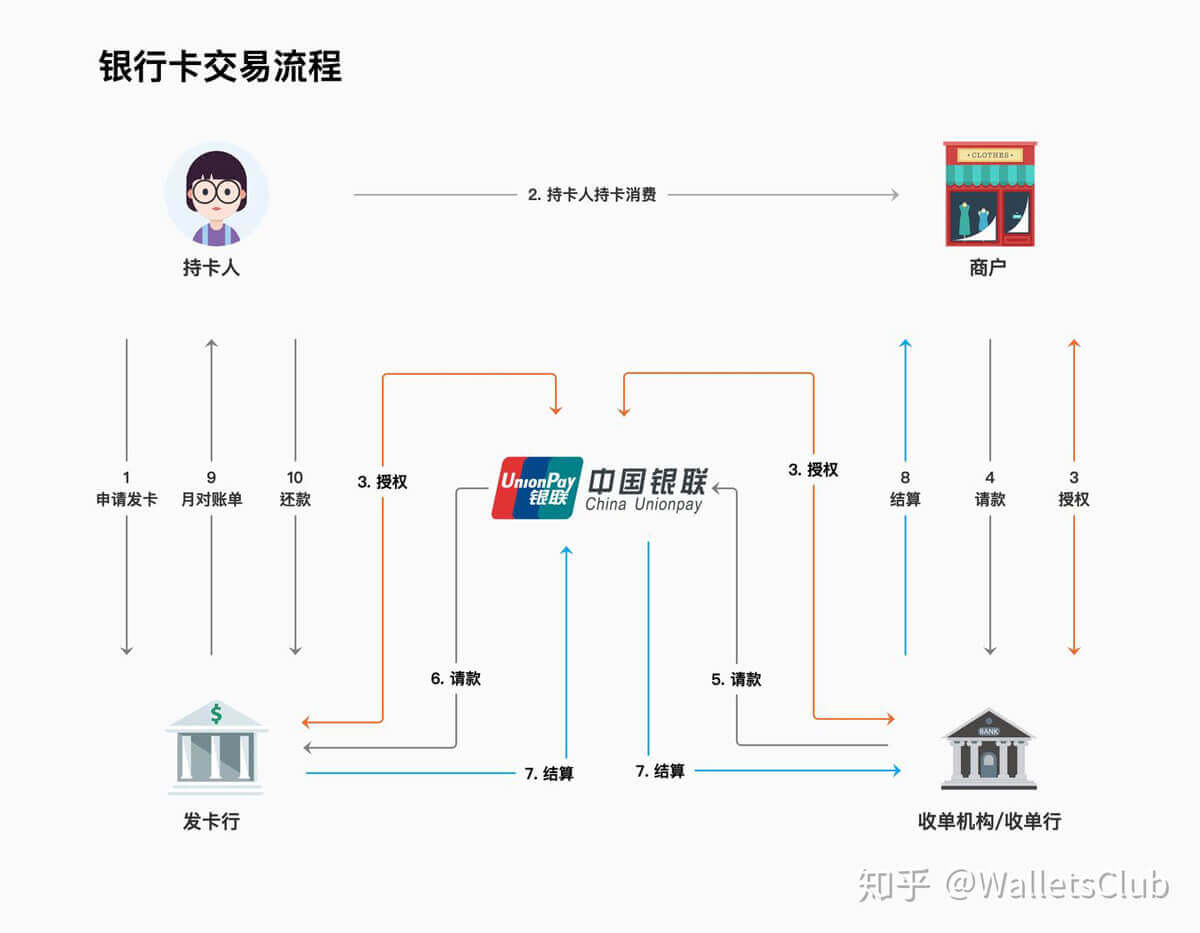

The traditional web transmits information. Domains are nicknames for content. WeChat Pay transmits monetary value as information, requiring UnionPay to verify it.

The blockchain network transmits value. It’s an economic system using cryptography, verifying value transfer itself. Wallet accounts are the infrastructure. Domains nickname wallet addresses. Pointing to content is an additional function.

An Ethereum wallet address is hard to remember. That’s why it needs a domain.

Blockchain domains can point to a wallet and content. Entering the domain during a transfer sends it to the wallet; opening it in a browser displays the content.

