Target audience: English learners, data analysis enthusiasts, Python coders, and my friends.

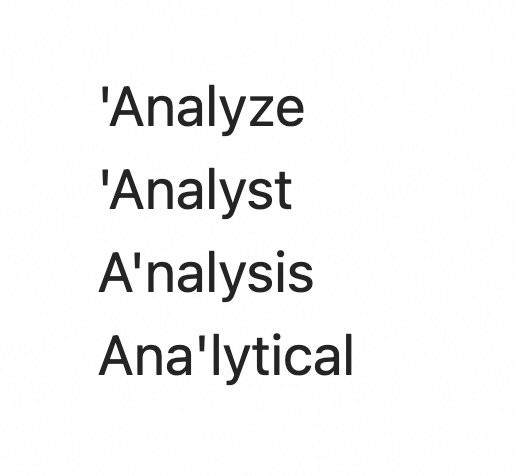

This is my first data analysis project. I’ve been teaching myself data science for over a year, picking up skills along the way, but I hadn’t tackled a real-world project. During my studies, the words ‘analyze,’ ‘analysis,’ and ‘analytical’ kept appearing. The stress placement is unpredictable (‘analyze, a’nalysis, ana’lytical) – a real headache! It turned reading into a tongue-twisting exercise.

Some claim there are rules for stress, but they’re often lengthy and complex. Others say there are too many exceptions. However, even with those three words, a pattern does emerge. English seems to avoid three unstressed syllables in a row and tends to place stress near the beginning. For words with five or fewer syllables, the stress often lands on the antepenultimate (third-to-last) syllable.

It makes sense, doesn’t it? Three unstressed syllables in a row would be monotonous. Stress adds rhythm. It’s like driving on a straight road – you’ll likely doze off. Placing stress too late would also hinder comprehension. Imagine a long word with emphasis on the very last syllable – you’d likely miss the meaning!

To illustrate, consider Mandarin Chinese. It has a significant flaw: the word “不” (bù, “not”). Both the consonant and vowel are faint, especially in rapid speech. The vowel becomes even weaker. You often can’t discern if someone even uttered “不”! This creates a major communication problem, as it distinguishes between two opposite meanings. When my daughter cries, I struggle to understand if she’s saying “要” (yào, “want”) or “不要” (bù yào, “don’t want”).

Back to English stress. My theory seemed reasonable, but I needed evidence. As a data-science novice, I decided to get my hands dirty and see how many words actually followed this pattern.

Research Plan

Having learned data analysis, the research plan formed quickly. It involved collecting, cleaning, analyzing, and visualizing data. Regression analysis or prediction wasn’t necessary.

Here’s the skillset I had, which was sufficient:

- Find a comprehensive word list.

- Find a free, batch method for obtaining phonetic transcriptions from an online dictionary.

- Determine the syllable count and stress position for each word (possibly with AI assistance).

- Analyze the distribution of stress positions and visualize the findings.

- Test my hypothesis.

Let’s dive in.

Data Source

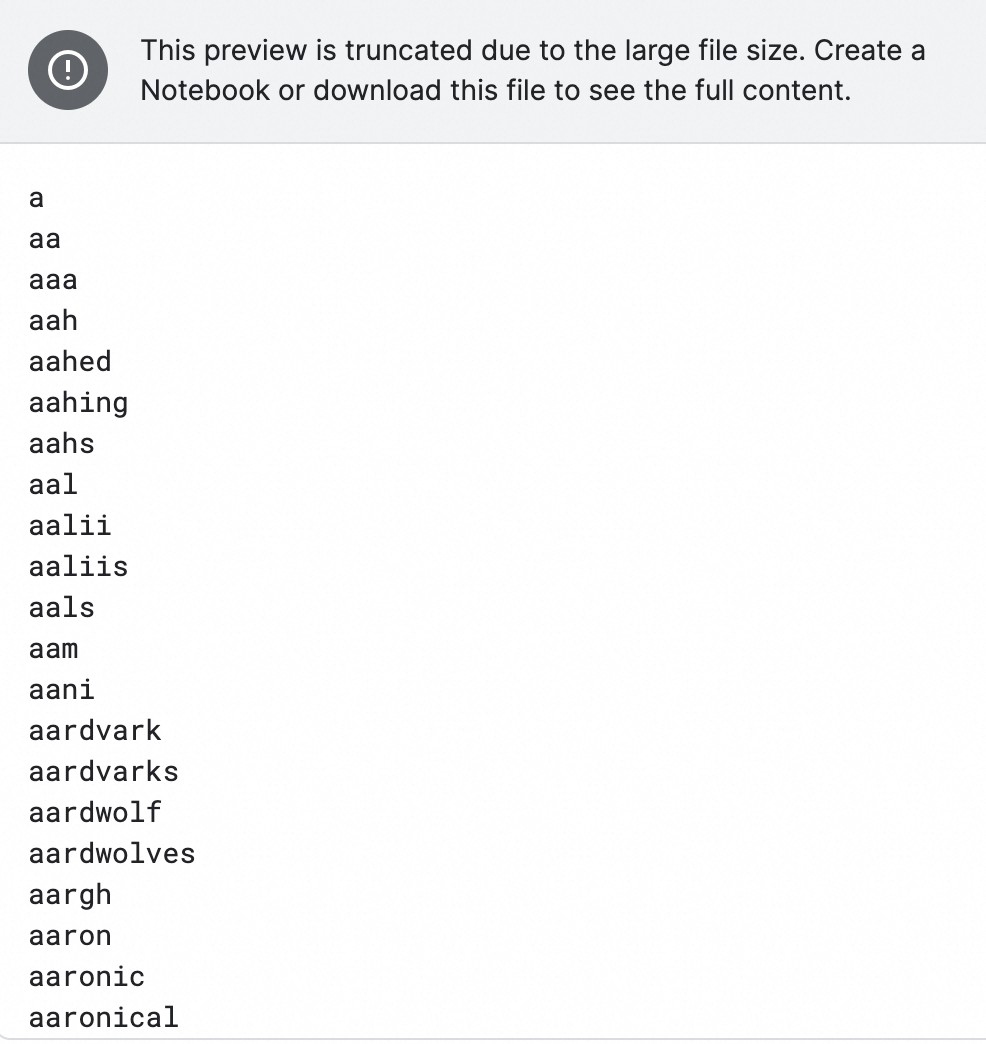

I found a dataset on Kaggle, a popular data science community. It’s a simple .txt file containing over 300,000 English words, listed alphabetically, one per line:

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/bwandowando/479k-english-words

The .txt file is 4MB, comparable to a million-word novel.

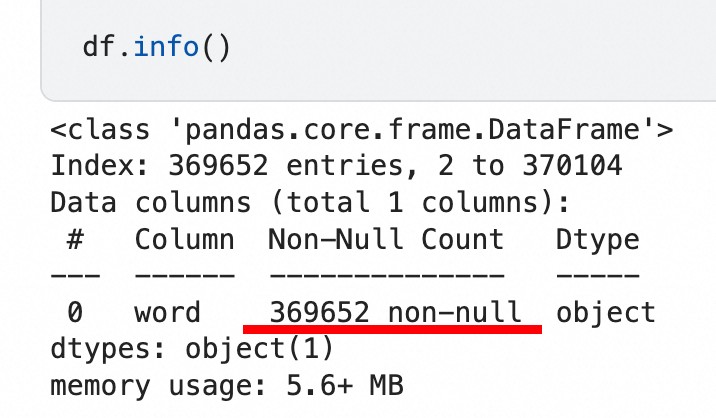

I created a Kaggle code project, imported the dataset, read all the words, and obtained a table with 369,652 rows and 1 column.

Getting the Pronunciation

The table only contained words. For rigorous research, I needed phonetic transcriptions.

Fortunately, I discovered a free online dictionary API: https://dictionaryapi.dev/.

Now, I had to look up each of those 300,000+ words. Naturally, I’d write code to automate this.

