This question just popped into my head. I bet my daughter will ask it when she’s a bit older. Pause for a moment and think, how would you answer it?

Think carefully. A serious answer, please. No wise cracks.

This detailed explanation is probably best saved for when my daughter is in middle school. If she asked me right now, I’d probably just say, “Because water cools things down, so the fire can’t keep burning.”

But that’s fine. I’m the one who’s curious, so let’s dive deeper.

What is Fire?

To understand how to extinguish a fire, you first have to understand fire itself.

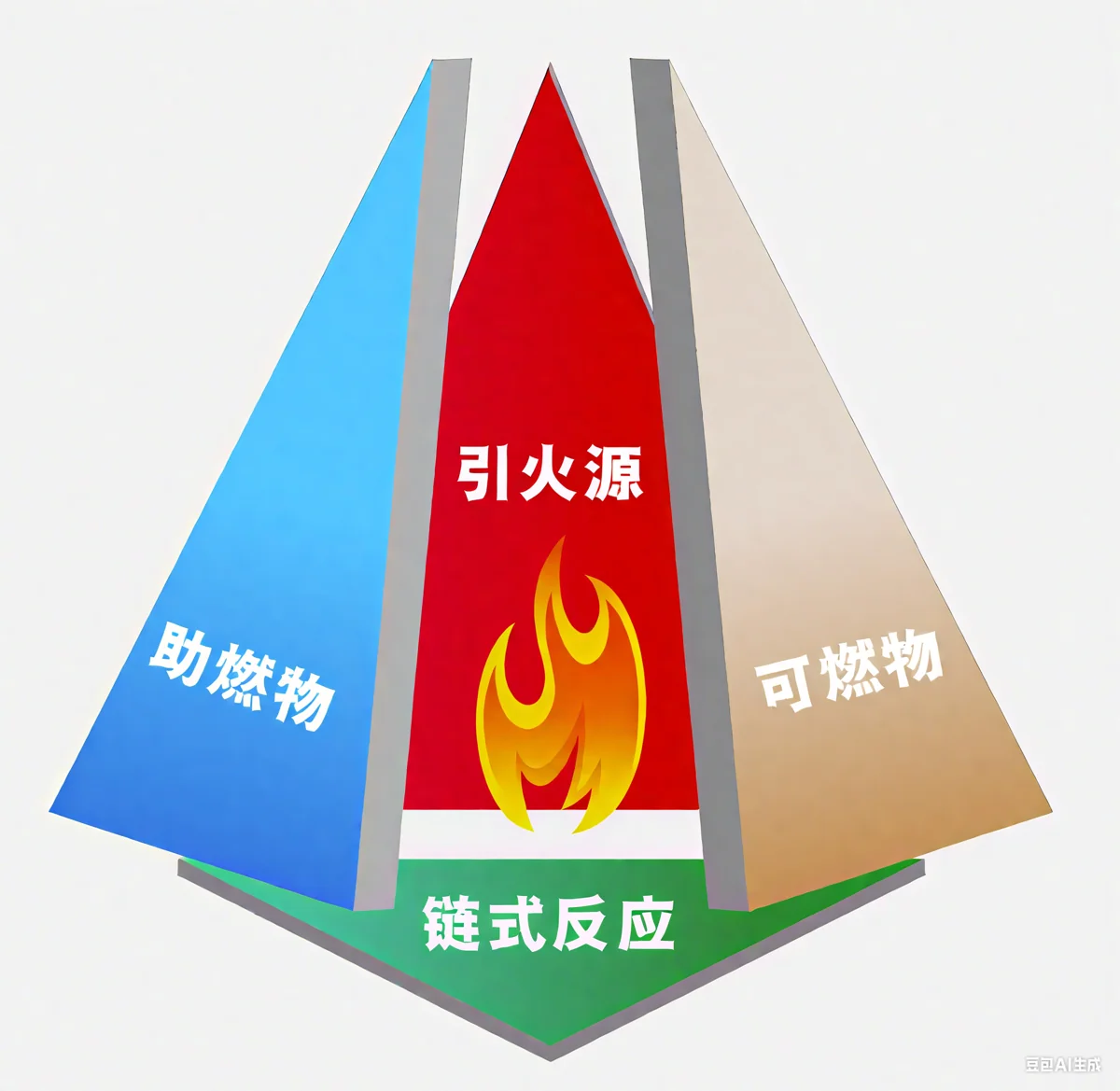

High school chemistry taught us that combustion requires three elements, forming the “fire triangle”:

- Fuel: Something that can burn, like wood or gasoline. These are essentially reducing agents.

- Oxidizer: Something that helps things burn, usually oxygen from the air. These are oxidizing agents.

- Heat: Something that provides the initial energy, like the heat from a match.

All three must be present.

By the way, oxygen isn’t the only oxidizer. Hydrogen can burn in chlorine, and many substances burn violently in fluorine. It’s just that on Earth, oxygen is the most common one.