IPFS

The previous section covered blockchain domains, which I now own and can point to a website. The next step is finding a decentralized hosting solution.

I’ll detail the specifics later. This section explains IPFS’s technical principles. It works differently than the usual C drive, folder, subfolder structure.

If you’re able, check out this video first (it’s more intuitive than my explanation): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Uj6uR3fp-U.

Despite the “IP” in its name, IPFS is unrelated to traditional IP addresses. It stands for InterPlanetary File System. Crucially, if anyone on the IPFS network deems content valuable and keeps it, no one can delete or stop its spread.

This might seem commonplace. Isn’t the traditional web similar? If a Weibo account posts something inappropriate, even after deletion, screenshots can ensure it’s not forgotten. That’s the internet’s open spirit.

However, PR exists. Most content spreads on major platforms. If these platforms cooperate to remove content, widespread dissemination stops. PR can’t erase content globally, but it can make it invisible to most. You can still copy it to a USB, but those unaware won’t know where to find it.

But, how do pirated movies spread? Studios can’t stop them, right? Exactly. Pirated movies use distributed networks, not just the traditional web.

Downloading with Xunlei requires a BT torrent file. Xunlei uses the torrent, showing seed count. More seeds mean faster downloads; no seeds mean no download. Each seed is a device storing the content, often other downloaders. You’re not downloading from a server, but from other seeds. Blocking content requires finding and destroying all seeds – practically impossible.

IPFS uses this for file transfer, but also as a storage method. How does the network know each seed has the same movie, given different versions (full, cut, original audio, dubbed)?

The answer: content separation at the file level. Different BT torrents mean different versions. This uses a hash algorithm, encrypting any content into a fixed-length string, like:

23db6982caef9e9152f1a5b2589e6ca3

Download sites often show a file’s MD5 code (a type of hash algorithm) to verify against tampering or viruses after download.

Hash algorithms have a key feature: identical content, using the same algorithm, always produces the same result, regardless of time or location. Even a tiny change (e.g., a Chinese period to an English one) drastically alters the resulting code. This one-to-one correspondence means hash algorithms provide a unique ID for any content, like a social security number.

This makes IPFS efficient. Content is distributed via its hash code. Displaying it requires retrieving the entire content from the IPFS network.

For example, NFT digital collectibles. Ownership is recorded on the blockchain (“Content xxxxxx belongs to so-and-so”). A collectible can be large (image, music, video). How can a blockchain, with small blocks, store this? It stores the hash code, uniquely identifying the content, confirming ownership. ENS domains are also NFTs, but with practical uses beyond viewing.

IPFS builds its storage on this. Unlike traditional storage (retrieving by location, like sending a package to a specific address), IPFS retrieves by content. Knowing the content (its hash code ID) is enough. You request “content 23db6982caef9e9152f1a5b2589e6ca3,” and IPFS finds and delivers it from the closest source.

This has advantages:

- Reliability: Any device with the content can transmit it. Even if major data centers are destroyed, you can still download from a neighbor via IPFS, as long as the network is up.

- Speed: It finds the closest source, ensuring fast transmission, like BT seed downloads.

- Resource Saving: On the traditional web, the same video posted on multiple platforms (WeChat, Weibo, TikTok) is stored multiple times. IPFS theoretically needs only minimal server backups, with most storage and transmission through personal devices.

- Tamper-proof: Each piece of content has a unique code. Tampering creates a new code. The original code always leads to the original content, making it ideal for recording information age history, avoiding the digital dark age.

Disadvantages:

- Unpopular content may be harder to access if few devices store it and are offline. However, uploaders can keep important content online.

- IPFS is open; it can’t store private data. It’s unsuitable for personal cloud drives. Posted content is publicly visible.

- Think before posting; there’s no going back. Changes generate new content, not overwrites.

- Version fragmentation: Updates create new versions. Identifying the latest is addressed later.

The name “InterPlanetary File System” isn’t just hype. If we colonize Mars, how will information transfer? Earth-Mars distance varies. Communication can take 4-24 minutes one-way, or be impossible during solar conjunction (like Tianwen-1).

With the traditional web, a Martian accessing Wikipedia on Earth would face 8+ minute delays per page.

Why not store Wikipedia’s data on Mars? Martian colonization will be gradual. Earth’s internet holds vast data. Copying everything is impractical. Only important data would be prioritized; less important data (like Basque) would remain on Earth.