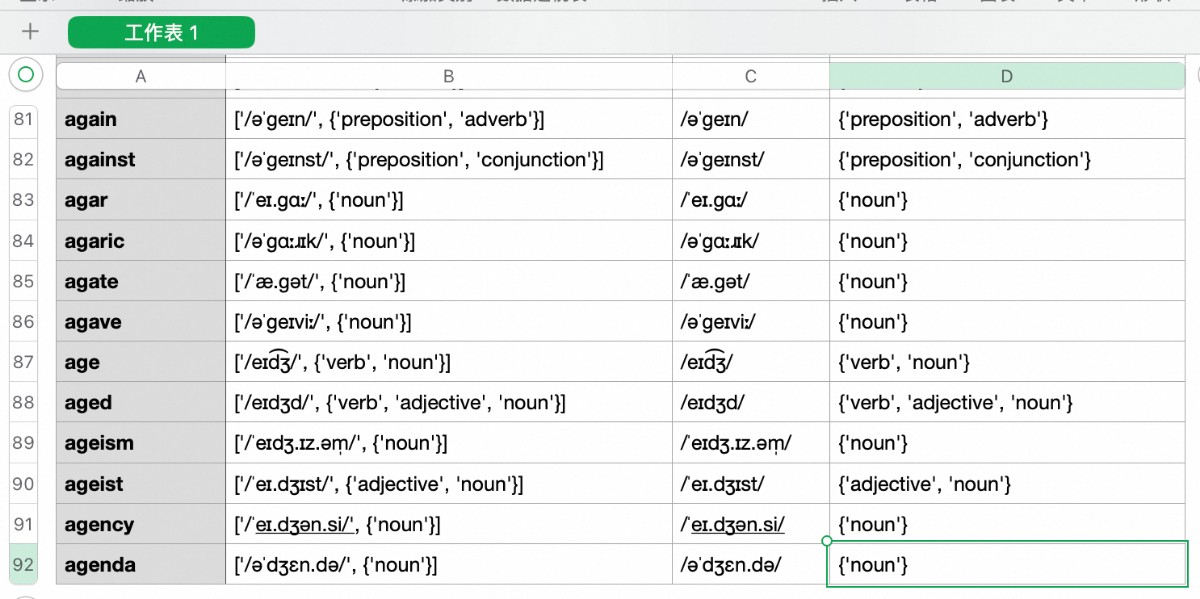

The API returned more than just phonetics; it included audio, etymology, parts of speech, meanings, and examples. The useful components were the phonetics, etymology, and part of speech. However, etymology was mostly missing, so I extracted only the phonetics and part of speech.

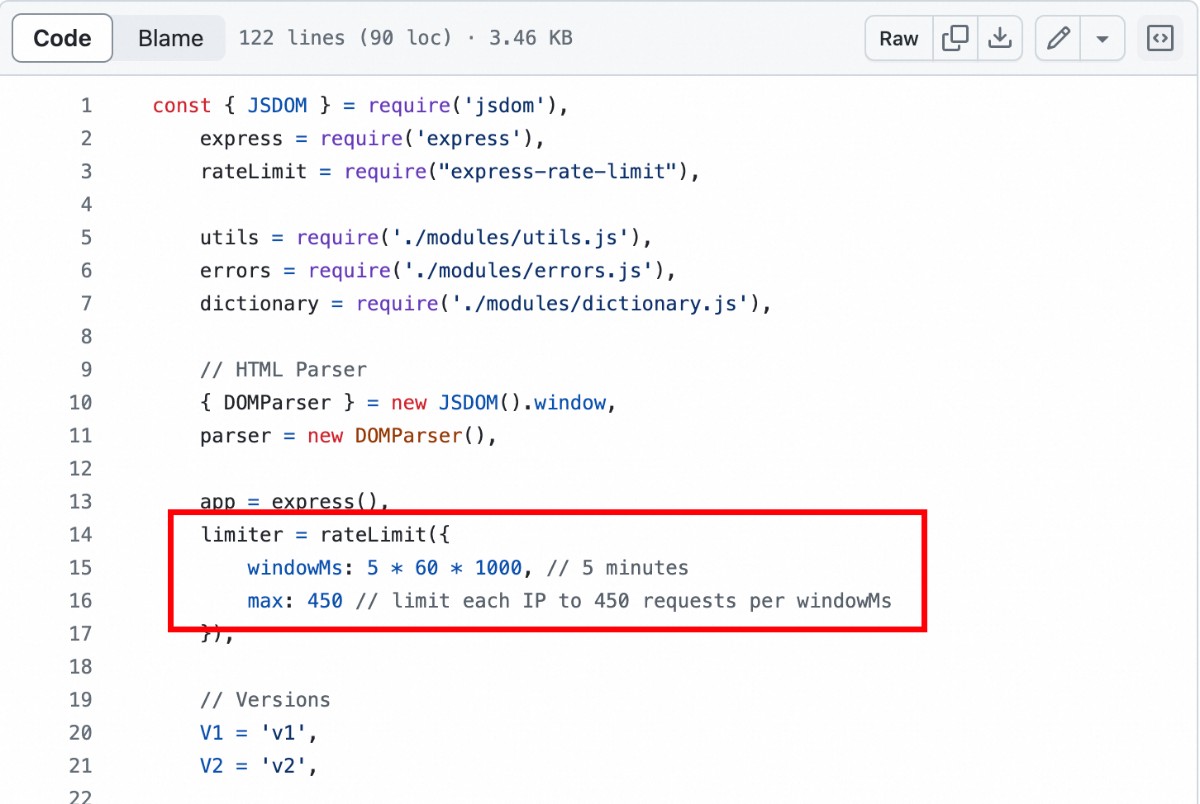

The sheer data volume posed a challenge. The API documentation didn’t specify request limits, but I found it in their Github code: 450 requests every 5 minutes. For 369,652 words, even non-stop, it would take 369652 / 450 * 5 / 60 = 68.45 hours – almost 3 days!

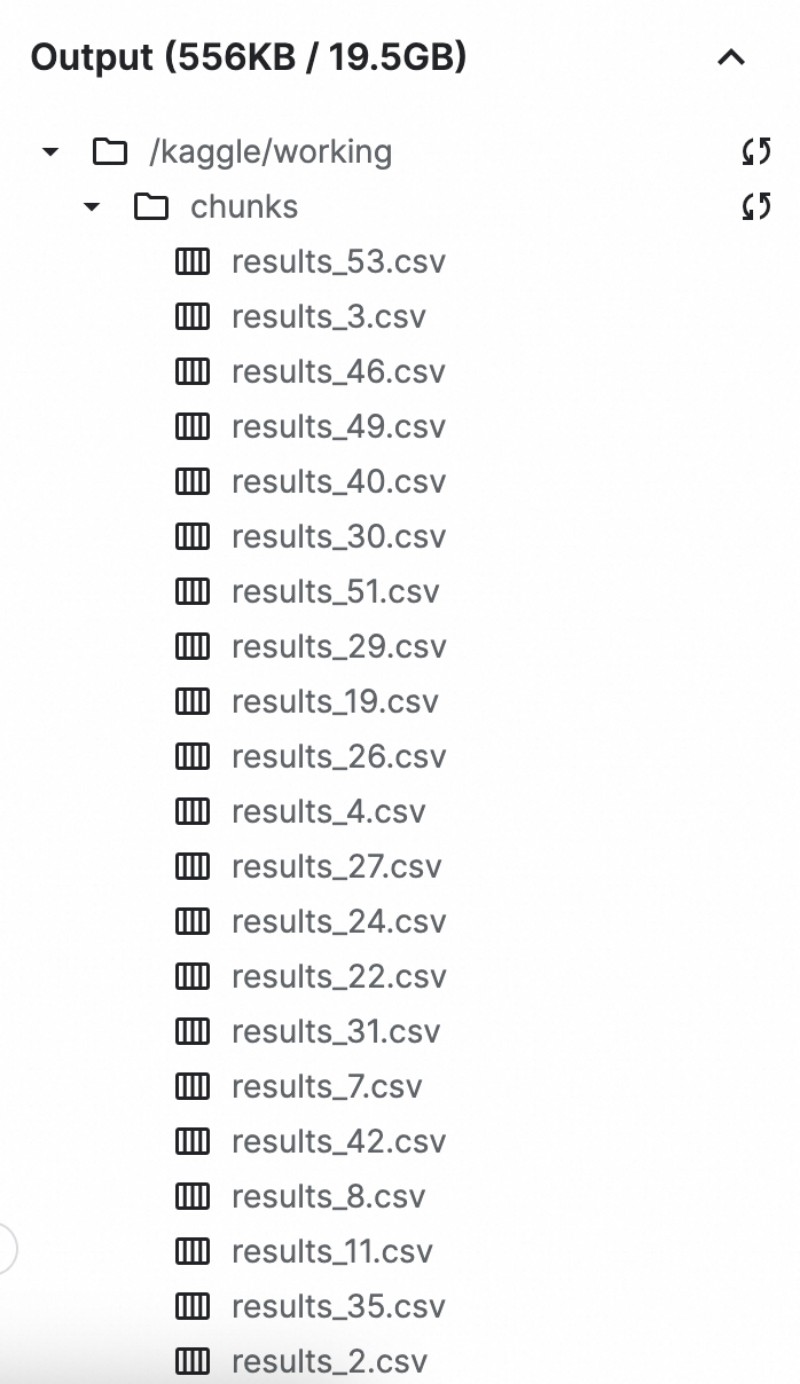

Alright, three days it was. But I had to adjust my strategy. I added a function to chunk queries and save results periodically. Every 1,000 rows, I’d save to a sequentially numbered file. I’d then continue querying based on the sequence number. Finally, I’d merge all 300+ files.

It turned out that most of the 300,000+ words were obscure and not found in the API. I only got results for roughly 100 out of every 1,000 words. The file above contains only 92 rows.

Linguistic research indicates that 3,000 English words cover 95% of everyday usage, and 1,000 cover 89%. Another study shows that the average adult has an active vocabulary of about 20,000 words and a passive one of 40,000. Thus, only about 1/10 of the dataset is relevant, which is reasonable.

