Let’s Talk Travel Plans

With a young child, we haven’t traveled far in years. Now that she’s older, international travel is on the table, though likely not until next year.

Our annual leave is limited, and a kid can’t handle a ten-plus hour flight, so our options are pretty narrow:

- East: Japan and South Korea are culturally similar to us, not ideal for an “exotic” experience, though Tokyo Disneyland is a big draw.

- South: A few relatively safe Southeast Asian countries and plenty of resort islands. Very suitable, worth considering.

- West: The “-stan” countries. Exotic, for sure, but unfamiliar territory, and my wife isn’t interested.

- North: Our neighbors, Mongolia and Russia. Not too keen on Mongolia, and Russia’s main attractions are in its European part, which is too far.

While lamenting the slim pickings, I realized I’d overlooked one direction: the other side of the Himalayas, the Indian subcontinent.

India is rarely on the radar for Chinese travelers, but the region is more than just India. I distinctly remember seeing three countries on the southern Himalayan slopes on maps as a kid: Nepal, Bhutan, and Sikkim. I even nicknamed them the “Himalayan Trio.”

Wait a minute… what happened to Sikkim?

Sikkim’s History: Swept Away by External Forces

A quick look at any map app—Baidu or Google—shows Sikkim clearly labeled as a state of India. The sovereign nation that once served as a buffer between China and India has silently vanished.

Some digging unearthed a buried chapter of history.

On April 14, 1975, the Kingdom of Sikkim held a referendum on whether to abolish the monarchy. A staggering 97.5% voted to depose the king and merge with India. A month later, India’s Parliament amended its constitution, and Sikkim officially became India’s 22nd state. Just like that, a kingdom that had existed for over 300 years was erased from the map after a seemingly “democratic” vote.

The process appeared impeccable: the Sikkimese people “voluntarily” renounced sovereignty, and India “honored their wishes.” But under international law, can a “merger” between two nations be considered legitimate under such circumstances?

This hits on a fundamental conflict in international law: the right to “self-determination” versus the “prohibition of the threat or use of force.” A people has the right to freely choose its destiny. But what if that choice is made at the barrel of a foreign army’s gun? Such “consent” is invalid. Sikkim’s referendum took place while the Indian army controlled the capital and had the king under house arrest. It was less an expression of popular will and more a political strong-arming.

After their country’s fall, Sikkim’s last king, Palden Thondup Namgyal, and his American queen, Hope Cooke, went into exile in the U.S. They didn’t go quietly. They spent their lives campaigning for restoration, lobbying the U.S. Congress, and giving interviews to expose the truth of India’s annexation. But against the backdrop of the Cold War, their tragic efforts earned sympathy but no tangible support. The king died of cancer in 1982, and with him, the dream of a sovereign Sikkim was extinguished.

