For most of China, the dog days of summer are just around the corner. July and August bring a special kind of misery where a quick lunch run can feel like you’re losing a layer of skin. Late last August, a colleague and I pondered why summer drags on for so long. His theory involved some myth I can’t recall, but I confidently declared, “It’s the concrete. It soaks up a ton of heat and takes a couple of months to let it all go.”

I immediately knew that sounded a bit too simple. It felt right, but it wasn’t very scientific. So, today, let’s get to the bottom of it.

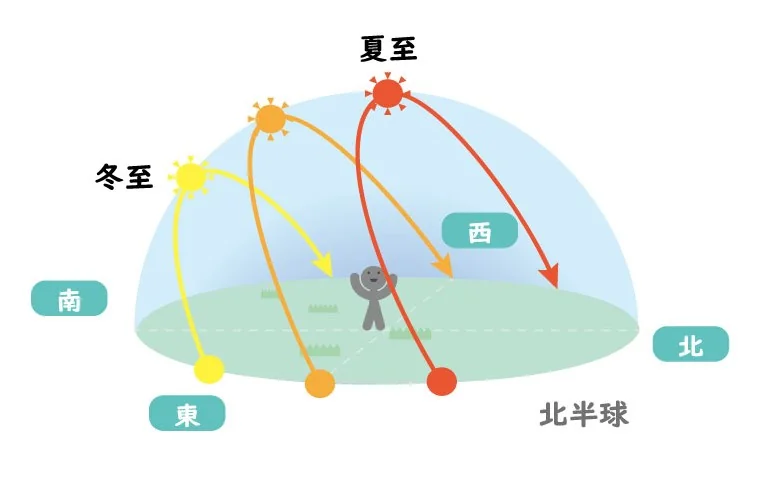

We all know the summer solstice hits around June 21st. It’s the longest day of the year in the Northern Hemisphere, when the sun is directly over the Tropic of Cancer (23.5°N latitude, near Shantou).