Data Cleaning

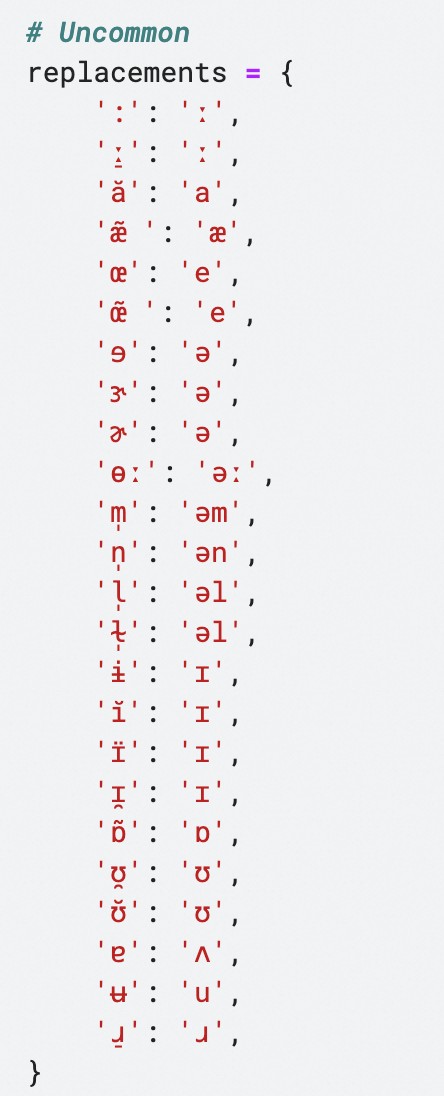

After merging, I found the dictionary’s phonetic symbols were inconsistent, containing uncommon symbols like ɘ, ɝ, ɚ, ɨ, ʉ. These represent subtle pronunciation variations, roughly equivalent to standard sounds. I had to replace them; otherwise, they’d disrupt syllable counting and subsequent analysis.

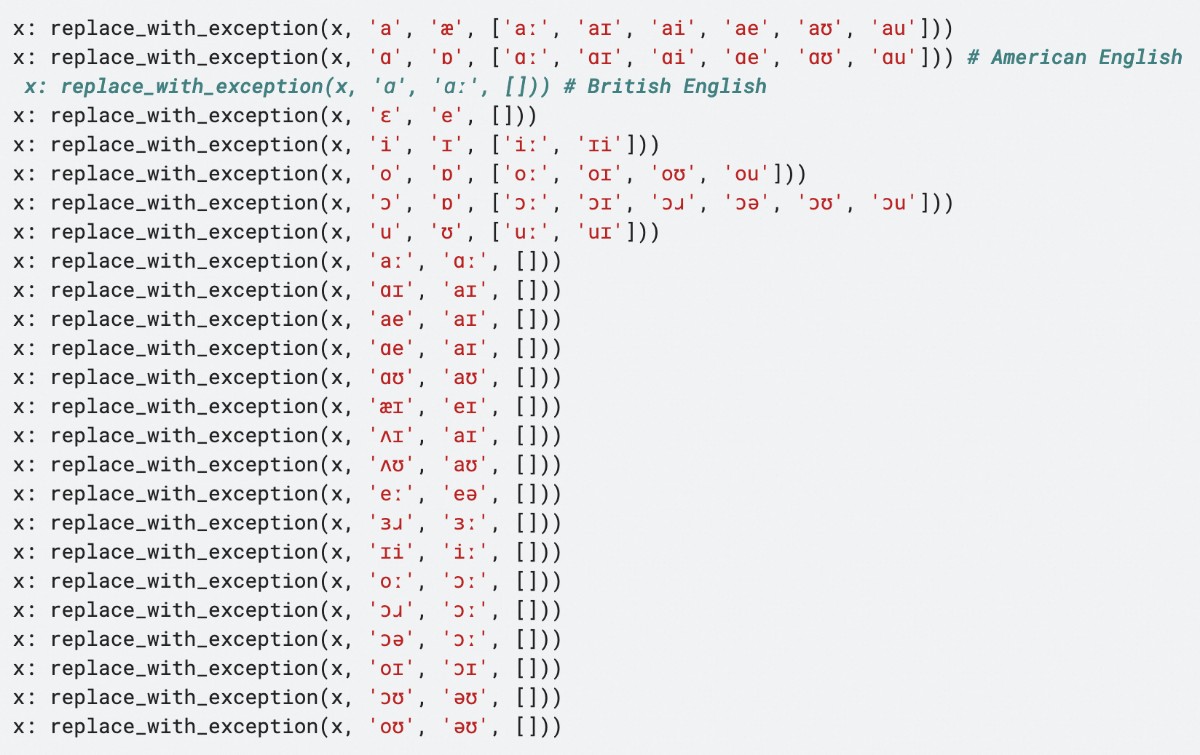

Besides unusual symbols, there were many phonetically identical but differently written symbols, like əu/əʊ and ai/aɪ. These also required merging. Each line in the image signifies replacing the first symbol with the second, leaving bracketed symbols untouched.

Some words differ significantly between British and American English. I prioritized American English conventions.

Numerous unconventional spellings existed. Over- or under-replacement could easily cause phonetic errors. I wrote a temporary checker, manually consulted the Cambridge Dictionary, and refined my replacements. This took time.

After processing, the vowel symbols were cleaner. For “anthropomorphic”:

- Before:

[ˌæ̃n̪θɹ̠əpəˈmɔɹ̠fɪ̈k] - After:

[ˌæn̪θɹ̠əpəˈmɔːfɪk]

I didn’t handle consonant symbols, as they were irrelevant to my goal, and that’s a more complex issue.

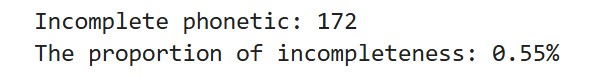

Later, I discovered some inaccuracies in the dictionary API. For instance, “abacus” was transcribed as /-saɪ/? Nonsense! The information was incomplete.

I calculated this occurred in 0.55% of all words – a small fraction. The incomplete transcriptions seemed random, lacking commonality, so I filtered them out. I’m now analyzing a sample, not the complete data. However, the sample is large enough to be representative, allowing the research to proceed.

Analyzing Phonetic Transcriptions (AI)

This step entails counting syllables from phonetic transcriptions and identifying the stressed syllable using the ˈ mark.

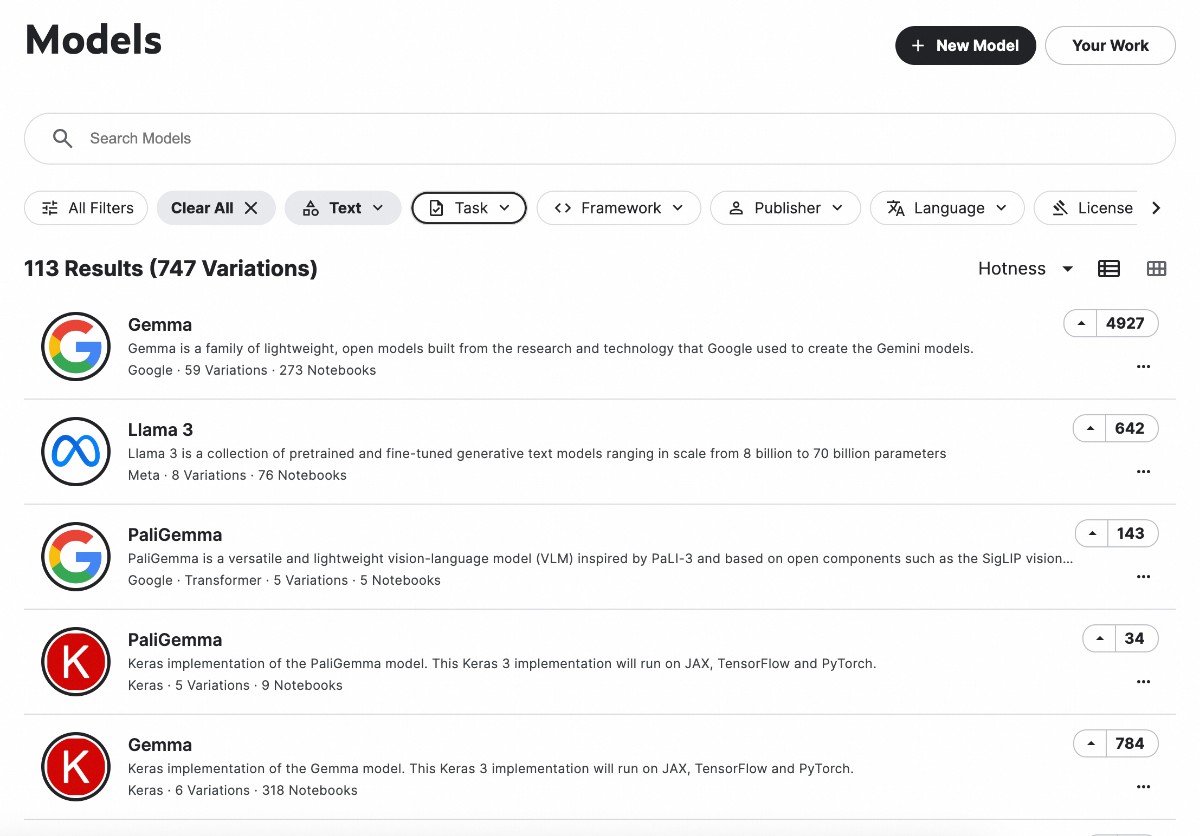

I aimed for a shortcut by deploying an AI model on Kaggle. AI should excel at language, right?