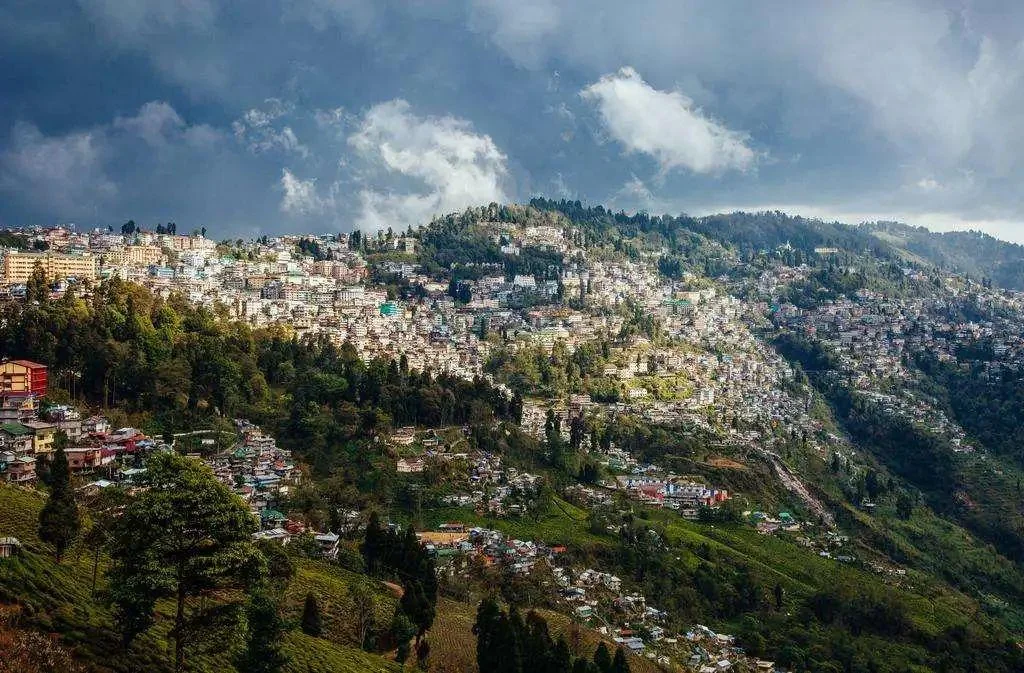

To grasp this tragedy, you have to look further back. Sikkim, once known as Drenjong, was a tributary state of China’s Qing Dynasty with deep cultural ties to Tibet. In the 19th century, as British colonialism swept South Asia, Sikkim’s protectorate status shifted to the British Empire. To exploit the region, the British forcibly leased Darjeeling and imported vast numbers of Nepali laborers, sowing the seeds for Sikkim’s eventual demise.

Darjeeling

In 1947, an independent India inherited the British Empire’s sphere of influence and ambitions. By 1950, a treaty made Sikkim an Indian “protectorate,” giving India control over its defense, foreign affairs, and economy.

For the next two decades, India cultivated political parties of Nepali immigrants, exacerbating tensions with the native Tibetan Buddhist ruling class. As the Cold War peaked in the 1970s, India saw its opening.

The U.S. was bogged down in Vietnam and had no bandwidth for other conflicts. The Soviet Union, seeking to counter China, had formed a quasi-alliance with India, giving it a free hand in the region. And China was in the throes of the late Cultural Revolution; it issued the strongest condemnations but lacked the capacity for any meaningful military intervention.

Another critical factor: Sikkim was not a member of the UN. Since coming under British influence, it had never truly had foreign policy autonomy, and neither of its powerful patrons had any interest in giving it a seat at the table.

With the tacit approval of global powers and no one to intervene, India moved its troops into Sikkim in 1973, took over the government, disbanded the king’s guard, and orchestrated the 1975 “referendum.” A sovereign nation disappeared from the map, largely ignored by the international community. China only formally recognized Indian sovereignty over Sikkim in 2003 as part of normalizing relations, updating its official maps in 2005.

The Prime Movers: Geography and Demographics

Beyond the geopolitics, Sikkim’s fate was sealed by two cold, unforgiving factors: demographics and geography.

A nation’s foundation is its people—its “hardware.” The national narrative is the “operating system” (OS) running on it. A cheap way to weaken a nation is to attack its OS, making citizens question their identity and hindering the state’s ability to mobilize resources. Great powers do this constantly.

But if a nation’s population is below a critical mass, its hardware is inherently vulnerable. An external power doesn’t need to corrupt the OS; it can simply replace the hardware by engineering a population shift.

This was Sikkim’s tragedy. In 1975, its population was under 500,000. For context, a large residential complex in a Chinese city can house 10,000 people. Fifty such complexes—a mere sub-district in Guangzhou—was the entirety of Sikkim. It stood no chance against India’s demographic might. The influx of Nepali immigrants, which began under the British, fundamentally altered Sikkim’s ethnic and religious makeup. The rule of the monarchy, rooted in the native ethnic group and Tibetan Buddhism, was already on shaky ground. Once the immigrants became the majority, India only had to fan the flames and, under the guise of “democracy,” have this new “hardware”—now over 90% replaced—vote to delete the original “OS.”

Geography, meanwhile, creates the notion of a “sphere of influence,” motivating regional powers to expand. The tendency for a regional power to view smaller neighbors within its geographical sphere as its own backyard is a timeless geopolitical rule. They don’t have to be annexed, but they must be allies or, at a minimum, buffer zones.

The Indian subcontinent, enclosed by the sea on three sides and the world’s highest mountains to the north, is a self-contained theater. This is India’s home turf. It’s the same logic as the 19th-century U.S. Monroe Doctrine, which used the Atlantic and Pacific oceans as barriers to declare the Americas its domain. The underlying principle of the war in Ukraine is no different: a great power will not tolerate a hostile “OS” being installed in its core sphere of influence.

The situation in South Tibet (which India calls Arunachal Pradesh) is another product of this dynamic. This territory is not a case of annexation but a dispute between two major powers. Yet the underlying forces shaping the reality on the ground are identical.

Picture the region as a giant, south-sloping roof. India, situated below the eaves, can easily advance up the natural river valleys. China, on the other side of the Himalayan ridge, must first brave high-altitude, low-oxygen conditions, cross the crest, and then descend what are essentially sheer cliffs on the northern slope. This geographical asymmetry allows India to easily project its population and administration onto the southern slope, establishing de facto control. Although China decisively won the 1962 war and briefly controlled the area to assert its claim, maintaining long-term control was prohibitively costly. Withdrawing troops and shifting to a diplomatic standoff was, therefore, a pragmatic, if not ideal, outcome.