With IPFS, the first Martian accessing Basque still faces the delay (blame Einstein, not me). But subsequent Martians can access it directly from the first user’s device, quickly. If that first user is a linguistics professor who deems it important, they can put it on a Martian IPFS server, establishing Basque data on Mars.

IPFS itself isn’t a blockchain; it’s a network like BT downloads. The IPFS team created Filecoin, a blockchain using cryptocurrency to reward users for providing storage, maintaining IPFS and improving reliability. I won’t detail that. IPFS is crucial for the blockchain world, less so for the traditional web, so I consider it part of the former. Calling websites on IPFS “blockchain websites” isn’t perfectly accurate, but it’s simpler.

IPNS

ENS handles domain + DNS, IPFS handles IP + server. Ready to build a blockchain website? Not quite. There’s a key issue, unique to IPFS.

Traditional storage updates by replacing content at a location. IPFS finds content via hash codes. Updates create new content; the old hash code remains. How do users see the latest version of a constantly updated website? Announcing new hash codes constantly is impractical.

IPFS has a built-in mechanism, IPNS (InterPlanetary Name System), similar to DNS. The “NS” is the same. It’s like a hash code, but points to different content without changing itself. Associating IPNS with IPFS content makes IPNS automatically point to the new version’s hash code after updates, like a traditional URL.

ENS domains can point to IPNS, connecting everything. The website access process is entirely within the blockchain world:

ENS domain -> ENS points to -> IPNS -> Latest IPFS content -> Website

Putting the New Tech into Practice

Theory is done, now for practice, which is simple.

The blockchain world has evolved beyond speculation. Many practical applications are building the next-generation network infrastructure. You can use existing applications for deployment, which is convenient.

Blockchain Domains

Domains and storage are separate. Blockchain domains can point to traditional websites, and traditional domains can point to blockchain websites. A blockchain domain isn’t mandatory.

This is likely the only part requiring money. You buy a domain on ENS using Ether. Cryptocurrency trading regulations in mainland China might be a hurdle. But if you’re this far, you’ve likely bought crypto before.

If not, wait. Understand cryptocurrency wallets (accounts, transfers) before buying. Don’t use shady exchanges. Lack of understanding can lead to financial loss.

Once you understand, you’ll know how and where to buy. Bypassing the firewall and using Google is prerequisite. It’s hard to navigate within the Chinese internet.

The purchase is similar to traditional domains; no step-by-step tutorial is needed. You’ll have an Ethereum wallet with a .eth domain. Leave extra Ether for transaction fees during domain pointing setup.

Fleek

Fleek handles everything else: deploying websites on IPFS and domain pointing. It’s free for personal websites with low traffic.

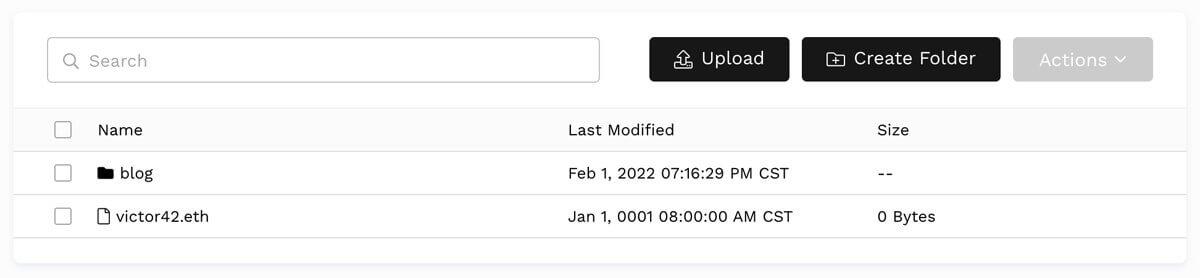

Fleek has two upload methods. “Storage” is like Baidu Netdisk. Upload a file, get an IPFS-stored link:

This is for sharing individual files, not domain binding. I use it for image hosting in blog posts.