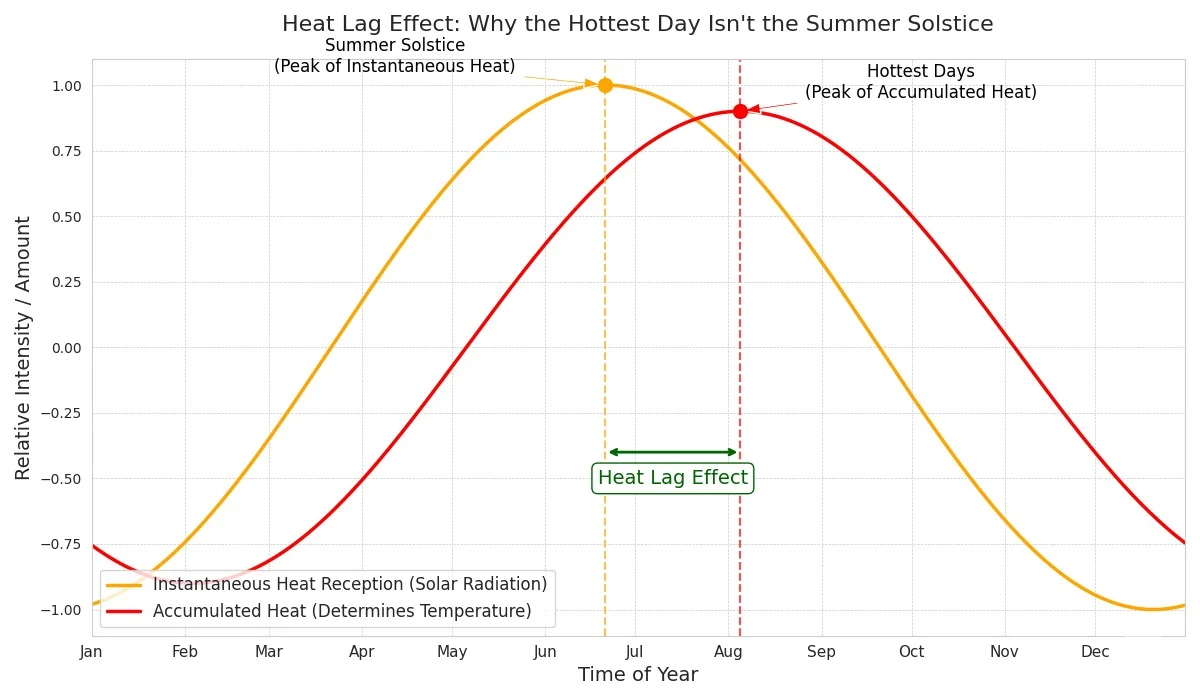

In theory, this is when we get the most solar radiation. After the solstice, the sun’s direct rays head south, and the days start getting shorter. So why are July and August even hotter?

It Starts with a Lag

Let’s begin with something we see in daily life.

Think about this: if you live in a concrete building, you’ve felt how it stays cool in June even when it’s hot outside. Opening a window is pure bliss. But come September, the crisp autumn air is a lie the moment you step inside your oven-like home.

This is especially true in South China during the “Huinantian” (Resurgence Days) in May and June. Hot, humid air condenses on the cool indoor surfaces, turning walls and floors into a dewy mess. This proves that buildings have a significant thermal lag.

My concrete theory was looking good until I remembered the 24 Solar Terms. Our ancestors knew about the “dog days” of summer long before concrete existed. This phenomenon is older than our cities; it’s baked into the Earth itself.

Earth, the Giant Thermos

To understand this, picture the Earth as a giant thermos, its surface a mix of oceans and land.

The ocean is a massive water tank with an incredible ability to store heat. It can absorb huge amounts of energy with only a slight temperature increase.

Land is more complicated. It’s a mix of water, rock, soil, and man-made structures.

Water is the key player, acting like a sponge for heat. It’s a small part of the land’s mass but holds the most heat.

Rocks and soil, on the other hand, are terrible at long-term heat storage. They have a lower specific heat capacity and are poor conductors. I once visited the Mingsha Sand Dunes in Dunhuang, where the surface sand was scorching, but just a few inches down, it was cool. The heat doesn’t travel deep.

Urban structures like concrete and asphalt are even more extreme. They have a similar heat capacity to soil but are darker, especially asphalt, which absorbs over 90% of sunlight. With no moisture, they can’t “sweat” to cool down. They bake all day and radiate heat all night, creating the urban heat island effect.

But none of this explains why temperatures keep rising after the solstice.

Here’s a better analogy: the leaky balloon. The sun pumps air into the balloon (Earth), while the Earth radiates heat back into space (the leak). On the solstice, the pumping is at its strongest. For two months after, the pumping weakens, but it’s still faster than the leak. The balloon keeps inflating.

Similarly, after the solstice, the Earth still absorbs more heat than it radiates. The planet’s heat reservoir keeps growing until, one day during the “dog days,” intake equals output. That’s the peak. After that, we finally start to cool down.

This is like “carbon peak.” It sounds bad, but it marks the point where the growth rate finally turns negative—a trend reversal.

In this process, water plays the decisive role. Water is the Earth’s most powerful “heat sponge,” capable of absorbing enormous amounts of heat with only a slight increase in its own temperature. The specific heat of water is 4-5 times that of sand and rock, meaning it can store far more heat in a much milder way.

The diurnal temperature range of a place is largely determined by the presence of water. In lush, vegetated areas with ample moisture, the temperature difference between day and night is small. In arid deserts, the difference is extreme.

To take it to an extreme, what if the Earth had no water or atmosphere? We have a perfect real-world example: the Moon. Without water as a “heat sponge” and an atmosphere as a “thermal blanket,” the heat absorbed during the day is almost entirely radiated away at night. The Moon’s surface temperature can soar to 127°C (260°F) during the day and plummet to -173°C (-280°F) at night. With such rapid heating and cooling, the phenomenon of thermal lag would cease to exist.

So, when we complain about the weather, let’s not forget the Moon. Our planet, thanks to the gentle “thermostatic suit” of water and atmosphere, has avoided becoming a hellscape of alternating extremes. They are one of the greatest miracles that allow life to thrive on Earth.