I tested several text-based models but encountered obstacles:

- Large models wouldn’t run: Among Kaggle’s deployable open-source models, Llama3 70b could accurately determine syllable count and stress position. ChatGPT, Claude, and even GPT-3.5 could also do it. Language seems to be a strength of large language models. The issue? Kaggle’s free tier can’t run such large models.

- Small models were inadequate: Kaggle’s two free T4 GPUs can handle smaller 7b models like Llama3 8b, Gemma 7b, and Qwen2 7b. However, these smaller models, on Kaggle or elsewhere, couldn’t reliably perform the task.

I refined prompts, guiding the AI step-by-step, and provided examples:

<task>

your task is to count how many syllables there are in an English word. list them all then count. finally answer which syllable the stress falls on(tell me the number). answer **EXACTLY** in the example format.

<example>

word: analysis

phonetic transcription: /əˈnælɪsɪs/

syllables:

1. ə

2. 'næ

3. lɪ

4. sɪs

syllables count: 4

stress position: 2

final conclusion: <<<2/4>>>

<word>

analytical /æn.əˈlɪt.ə.kəl/

But the smaller models kept failing. Perhaps they weren’t capable. Phonetic symbols are vastly different from standard English letters, almost a separate, niche language for AI.

This experience highlighted a key point: these open-source small models cluster around 7 billion parameters likely because that’s the upper limit for running on specific GPUs. In this era of constrained computing, GPUs dictate the scale.

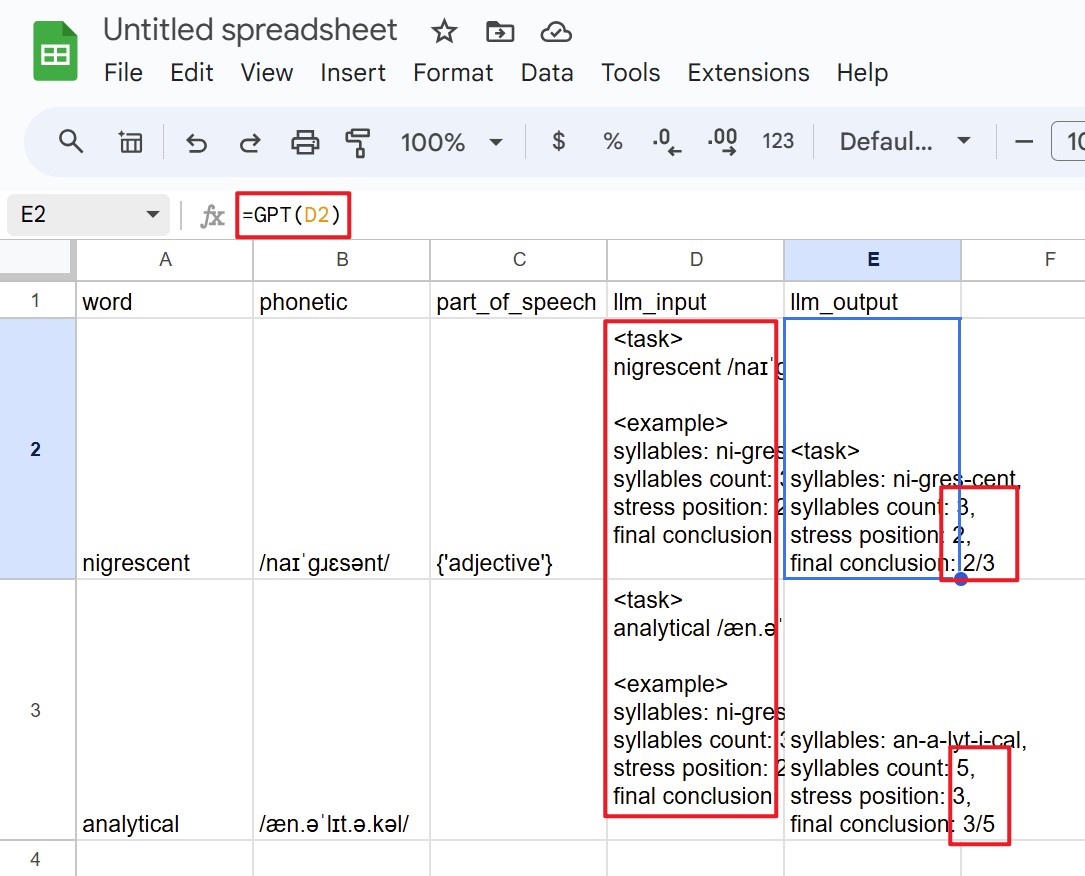

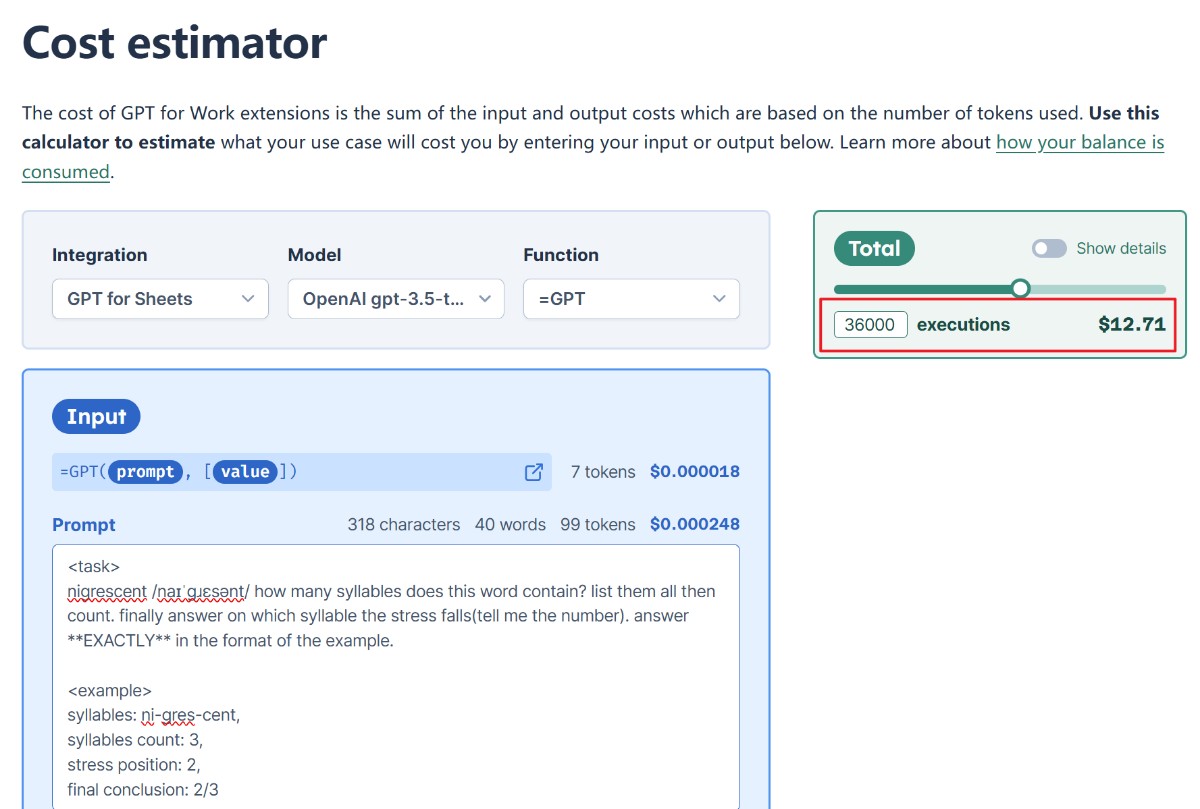

Was AI a dead end? I then considered a workaround: Google Sheets with an AI plugin. I could input the phonetic data into Sheets, write a prompt in the adjacent cell (including the word and transcription), and use a formula from an AI plugin to generate the result. This plugin, powered by GPT-3.5, could handle the task. The classic Excel drag-down trick would then populate the entire column.

The plugin’s pricing was reasonable, around 90 RMB for my data volume. However, I was unsure if it could handle tens of thousands of AI generations simultaneously. Debugging and regenerating could double the cost, making it risky.

Analyzing Phonetic Transcriptions (Algorithm)

Okay, no more AI—I’d handle it myself. Counting syllables and locating stress? An algorithm could do that, and more reliably. Here’s the approach, using analytical /æn.əˈlɪt.ə.kəl/ as an example:

- Create a set of all vowels:

ɑaæɒʌəɛeɪiɔoʊuʉɜ - Remove slashes, parentheses, spaces, and dots:

/æn.əˈlɪt.ə.kəl/becomesænəˈlɪtəkəl - Iterate through

ænəˈlɪtəkəl, checking against the vowel set. Counting vowels:æ,ə,ɪ,ə,əyields 5 syllables. - Split by the stress mark

ˈ:ænəˈlɪtəkəlbecomesænəandlɪtəkəl. Use the first part,ænə. - Count vowels in

ænəas in step 3: 2 vowels. - Add 1 to get the stress position: the 3rd syllable.