Ultimately, under the immense pressures of demography and geography, the tiny nation of Sikkim was simply erased. Its independence had been nominal long before the annexation. What I saw on the map as a child was merely its ghost. History can be that cold.

Wary Neighbors: Bhutan and Nepal

Sikkim’s fate was a chilling lesson for its neighbors, Bhutan and Nepal. The fear of being next keeps them perpetually wary of India’s ambitions.

It’s not that India lacks ambition, but that the cost and risk of repeating that playbook have become too high. To survive, Bhutan and Nepal have worked hard to secure their “hardware” and bolster their “software.”

First, the demographic “hardware.”

In 1975, Bhutan’s population was several times Sikkim’s, but still in the same order of magnitude. Nepal’s, however, was in the tens of millions. A demographic takeover was plausible in Bhutan, but having learned from Sikkim, it took active measures to protect its population. Nepal, on the other hand, is a veritable “ethnic mosaic” with over 140 recognized groups, none comprising more than 17% of the population. This hyper-diversity makes it difficult to subvert the state by backing any single group. Still, deep economic and religious ties bind Nepal to India.

Over 80% of Nepal’s population is Hindu

More crucial is the “software” of national identity.

Nepal’s pride in never having been fully colonized provides a historical foundation for its independence. Ironically, India’s relentless political meddling has become the most effective glue uniting its diverse ethnic groups.

Bhutan, with a similar profile to Sikkim, is more vulnerable. But it has astutely cultivated a unique national narrative around “Gross National Happiness” while fiercely guarding its demographic integrity. Since the 1950s, the government has pursued policies to assimilate or expel Nepali immigrants to protect its majority culture. This proactive “hardware maintenance” preserved its ethnic and cultural independence, preventing it from being hollowed out from within. Nevertheless, trapped by geography and economic dependence, it cannot escape India’s pervasive influence. India is a formidable presence they cannot simply wish away.

Bhutan’s culture is very similar to Tibet’s

Watching these two small nations deploy every strategy available, one can only imagine the immense effort a large country must expend to maintain its own national narrative.

Ironically, India struggles to tell its own national story, which weakens its ability to undermine others’. The official narrative, “Unity in Diversity,” feels abstract. For most Indians, identities like “Hindu,” “Muslim,” “Tamil,” or “Punjabi” are far more tangible in daily life than the modern concept of “Indian.” India can’t export a story more compelling than “the glory of the Gurkhas” or “the happiness of the Dragon Kingdom” because its own “OS” is a patchwork system built for compatibility, not conversion.

Today’s global environment has also changed. Globalization interconnects all nations, and social media can amplify any conflict instantly, making victory in the court of public opinion as important as victory on the battlefield. Sikkim’s annexation was a regional affair; a similar act today would be a global scandal. While geography and demographics in South Asia favor India, the efforts of Nepal and Bhutan allow them to maintain political independence and avoid internal collapse. For everything else, they are deeply intertwined with India. The forces that preserve their fragile independence likely stem more from international oversight, external powers, and India’s own strategic calculations.

So, Can You Actually Travel There?

Of course, politics is beyond the influence of ordinary people like us. Let’s get back to the practical question: are the former “Himalayan Trio” viable travel destinations?

The answer: your experience will vary dramatically depending on the color of your passport.

Nepal: Completely open. It’s visa-free for Indian citizens, offers free visa-on-arrival for Chinese citizens, and provides visas on arrival for most other nationalities. Blessed by geography, its tourism economy, centered on Mount Everest, welcomes all travelers.

Bhutan: Exclusive and controlled. Indian citizens receive special, near visa-free access. However, Bhutan has no formal diplomatic ties with China and enforces a strict “High-Value, Low-Volume” tourism policy for everyone else. This requires booking through an approved agency, paying a daily $100 “Sustainable Development Fee,” and being accompanied by a guide at all times. No independent travel.

Sikkim State: Sensitive and restricted. For Indian citizens, most areas are open. But all foreigners need a special permit. For Chinese citizens, due to historical and political sensitivities, obtaining a travel permit for Sikkim is virtually impossible. For us, it’s effectively an off-limits zone.

So, on the southern slopes of the Himalayas, the only truly open and accessible destination is Nepal.

But then again, it doesn’t strike me as the best place for a trip with a young child. Buddhist monasteries and snow-capped peaks probably can’t compete with sandy beaches and theme parks. It looks like my search for a family vacation spot will have to continue.