The Air Blower Barrel: The Subtropical High

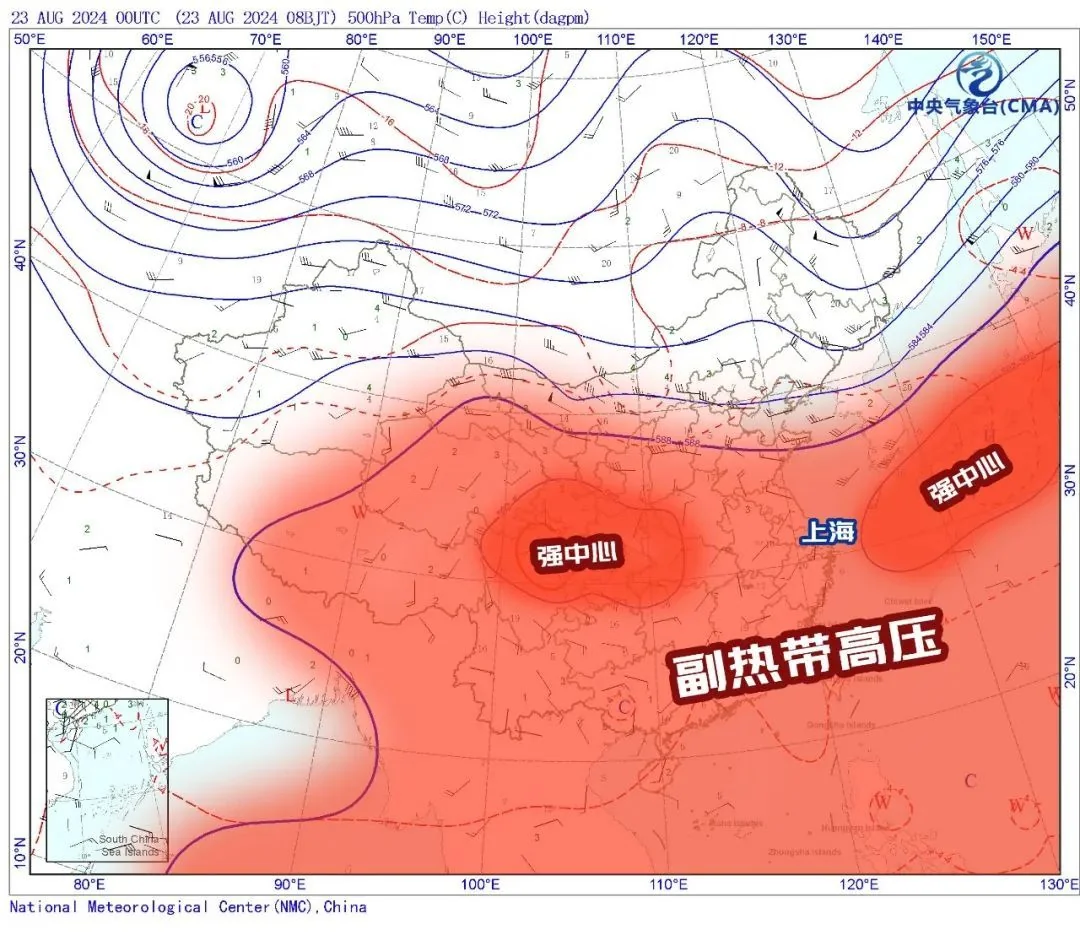

But the Earth’s own heat accumulation isn’t enough to explain the suffocating heat of the dog days. The real knockout punch comes from an old acquaintance from the weather forecast: the subtropical high. What is it, exactly? A mass of air?

Yes and no.

Picture this: in a large river, a stable vortex forms in a specific spot due to the flow patterns. The vortex itself seems permanent, but the water molecules within it are constantly being replaced. The subtropical high is a magnificent, stable air vortex in the Earth’s atmosphere.

The one that affects China the most is the Western Pacific Subtropical High. Its raw material comes from the equator. Air, heated to a scorching temperature at the equator, rises to high altitudes and then splits into two streams, one north and one south. The northward stream cools at high altitude, sinks, and traces a huge arc, landing around 30°N latitude to form this massive high-pressure system.

If it’s a current of air, why doesn’t it just dissipate?