This is a scientific approach: for water to put out a fire, it must remove at least one of these three elements. Which one? Let’s hold that thought and dig deeper.

Now, let’s step into the microscopic world of chemistry and see how these three elements ignite.

Here’s a little-known fact: liquids don’t actually burn. The vast majority of combustion we see happens in the gas phase.

At a microscopic level, combustion is a rapid, violent oxidation-reduction reaction where fuel molecules and oxidizer molecules collide at high speed, turning into other molecules and releasing light and heat. For efficient collisions, the best state is a gas, where everything is thoroughly mixed.

Let’s do a thought experiment with a cup of gasoline. We’ll put it in a special device that’s both a freezer and an oven, and slowly heat it from near absolute zero (the coldest temperature in the universe) without an open flame:

- At about -40°C, gasoline molecules gain enough energy to evaporate from the liquid surface into a gas. This gasoline vapor spreads into the air, with higher concentrations near the liquid surface. A quick spark will ignite this thin layer of vapor in a “poof,” and then the flame will extinguish. This temperature, -40°C, is the flash point of gasoline; from this temperature on, it can be ignited.

- Continue heating. At about 280°C, something amazing happens: even without an external heat source or a spark, the gasoline suddenly bursts into flame and burns until it’s gone. This is the autoignition temperature. At this temperature, the collisions between gasoline vapor and oxygen molecules are so violent that for every molecule that burns, the heat it releases vaporizes another one from the cup.

See? The secret to a sustained flame is the evaporation rate. The hotter it gets, the faster it evaporates. At the autoignition temperature, the rate of vapor production meets or exceeds the rate of consumption by burning. Once this fuel supply line is established, combustion becomes a self-sustaining positive feedback loop.

The Peculiarity of Solid Combustion

The combustion of solids is more complex than that of liquids. Let’s use burning wood for another thought experiment.

The burning of wood occurs in two stages:

Stage 1: Flaming Combustion.

When wood is ignited, the complex organic macromolecules inside it break down in a process called pyrolysis. Pyrolysis produces two things: flammable gases (like methane and carbon monoxide) and solid charcoal (which is almost pure carbon).

This process is similar to liquid combustion, but “evaporation” is replaced by “pyrolysis.” Evaporation is a physical change—the molecules themselves don’t change. Pyrolysis is a chemical change—large molecules break down into smaller gas molecules. These flammable gases mix with the air and burn, creating a beautiful flame around the wood. Since hot gas rises, flames always appear at the top.

Stage 2: Smoldering.

When most of the gas has burned off, the flames disappear, leaving glowing red embers. Flaming combustion is over, and the flameless smoldering phase begins.

This process is more like a close-quarters battle. Oxygen molecules, the attackers, charge directly at the surface of the charcoal to react with the carbon atoms. The product, carbon dioxide, is a gas and flies away immediately. Fresh carbon atoms from below move up to the front line. This cycle repeats until the charcoal is consumed. The remaining ash consists of non-carbon impurities.

The pure surface combustion of charcoal has a huge advantage: it’s stable and controllable.

Its rate of heat release mainly depends on two variables: the fuel’s surface area and the oxidizer’s supply. The surface area is nearly constant, so the only variable is the oxygen supply. Therefore, its heat output can be precisely controlled, making it an ideal fuel, not just for its high heat value.

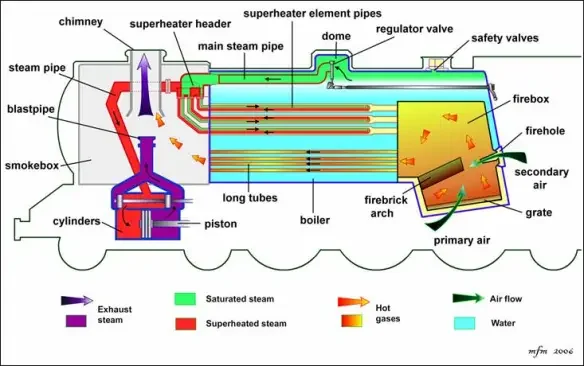

This property has special applications. Take steam locomotives, for instance, which burn coal (similar to charcoal). The fireman can control the fire’s intensity by adjusting the damper, which regulates the airflow into the firebox. This, in turn, controls steam production and the locomotive’s power.

Purple arrows show exhaust gas being expelled, which draws hot yellow-orange gas from the firebox. The firebox then sucks in fresh air, shown by the green arrows.

Even more clever is the blastpipe in the chimney. It ejects exhaust steam from the pistons at high speed, creating a vacuum that fiercely sucks fresh air into the firebox. This is based on the Bernoulli principle: the faster a fluid flows, the lower its pressure. The more the blastpipe blasts, the stronger the draft, the more oxygen enters the firebox, the hotter the fire burns, and the more steam is produced. It’s a brilliant positive feedback loop.

So, what if both the fuel and the oxidizer are solids? Does that kind of combustion exist?