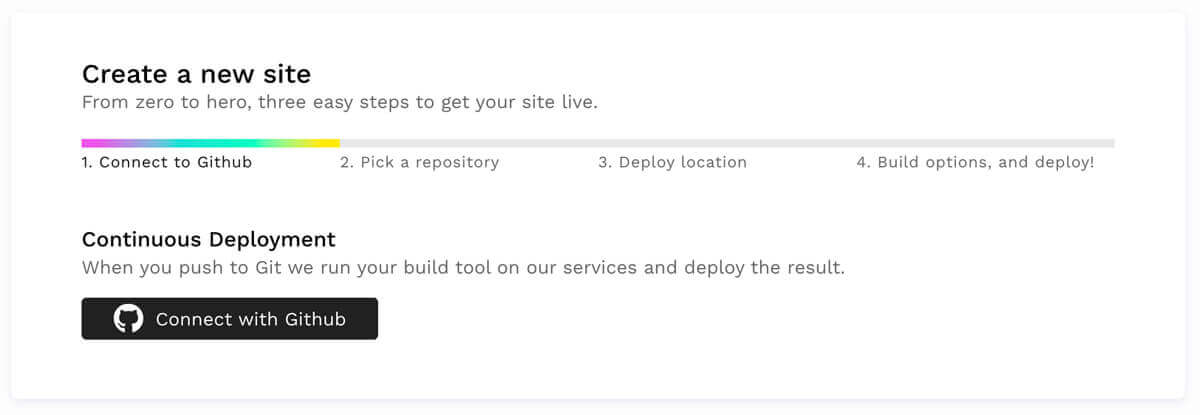

“Hosting” links to your GitHub account, reading code from a repository.

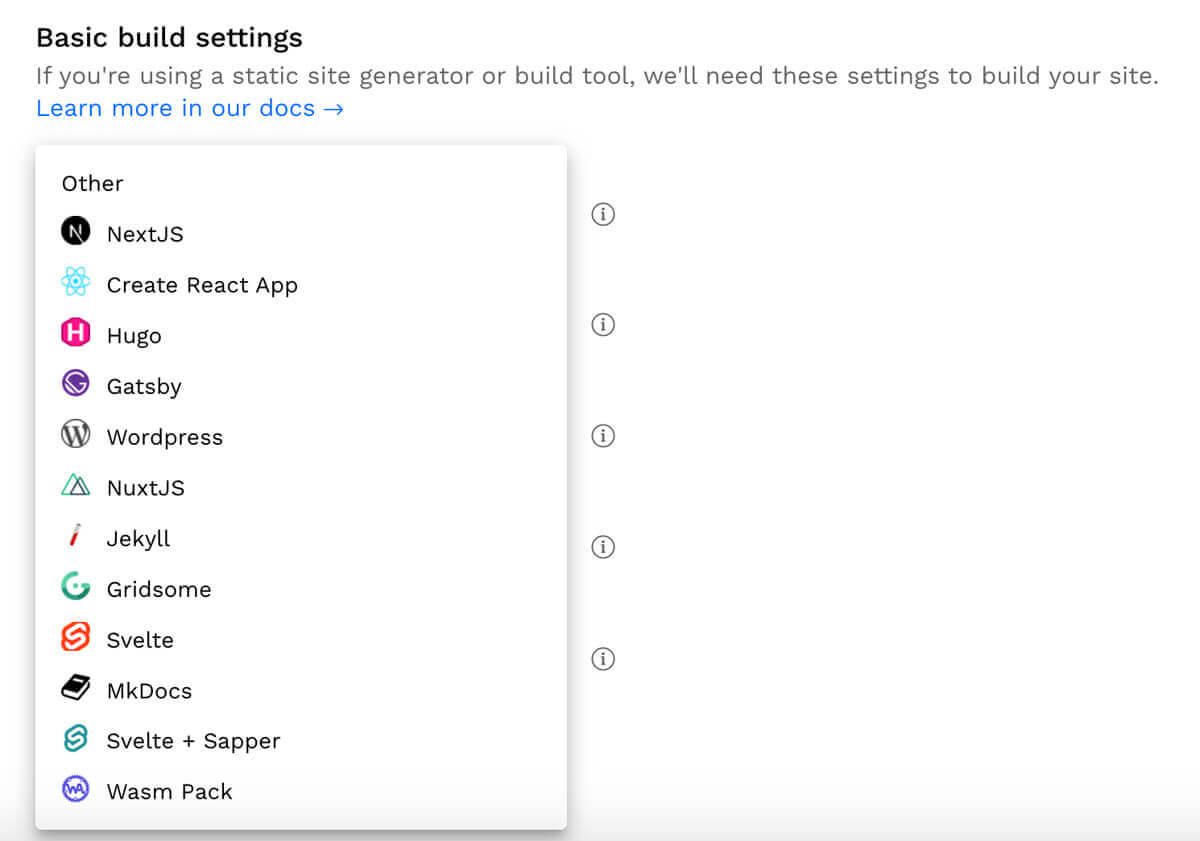

Then choose your static website system.