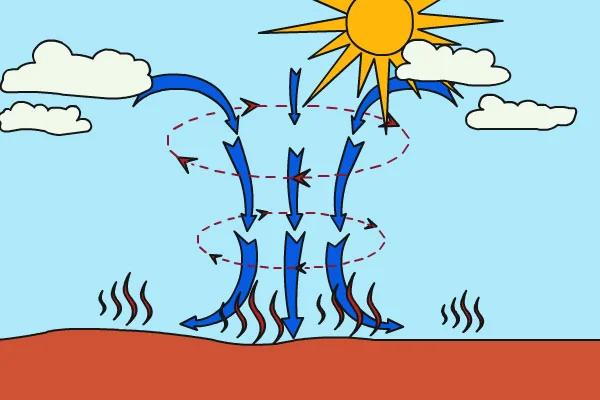

To understand its stability, we can imagine it as a bottomless, topless air blower barrel:

- The Top: Hot air from the equator rises, deflects, cools, and sinks, continuously pouring into the barrel.

- The Squeeze: The air pouring in compresses the space inside the barrel. This compression causes heating, resulting in a hot-over-cold air structure inside. This stratification prevents vertical convection. The hot air above acts like an invisible lid, letting air in but not out.

- The Walls: The trapped air naturally tries to escape horizontally. But as it blows outward, it’s deflected to the right (due to the Coriolis effect in the Northern Hemisphere). At a certain point, it bends 90 degrees, creating a clockwise “wind wall.” Other air trying to escape from the inside collides with this wall, preventing the wall from deflecting further inward. These forces merge, strengthening the wind wall and creating a balance that contains most of the air.

- The Leaks: At the bottom, however, this air barrel wall becomes less sturdy due to friction with the ground. It leaks air in various directions, forming the trade winds and westerlies.

We’ll discuss the “Coriolis effect” in detail in the next chapter; for now, just focus on the wind wall. Ever walk into a mall in the summer and feel that blast of air from an air curtain pointing straight down at the entrance? The door is open, but it’s two different worlds inside and out. That’s the blocking effect of a wind wall.

This is how this high-pressure vortex maintains its relative stability.

The subtropical high, this “air blower barrel,” is a living thing. Its shape and position are constantly changing. When it expands northward and envelops your city, the weather forecast will say the area is under its “control,” a very fitting term.

Imagine the scene from the movie Independence Day where the alien mothership slowly emerges from the clouds and hovers over the city—the subtropical high brings that same sense of oppression.

It makes you feel scorching hot in two main ways:

- Sinking Air, Cloudless Skies: Inside the high, the air sinks. This presses the hot surface air down, preventing it from rising to meet the cold air above, which suppresses cloud formation. The result is a clear, sunny sky, allowing the sun to launch a direct physical attack on you.

- Transporting Moisture, Muggy Heat: The high often packages and delivers the hot, humid air from over the tropical oceans. High humidity prevents your sweat from evaporating, effectively crippling your body’s cooling system. This is a magic attack.

It’s crucial to note the difference between how the body feels heat from ground radiation versus heat from water evaporation. The former is “sensible heat,” the latter is “latent heat.”

The ground radiates heat via infrared radiation, transferring some of its stored energy to your house, your body, and the surrounding air. The ground cools down, but for you, it’s a heating process—that roasting feeling you get on a summer evening.

When water evaporates, it absorbs a large amount of “sensible heat” and converts it into “latent heat” stored in the water vapor molecules. This heat, which was on the ground or on your body, suddenly seems to vanish into thin air. This is true cooling. Of course, the heat hasn’t disappeared; it’s just been carried away to the heavens by the water vapor.

So, in July and August, you can experience two very different kinds of summer heat. When you’re away from the subtropical high and only dealing with ground heat, it’s a relatively dry heat. You can ride a bike in the hot wind and barely break a sweat. When the subtropical high hits, it’s the kind of heat that makes your clothes stick to you, so muggy you don’t even want to speak.

These are two different summers. One is the summer of a vibrant, energetic high-school athlete; the other is the summer of a sweaty, stressed-out recent grad hunting for a job.