The logic was clear, so I had AI write the code—a trivial task for it. A few tweaks, and it worked.

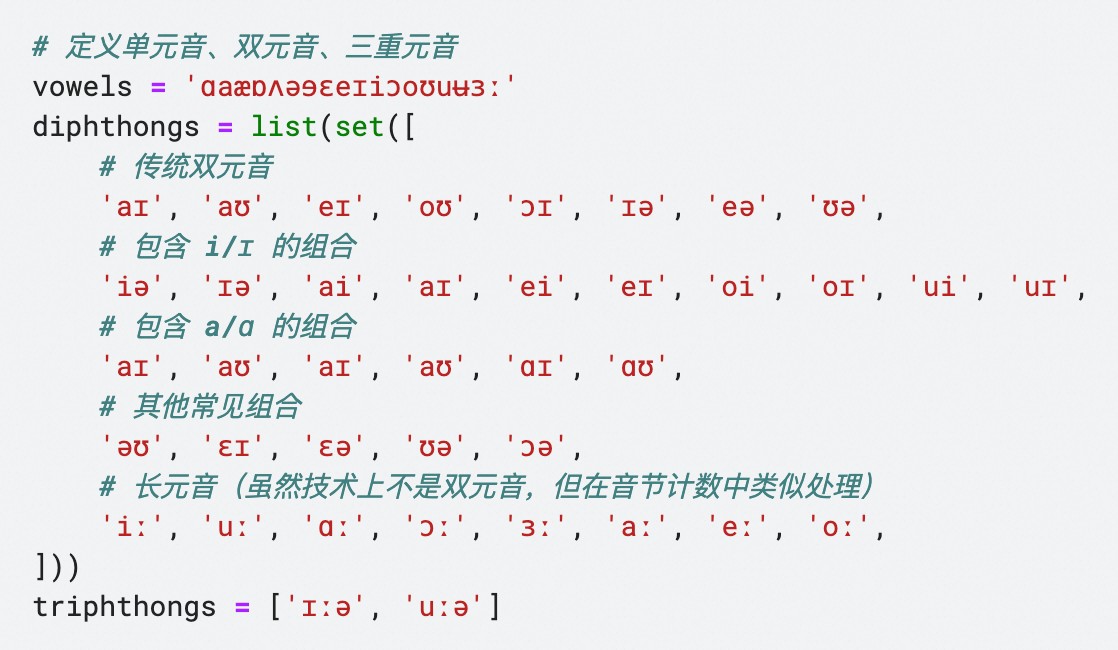

A challenge arose in step 3: diphthongs, triphthongs, and long vowels. For ei, the algorithm would count e and i (2 syllables), but ei as a diphthong is only one. Triphthongs would be counted as 3.

The algorithm needed adjustment. I created three vowel sets: monophthongs, diphthongs, and triphthongs. The vowel check now involved three passes:

- First pass: Check each character against the monophthong set. This overcounts diphthongs and triphthongs.

- Second pass: Check two characters at a time against the diphthong set. If found, subtract 1 from the syllable count. Importantly, skip the next character after a diphthong to avoid miscounting triphthongs like

aɪəasaɪandɪə. - Third pass: Check three characters at a time against the triphthong set, subtracting 1 if found.

This refined algorithm accurately counted syllables. (Note: I treated the long vowel marker ː as a phonetic character; iː, ɑː are handled as diphthongs, iːə, uːə as triphthongs, which doesn’t affect the outcome.)

It turns out, for data analysis, technique takes a backseat to domain knowledge. Analyzing English requires understanding it. Digging deeper into phonetics, I hit another snag: triphthong identification is incredibly ambiguous. There’s no consensus on whether three vowel symbols together are a triphthong or a monophthong + diphthong. That familiar feeling… Classic English! No rigid rules.

Consider fire /ˈfaɪər/. Some claim aɪə is one syllable; others say it’s aɪ + ə (two syllables). Criteria vary wildly. Some use hyphenation (you can write “fi-” and “re,” but not “fire,” so it’s a triphthong). Others use singing: if sung as one note, it’s a triphthong. In Simple Plan - Fire In My heart, at 0:57, faɪ and ər are sung as separate notes—should it be a diphthong + monophthong?

Oh well, that’s English. Given words like oasis /oʊˈeɪsɪs/ (four vowels!), with oʊ and eɪ clearly separated by the stress mark (obviously two diphthongs), I disregarded triphthongs, treating them as two syllables. The only remaining “triphthongs” were diphthongs with a long vowel marker.

Besides syllable count and stress position, I wanted the stressed vowel itself, potentially for further analysis.

This was trickier. I discussed it with AI, revealing significant model differences. Gemini 1.5 Flash went in circles. GPT-4o provided the correct code in three conversational rounds (about 10 minutes). Claude 3.5 Sonnet got it right immediately. For coding, a good model is worth the cost, though basic code literacy is essential to understand the AI’s code, its functionality, and potential issues.

Here’s the logic, again with analytical /ænəˈlɪtəkəl/:

- Locate the stress mark

ˈand consider the subsequent part:lɪtəkəl. - Iterate, removing non-vowels until the first vowel:

ɪtəkəl. - The first character is now a vowel. Check the first 3 characters (

ɪtə) against the triphthong set. Nope. - Check the first 2 (

ɪt) against the diphthong set. Nope. - Check the first character (

ɪ) against the monophthong set. Found it! That’s the stressed vowel.