Yes. The classic example is the thermite reaction. Mix aluminum powder (the fuel) with iron oxide powder (the oxidizer) and ignite it. The aluminum will snatch the oxygen atoms directly from the iron oxide. This solid-solid reaction releases temperatures up to 2500°C, hot enough to melt the resulting iron. The liquid iron allows the powders to flow, promoting continuous contact and sustaining the reaction.

To take it a step further, what happens if you strongly heat a solid fuel without an oxidizer?

It will only pyrolyze, not burn. This is a crucial part of modern chemical engineering. For example, heating coal without air (dry distillation) yields three important industrial materials: coke (for steelmaking), coal tar (a chemical feedstock), and coal gas (a fuel).

Now back to a fundamental question: Why does charcoal undergo pure surface combustion, while liquid fuels do not? This stems from differences at the molecular level.

Gas molecules are like rubber ducks in a pool, floating around randomly and bumping into each other.

Liquid molecules are like a pile of Buckyballs, held together by weak forces but able to slide past each other. This weak attraction is easily overcome by heat, allowing them to evaporate and escape.

Solid atoms (like carbon), however, are like a structure built with mortise and tenon joints. Each atom is locked in place by strong chemical bonds. The heat of combustion is not nearly enough to break this structure, so the atoms cannot escape as a gas and can only react on the surface. For instance, carbon’s autoignition temperature is a few hundred degrees, but its sublimation point (the temperature at which it turns to gas) is over 3600°C. It would have burned away long before it could vaporize.

The Essence of Combustion

By now, you might suspect the “fire triangle” model is a bit too simple. The conditions for brief combustion and sustained combustion are different.

- Brief combustion: Requires fuel, an oxidizer, a temperature high enough for evaporation/pyrolysis, and an external ignition source.

- Sustained combustion: Requires fuel, an oxidizer, and a temperature at the autoignition point.

The fire triangle model can’t explain why a flame is self-sustaining. So, scientists proposed the “fire tetrahedron,” adding a fourth element: an uninhibited chain reaction.

Once combustion starts, oxidizer and fuel molecules collide violently, creating new molecules and releasing heat. But that’s not the most powerful part of the chain reaction.

Besides collisions between whole molecules, many molecular “fragments” called free radicals are also involved. These are molecules that have been damaged in previous violent collisions. Some have lost an electron; others have an extra one. Free radicals are like hungry wolves, frantically attacking other molecules to become stable. This intensifies the collisions, generating more heat and more free radicals.

This process self-replicates and self-amplifies like a snowball rolling downhill. This is what makes fire so terrifying and magnificent. The power humans gained from mastering fire wasn’t just the heat of a torch against a wild beast. It was the leverage—a single spark could burn a prairie, providing cooked food and clearing land for farming. This power overwhelmed the physical strength of any other species.

Another chain reaction we’re familiar with is the one in an atomic bomb.

Speaking of which, what is an explosion? Is it brief or sustained combustion?

A (chemical) explosion is usually classified as brief combustion. When enough flammable gas has accumulated in the air at its flash point, a local ignition source reaching the autoignition temperature can trigger an extremely fast chain reaction. During the accumulation phase, the ambient temperature must remain below the autoignition temperature; otherwise, it would burn up before it could accumulate.

The Answer Revealed

Let’s summarize the microscopic combustion process:

- Gaseous fuel: The most direct; burns when mixed with an oxidizer.

- Liquid fuel: Must first evaporate into a gas.

- Solid fuel: Mostly needs to first pyrolyze into a gas (flaming combustion), with the remainder undergoing surface combustion (smoldering).

As you can see, with few exceptions, most combustion follows the same path, shifting the battlefield to the gas phase.

Now, we can finally answer the original question. How exactly does water put out a fire? It attacks the “fire tetrahedron” on two fronts:

- Attacking “Heat” (Cooling): This is water’s primary role. Water has an extremely high heat of vaporization; one gram of water turning into steam absorbs about 2260 joules of heat. To put that in perspective, that’s enough energy to lift a 100 kg (220 lb) person more than 2 meters (7 feet) off the ground. When water hits a fire, it absorbs a massive amount of heat, preventing the fuel from vaporizing and thus breaking the chain reaction.

- Attacking the “Oxidizer” (Suffocation): This is a secondary factor. The huge volume of water vapor produced expands by more than a thousand times, displacing oxygen and stopping the combustion.

Of course, not all fires can be put out with water:

- Electrical fires: Water conducts electricity and can cause electric shock or short circuits.

- Oil fires: Oil is lighter than water and will float on top, spreading the fire as the water flows.

- Reactive metal fires: Metals like potassium, sodium, and magnesium react with water to produce flammable hydrogen gas, essentially adding fuel to the fire.

Ultimately, the main reason water extinguishes fire is its powerful cooling ability. The same as the simple answer at the beginning.

But the journey of exploration is what’s interesting. An answer given without thought and one reached after a deep dive carry completely different weights.

If I’d known all this back in middle school, maybe I wouldn’t have failed chemistry.