The Coriolis Effect

Now let’s dive into the Coriolis effect, also known as the geostrophic deflection force, and see where the “barrel wall” comes from.

This force is fascinating. It’s not a real push or pull but an inertial phenomenon.

Imagine a cannonball fired from the equator, aimed straight for the North Pole. There are two ways to understand the Coriolis effect.

From the perspective of an observer on the ground:

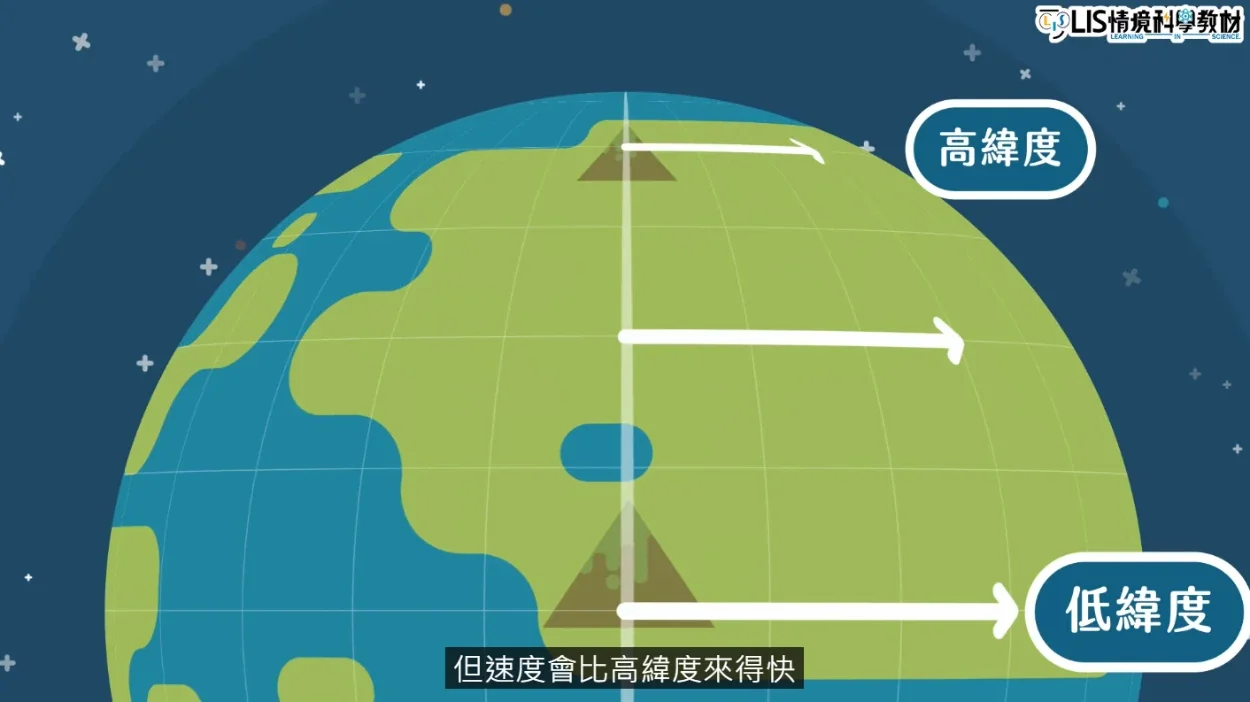

When the cannonball launches from the equator, in addition to its northward velocity, it carries a huge west-to-east inertial velocity from the Earth’s rotation (about 1670 km/h or 1040 mph). As it travels north, the latitude increases, the circumference of the latitude line decreases, and the rotational speed of the ground below it slows down. But the cannonball, due to inertia, maintains its high equatorial speed. Consequently, it “outruns” the ground beneath it, causing its path to curve eastward. For a northbound cannonball, this is a deflection to the right.

Conversely, if fired from the North Pole towards the equator, the cannonball’s initial east-west velocity is zero. As it flies towards the equator, the ground beneath it is moving eastward at an increasing speed. The cannonball “can’t keep up” and lags behind, deflecting westward. For a southbound cannonball, this is also a deflection to the right.