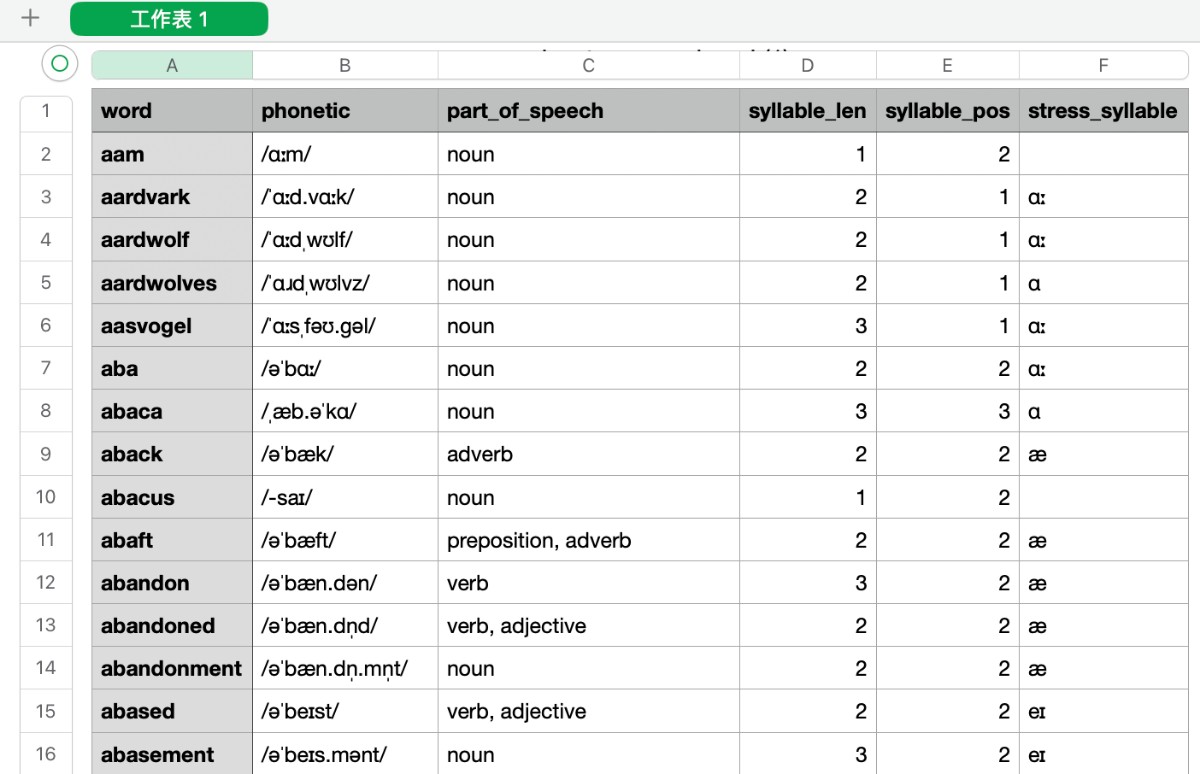

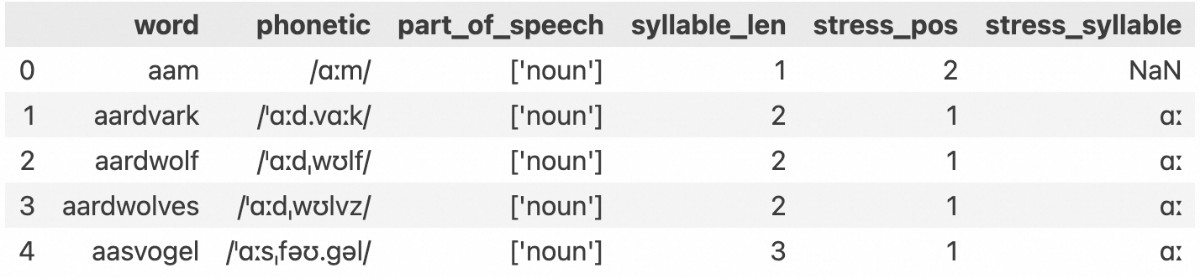

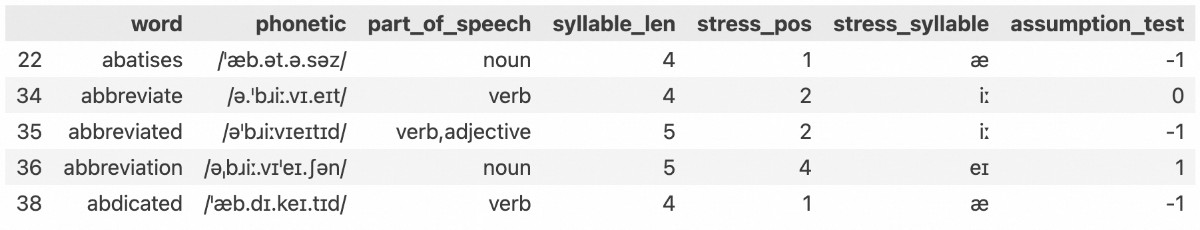

The data table after phonetic analysis. All necessary data was now collected.

Visualization

Now for the highlight—not just for deriving useful conclusions, but also because AI shines here. AI is excellent at writing Python visualization code. These tasks are less about reasoning and more about knowing the visualization library’s syntax. Even Gemini 1.5 Flash, a non-flagship model I use daily, performs well. I haven’t formally learned Seaborn and Matplotlib, but with AI, generating plots is straightforward.

Of course, “straightforward” doesn’t mean “ask and receive.” Giving AI a vague request without context leads to failure. I crafted a Python visualization prompt, detailing the task and the data table’s structure, enabling the AI to perform with full power and stability.

<Task>

You are a Python data visualizer. You excels at coding with data visualization libraries like Seaborn and Matplotlib. I will tell you about the structure of a Pandas dataframe and the visualization I want. First, you dive deeply into the dataframe and understand what it is all about. Then write Python code to visualize it. Just code, no explanation. Next, you check if the code meets my need. Finally, correct the code if necessary.

<Dataframe>

The dataframe(variable name is df) is {a list of common English words with their phonetic information and part-of-speech}.

Now here are the columns of the dataframe, exactly in the following order:

**word**

- datatype: str

- example: complimentary

- description: the English words

**phonetic**

- datatype: str

- example: /ˌkɒmplɪ̈ˈment(ə)ɹɪ/

- description: the phonetic transcription of the words

**part_of_speech**

- datatype: str(list like)

- example: ['adjective']

- description: how are these words used in sentences

**syllable_len**

- datatype: int

- example: 5

- description: how many syllables are there in these words

**stress_pos**

- datatype: int

- example: 3

- description: on which syllable the stress falls on, if there are more than one stress, this is the position of the first stress

**stress_syllable**

- datatype: str

- example: e

- description: the vowel of the stressed syllable

<Request>

I want to know the distribution of stress position, grouped by syllable numbers.

To use the prompt, just tweak the <Request> section.

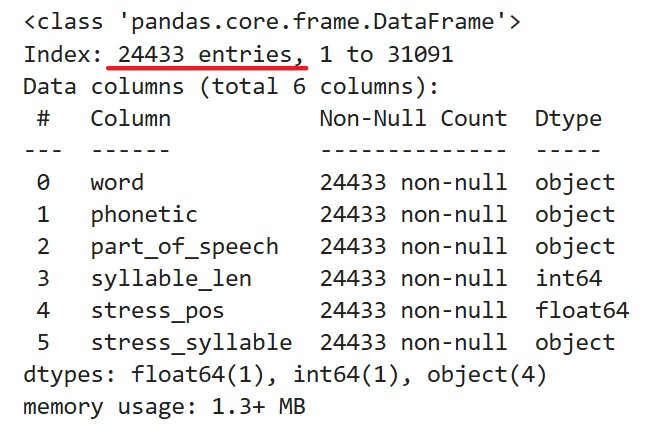

Some words in the data lack stress marks because they’re short, and their phonetic transcriptions don’t show stress. Let’s filter those out, along with one-syllable words – analyzing stress in those is pointless.

This leaves 24,433 words with complete data.

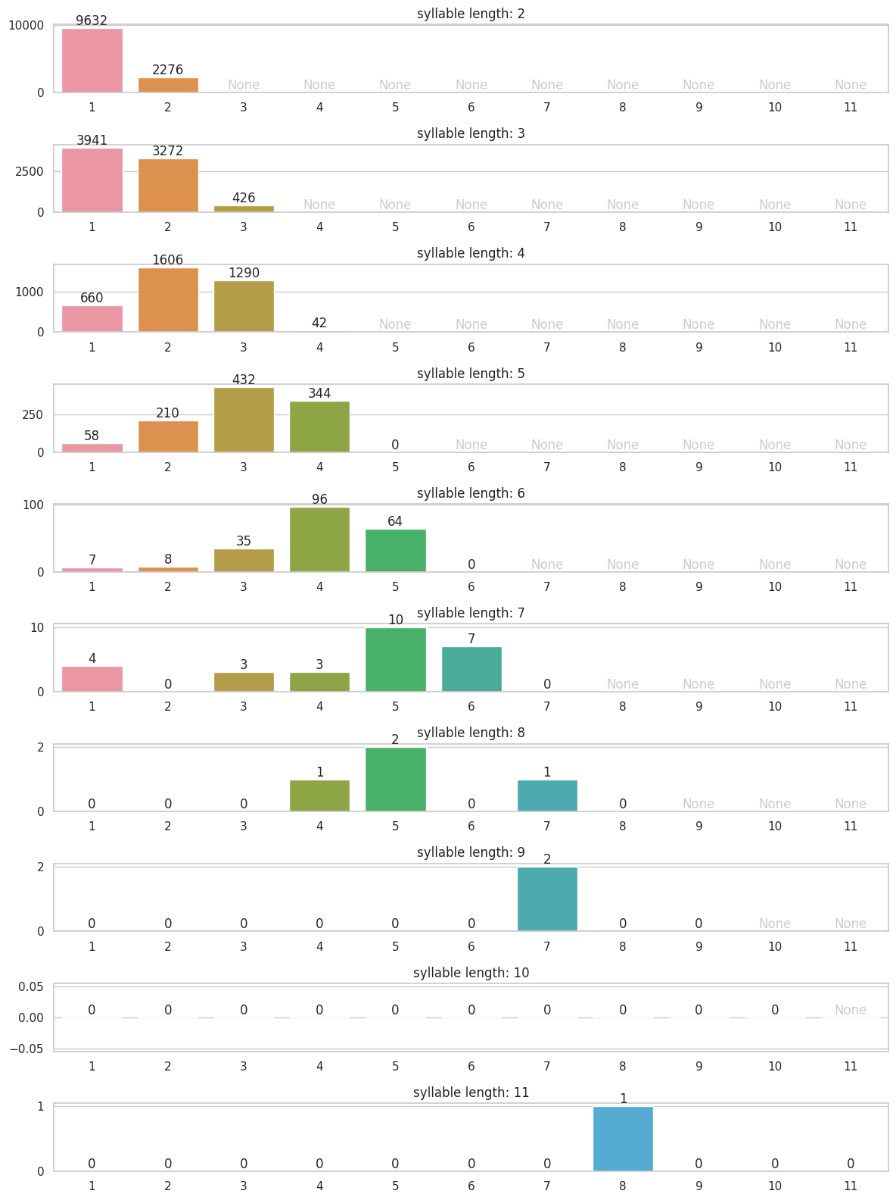

Syllable Count Analysis

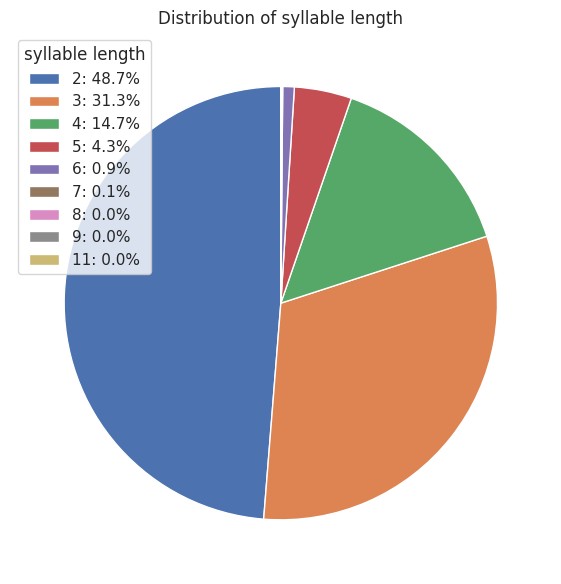

Let’s break down the syllable counts of these 24,433 words.

Unsurprisingly, fewer syllables mean more words. Languages tend to use up short, easy words first.

Two-syllable words make up 48.7%, three-syllable words 31.3%.