My previous blog used Hexo, a good system. But its creators and users are mainly Chinese-speaking, with low international recognition. Fleek, an overseas product, doesn’t support Hexo. I chose Hugo, rebuilt a blog on GitHub, and moved content. Hugo is also excellent. Research building websites with Hugo; it’s not blockchain-specific.

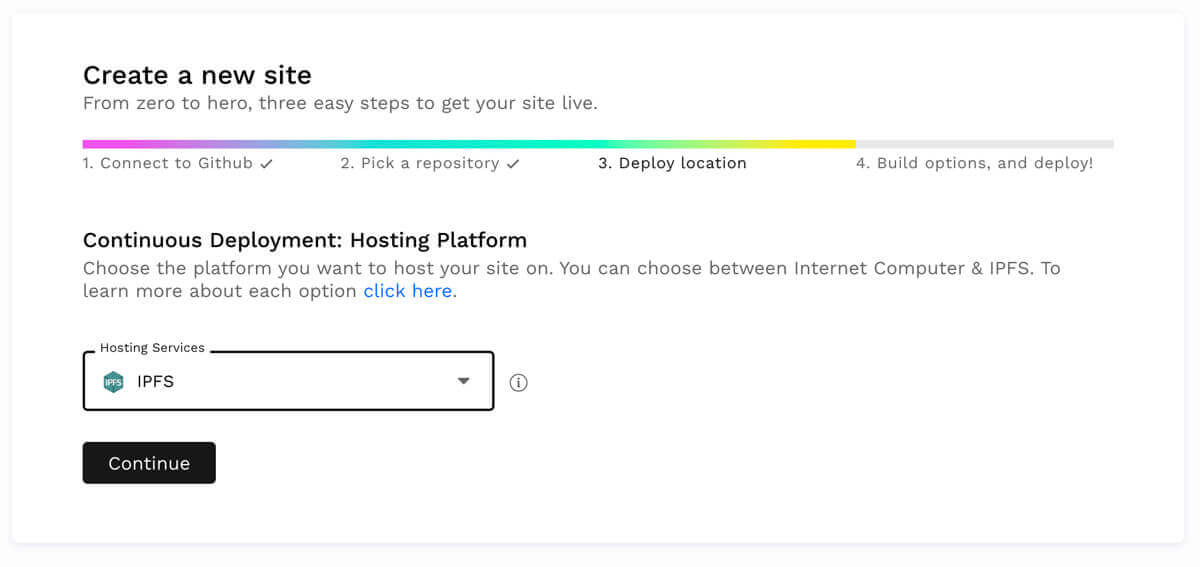

Next, choose the deployment network. The default is IPFS.

“Internet Computer” is another option, a different blockchain for deploying services, with its own pros and cons. It’s newer and more isolated. I tried it; it’s interesting.