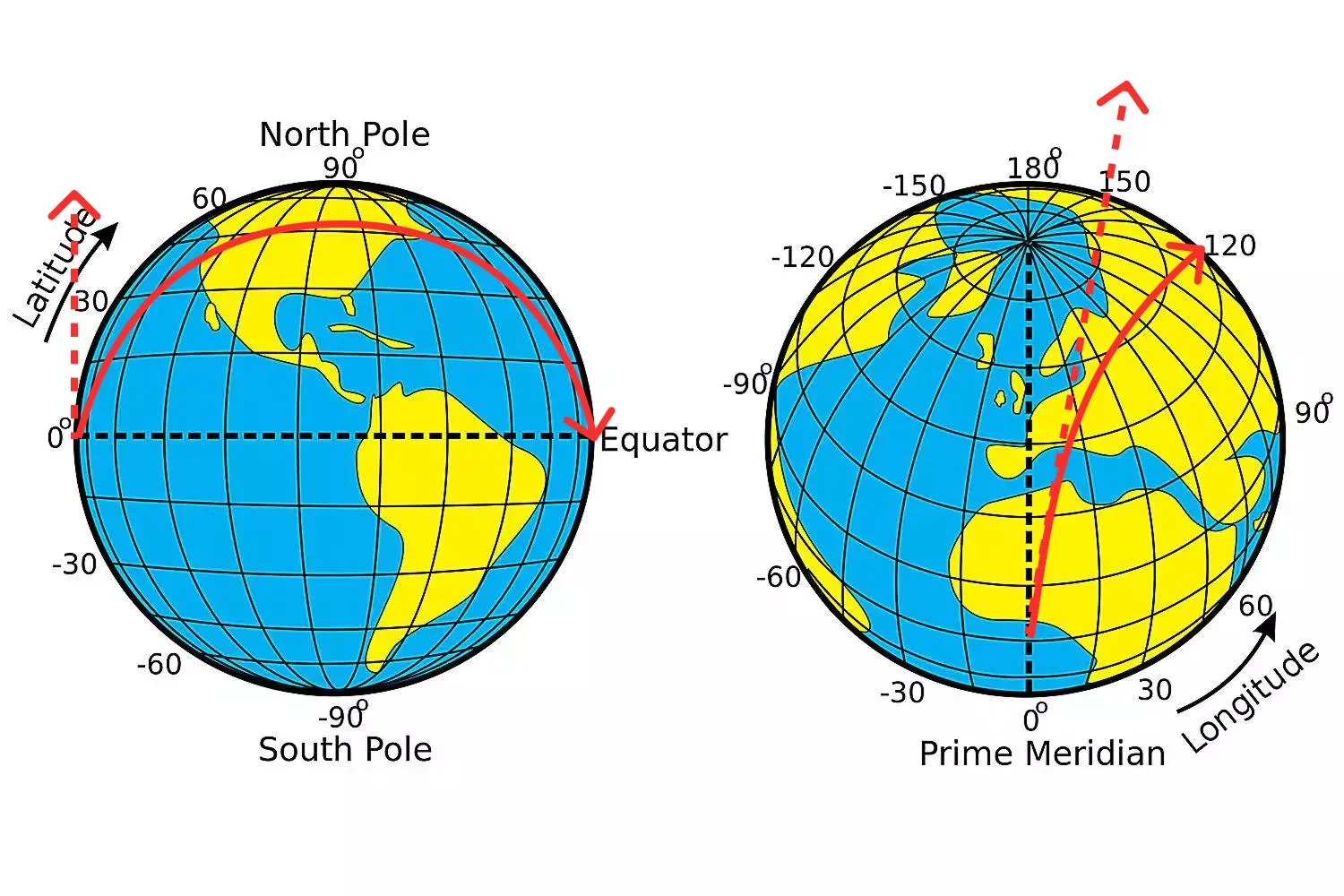

From a God’s-eye view:

Watching from space, you’d see the rotating Earth move the cannonball to the side. You’d notice that when the cannonball launches from the equator, its initial direction isn’t straight up but diagonally up and towards you. Ignoring gravity, it would travel in a straight line in space. But gravity pulls on it, essentially “taping” this straight line onto the Earth’s surface, making it follow a “straight line on a curved surface.” This is also known as a great-circle route, the shortest path on a sphere. You can see this by stretching a string on a globe. The cannonball would travel northeast, reaching a high latitude where its direction is due east, then curve southeast, its latitude decreasing until it returns to the equator.