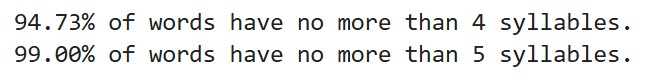

Words with four or fewer syllables make up 94.73%; five or fewer, 99%.

The longest word has 11 syllables.

“Antidisestablishmentarianism”? Really? Opposition to opposition – double negative much? No wonder it’s so long. Could I just add “non-” to create “nonantidisestablishmentarianism”?

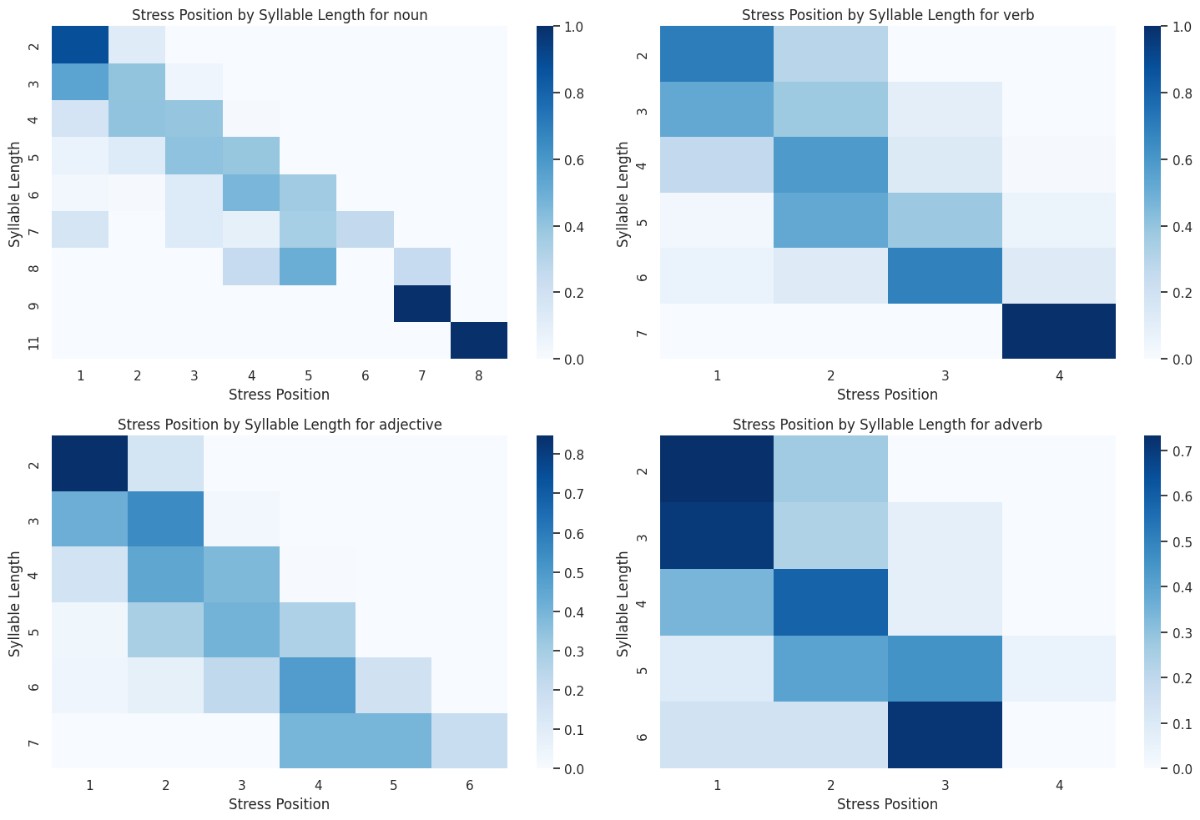

Syllable Count vs. Stress Position

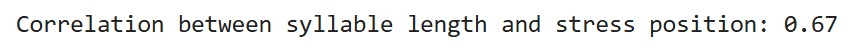

Statistically, the correlation coefficient is 0.67 – a pretty decent correlation.

This coefficient ranges from -1 to 1. Near 0 means almost no relationship; near 1, positive correlation (one up, other up); near -1, negative correlation (one up, other down).

This is just a first step, showing they’re not unrelated. It doesn’t explain why.

A bubble chart helps. Syllable count is on the y-axis, stress position on the x-axis, and bubble size/color shows the word count. The dots roughly follow a diagonal – more syllables, later stress.

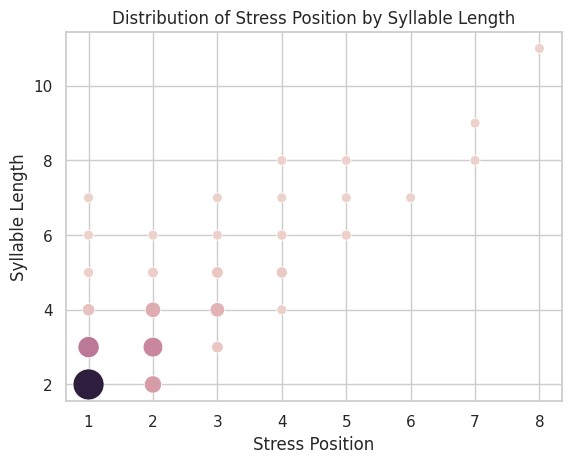

Bubble charts (or heatmaps) show three dimensions but compare absolute word counts. I care more about stress position distribution within each syllable count.

Here’s a stacked bar chart: syllable count on the y-axis, stress position on the x-axis. Now it’s clear: stress shifts right like a wave, clustering around the third-to-last syllable.

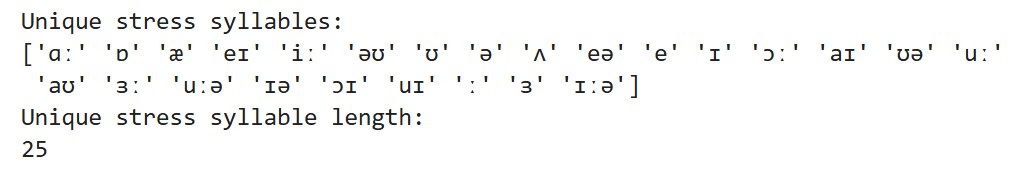

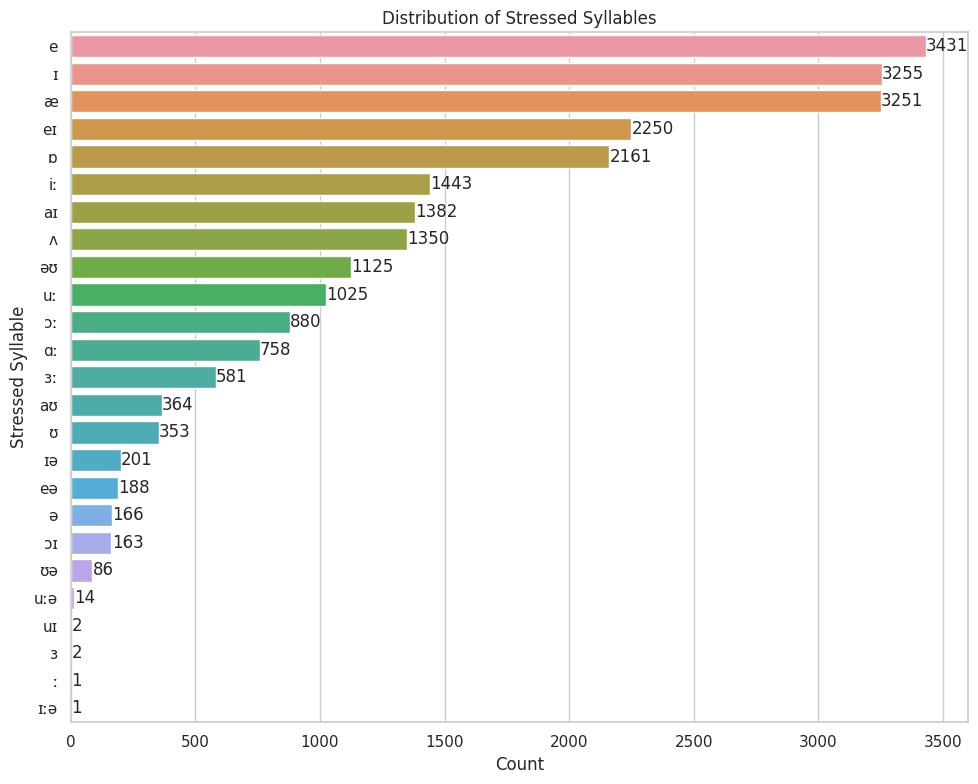

Stressed Syllable Analysis

These are all the vowels in stressed syllables. A couple shouldn’t be here, but it’s a dictionary error, and too few to matter.

By frequency, louder vowels like æ and e are more likely stressed; weaker ones like ə and ʊ are less common.