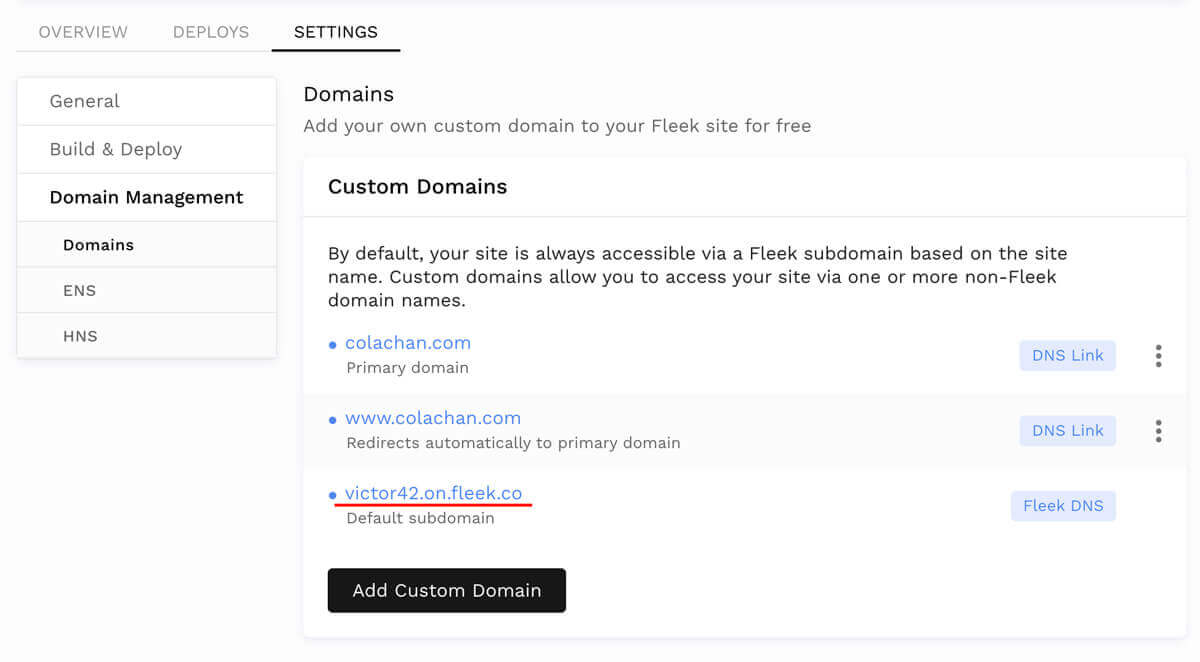

After these steps, the website deploys quickly. Fleek grabs content from GitHub, deploys on IPFS, and provides a subdomain. Your blockchain website is accessible.

Domain pointing is done in Fleek’s Domain Management. For traditional domains, it guides you on filling resolution records with your domain/DNS provider. For ENS domains, follow its instructions; it requires your Ethereum wallet and a small Ether fee.

You can also add HNS domains (a blockchain top-level domain provider). Ownership is recorded on the Bitcoin blockchain, obtainable via auction on Namebase with Bitcoin. You need to generate a main domain after getting the top-level domain. I haven’t tried this.

eth.limo

Your blockchain website is set up: domain, IPFS deployment, domain pointing. But with a blockchain domain, typing xxxx.eth into a browser won’t work.

This isn’t the blockchain’s fault. Most browsers are from the traditional web era, recognizing only ICANN-approved protocols/domains. Non-HTTP protocols or domains not on ICANN’s list won’t open. There’s a gap.

eth.limo bridges this gap. Add .limo to your domain (e.g., https://victor42.eth.limo/) for any browser. Blockchain-supporting browsers (like Brave) can open it without .limo. But you can’t assume all visitors have these.

It’s a creative solution. What does eth.limo do?

victor42.eth and victor42.eth.limo are fundamentally different. victor42.eth uses .eth as the top-level domain; I own the main domain victor42. victor42.eth.limo uses .limo as the top-level domain; eth.limo is the main domain (not mine); victor42 is my subdomain.

eth.limo’s servers access the blockchain world. Accessing their subdomain, they cross the bridge, package the website’s content, and deliver it.

This diagram explains. The rows: traditional website, traditional domain + blockchain website, blockchain domain + blockchain website.

- DNS points the domain to the server, opening the website.

- DNS points the domain to Fleek’s server; Fleek finds content on IPFS, opening the website.

- Accessing the traditional domain, the delivery person accesses the blockchain domain, pointing to IPFS content, opening the website.

Red/blue lines: the traditional web/blockchain network border. Crossing it enters a new world.

eth.limo isn’t unique. eth.link is more widely used, with a more normal-looking domain name.

Limo refers to this. It’s still weird.

I initially used eth.link (by Cloudflare). It’s centralized, using Cloudflare’s servers. As an overseas product, it had issues in China, occasionally going down. eth.limo uses multiple servers, with multiple bridges, preventing access failures at the last mile.

Conclusion

That’s all.

ENS and IPFS show a world where new technologies are thriving. They remind us to keep exploring.