It was aimed north, but it passes the North Pole to the northeast. To someone on the ground, doesn’t that look like a rightward deflection?

So, the Coriolis effect isn’t a force; it’s an illusion. We are spinning but often forget we are. We only realize something is amiss when things don’t travel in the straight lines we expect.

The famous Foucault pendulum experiment in science history used this principle to prove the Earth’s rotation. It’s also why atmospheric phenomena are always spinning.

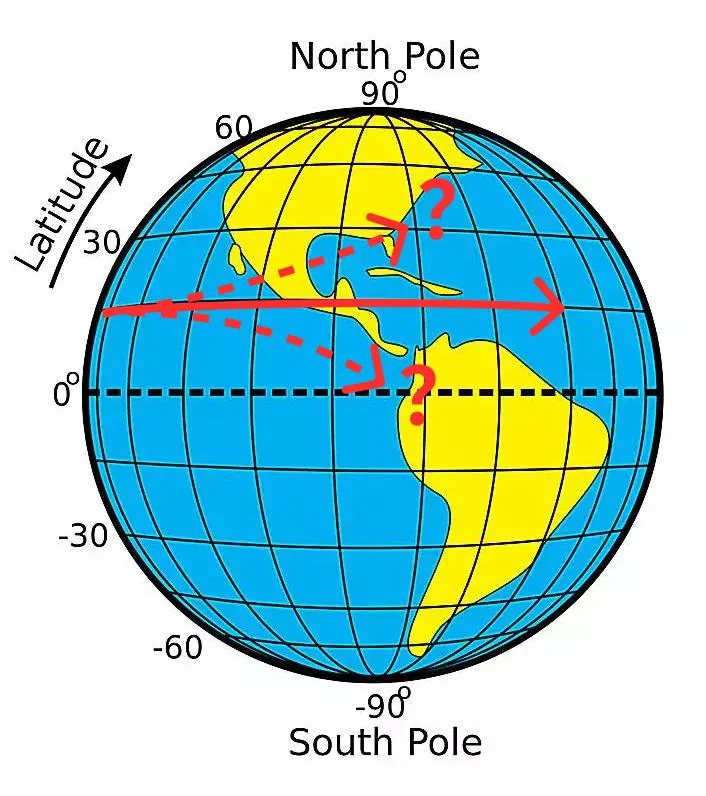

But wait! Sharp-eyed friends might spot another issue. What if the cannonball is fired horizontally at a mid-latitude, with no initial north-south velocity? Why does it still deflect? The “different speeds at different latitudes” explanation doesn’t seem to cover this.

Congratulations, you’ve entered the deep end of the Coriolis effect. You’ve discovered an important fact: physically, the Coriolis effect isn’t driven by a single principle. The north-south deflection is mainly due to the conservation of angular momentum, but the east-west deflection is primarily caused by the balance of centripetal force.

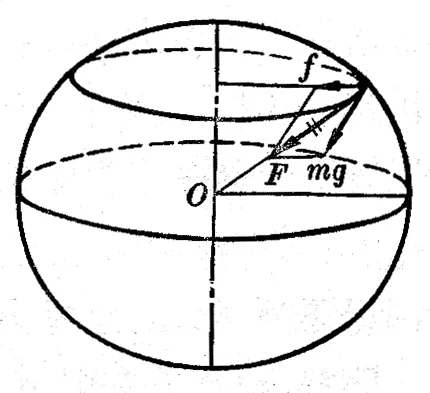

First, let’s reiterate an important concept: Gravitational Force ≠ Gravity.