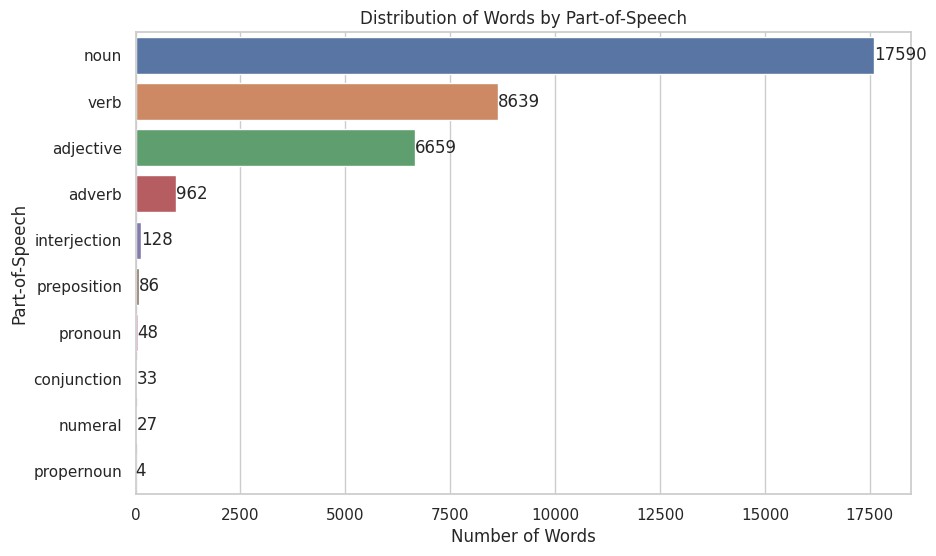

Part of Speech Analysis

Is there a link between part of speech and stress?

All part of speech: ['adjective', 'adverb', 'conjunction', 'interjection', 'noun', 'numeral', 'preposition', 'pronoun', 'propernoun', 'verb']

Here’s a breakdown of all parts of speech. I’m not sure what “propernoun” is – it’s not in my dictionary either. It turns out there are only two, and they don’t seem to fit, so I suspect a data glitch with the dictionary API. I’ll skip it for now.

I ranked the parts of speech by frequency. The big ones are nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. Nouns account for roughly half the total.

This gets you thinking about how language evolved. First, you need to describe the world and create concepts – that’s where nouns come in. Then, to describe how people and things interact, you need verbs. After that, adjectives and adverbs develop to modify nouns and verbs. So, my guess is the number of words should follow that order.

But wait – shouldn’t the ratio of nouns to adjectives, and verbs to adverbs, be roughly the same? No need to calculate. The bar chart makes it obvious: nouns are more than double the adjectives, and verbs outnumber adverbs almost nine to one. They’re way out of proportion.

['abracadabra', 'absolutely', 'action', 'adieu', 'adios', 'affirmative', 'afternoon', 'ahem', 'alack', 'aloha', 'alright', 'amen', 'amidships', 'arrivederci', 'attaboy', 'attention', 'away', 'banzai', 'bastard', 'beauty', 'begone', 'begorra', 'behold', 'blazes', 'bollocks', 'bonjour', 'bother', 'botheration', 'brother', 'bully', 'bullseye', 'bullshit', 'caramba', 'checkmate', 'cheeses', 'condolences', 'congrats', 'congratulations', 'content', 'cooee', 'curses', 'dammit', 'ecce', 'egad', 'enchanted', 'encore', 'enough', 'eureka', 'exactly', 'farewell', 'fiddlesticks', 'flummery', 'gadzooks', 'gesundheit', 'goddamn', 'goodbye', 'gorblimey', 'gracias', 'gracious', 'greetings', 'hallelujah', 'hardly', 'havoc', 'heavens', 'heyday', 'hola', 'holla', 'honestly', 'hooray', 'hosanna', 'howdy', 'hullo', 'hurrah', 'huzzah', 'yeah', 'indeed', 'knickers', 'later', 'mercy', 'morepork', 'morning', 'namaste', 'negative', 'nonsense', 'oyez', 'okay', 'ole', 'pardon', 'peccavi', 'period', 'pity', 'pleasure', 'presto', 'prithee', 'prosit', 'quiet', 'rather', 'really', 'respect', 'result', 'roger', 'rumble', 'sayonara', 'scramble', 'selah', 'shabash', 'shazam', 'silence', 'sorry', 'standard', 'sugar', 'tally', 'tara', 'tarnation', 'tidy', 'timber', 'uncle', 'understood', 'viva', 'vivat', 'voetsek', 'warning', 'welcome', 'whammo', 'whatever', 'wilco', 'wirra', 'zowie']

I listed all the interjections out of curiosity. I don’t usually give this part of speech much thought, so I took a closer look. Surprisingly, “afternoon” is also classified as one! Which makes sense, since it’s a greeting.

['abaft', 'abeam', 'aboard', 'about', 'above', 'abreast', 'abroad', 'absent', 'across', 'afore', 'after', 'again', 'against', 'agin', 'along', 'alongside', 'aloof', 'alow', 'amid', 'amidst', 'among', 'amongst', 'anent', 'anti', 'around', 'asprawl', 'astraddle', 'astride', 'athwart', 'barring', 'bating', 'because', 'before', 'behind', 'beyond', 'below', 'beneath', 'beside', 'besides', 'between', 'betwixt', 'circa', 'concerning', 'considering', 'contra', 'despite', 'during', 'except', 'excepting', 'failing', 'following', 'forby', 'froward', 'given', 'including', 'inside', 'into', 'minus', 'modulo', 'nearer', 'nearest', 'onto', 'opposite', 'outwith', 'pending', 'regarding', 'regardless', 'respecting', 'rising', 'running', 'saving', 'thorough', 'throughout', 'touching', 'toward', 'towards', 'under', 'underneath', 'unlike', 'until', 'upon', 'upside', 'versus', 'wanting', 'within', 'without']

When listing out prepositions, I noticed some recurring prefixes:

- a- indicating location or spatial relationship: aboard, across, amid, around

- be- (basically be): before, behind, below, beside

Next, I created heatmaps for each part of speech. The y-axis shows syllable count, the x-axis shows stress position, and color intensity represents the proportion of words for each syllable count. I only included parts of speech with over 1% of the total words, as others had too few to be significant.

Stress tends to shift towards the end as syllables increase. The difference between parts of speech isn’t huge, but it’s there. For longer words (5+ syllables), adjectives often have stress on the antepenultimate (third-to-last) syllable, nouns tend to have stress further back, and verbs/adverbs have stress further forward.

Rules of Stress Position

It was time to test my hypothesis.

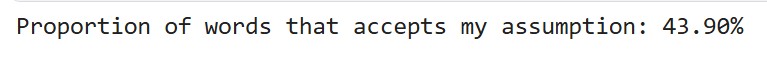

I analyzed 4- and 5-syllable words, adding a column showing the difference between the actual and hypothesized (third-to-last) stress positions. A ‘0’ means a match, ‘1’ means one syllable later, ‘-1’ one syllable earlier, etc.

The hypothesis held for 43.9% of the words.

This bar chart shows the stress deviation. Most words follow the rule, with some shifted by one syllable. Very few are further off. It kind of looks like a normal distribution (but I’m no stats expert).

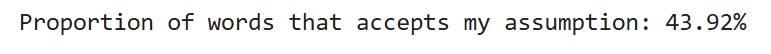

Then I wondered: could this be generalized? Does it apply to words with 5+ syllables? I broadened the filter to include all words with over 3 syllables:

43.92% fit. Almost no change.

The deviation pattern remained. Most words are stressed on the antepenultimate syllable, many on the penultimate. Combined, they account for 78.84%. It’s not a perfect fit, but the general trend is confirmed.

Conclusion

Here’s a recap of the findings regarding phonetics and stress:

- Fewer syllables mean more words.

- Words with 5+ syllables are rare in everyday use.

- The longest word found has 11 syllables.

- Stress generally shifts towards the end in longer words.

- Louder vowels are more likely to be stressed.

- Part of speech has a minor effect on stress.

- Most long words are stressed on the antepenultimate or penultimate syllable (78.84%).

Afterword

Five minutes of analysis, two hours of data prep – seriously.

Visualization took only half a day. Data preparation, especially fetching phonetic transcriptions via the dictionary API, took the longest. The script ran on and off for over two weeks; I even finished writing this before the dictionary lookup was done, using placeholders for the data.

I’m happy the results confirmed my hypothesis. After this, I doubt I’ll ever forget English stress rules – it’s my own research, after all.

This project refreshed my Pandas skills, taught me batched requests and incremental saving, showed me how to integrate AI into analysis, helped me write effective Python data visualization prompts, and deepened my understanding of English phonetics. A huge win, and totally worth it!

Thanks to:

- Word data source: This 300k+ word list was the base of my analysis.

- Free Dictionary API: This provided an inexpensive way to get phonetic transcriptions.

- Gemini 1.5 Flash: Helped with about half the data prep and all the visualizations.

- GPT-4o: Helped accurately ID vowels in stressed syllables.

The full analysis and code are open-sourced on Kaggle. Check it out if you’re interested:

https://www.kaggle.com/code/victorcheng42/stress-distribution-of-english-words

The dataset with phonetic transcriptions, syllable counts, and stress positions is also public. It might be useful for other analyses:

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/victorcheng42/english-words-with-stress-position-analyzed