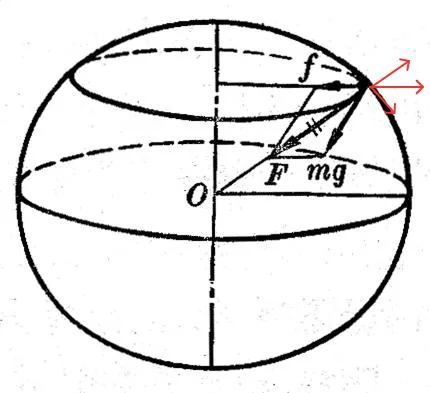

Gravitational force (F) is due to the Earth’s mass; it exists whether the Earth spins or not and points towards the Earth’s center. Centripetal force (f) only exists with rotation; the faster the spin, the more centripetal force is needed. It points perpendicularly towards the Earth’s axis of rotation. These two forces have different directions. The part of the gravitational force that remains after accounting for the centripetal force is the gravity (mg) you feel. Of course, since gravitational force is very large and the required centripetal force is very small in comparison, the direction and magnitude of gravity are very close to that of the gravitational force.

Note that gravitational force is constant, while centripetal force isn’t a force an object actually receives; it describes the force required for an object to maintain its orbit at a certain speed.

So, for a cannonball at rest, the gravitational force is constant. The component of gravity in the direction of the centripetal force (let’s call it the centripetal component) provides just enough force to keep it stationary.

If fired eastward, the gravitational force is unchanged, but its orbital speed is now its own speed plus the Earth’s rotational speed. It’s moving faster than its latitude. The centripetal component of gravity can’t provide enough force to hold it. It has a tendency to fly off into space, opposite to the direction of the centripetal force. This outward tendency can be split into two components: one perpendicular to the surface and one along it. The perpendicular one doesn’t affect deflection but creates the interesting Eötvös effect (which we won’t get into, or we’ll never finish). We’re interested in the motion along the surface. The cannonball will move towards a lower latitude where more centripetal force can be provided. So, it moves south, deflecting to the right.

If fired westward, the same logic applies. Its combined speed is slower than its latitude. The centripetal component is now excessive, creating a tendency to pull it towards the axis of rotation. Along the surface, this manifests as a northward movement, which is also a rightward deflection.

Once it deviates from a pure east-west path, the angular momentum factor starts to play a role in the north-south direction, ensuring the cannonball continues to deflect.

Studying this leaves a strange feeling. How can this be? Can multiple physical laws combine to form a new one? Is this some kind of nesting doll? But mathematicians see it differently. The formula they derived for the Coriolis force is:

$$ {\displaystyle {\vec {F_{c}}}=-2m({\vec {\omega }}\times {\vec {v}})} $$

I won’t explain it in detail, but this formula covers both east-west and north-south cases simultaneously. Oh, so two different things in physics are the same thing in math… Sorry, my mistake.

Let’s stop here with the Coriolis effect. We have enough information to explain the thermal lag. In short, the existence of the Coriolis effect allows the subtropical high to maintain its “barrel wall,” trapping the high-pressure air inside and creating this unique atmospheric phenomenon.

A quick reminder: in everyday life, the Coriolis effect is not very noticeable. The direction of the vortex in your toilet or sink drain is mainly determined by the shape of the basin and the initial disturbance of the water, not this force.

The Conspiracy of the Thermos and the Air Blower

Alright, back to the main topic. We can now summarize. After the summer solstice, two factors conspire to keep the weather getting hotter:

- The Thermos: The Earth’s continued accumulation of heat.

- The Air Blower: The external heat delivered by the subtropical high.

Which factor has a greater impact? That’s like asking in a gas explosion whether the gas or the spark is more to blame.

The heat stored by the land, especially by the “heat sponge” of water, is the gas filling the air. It determines the baseline and duration of the heat. On one hand, it stores a massive amount of heat in early summer, preventing the surface temperature from rising too quickly, which is why the solstice isn’t the hottest day. On the other hand, the heat it has accumulated peaks in July and August, finally causing a significant rise in near-surface temperatures, creating a kind of “stone pot bibimbap” baking heat.

At this point, the intense heat is like gas filling the air, just waiting for a spark.

And the humid, scorching blast from the subtropical high is that fatal spark, making you feel like you’re about to explode. This is the inescapable reality of the dog days of summer.

Well, after all that, I know you don’t feel any cooler. Neither do I. Even the toothpaste in my bathroom is warm.

Finally, on the topic of summer, you might also be interested in this: Why Can the Summer Sun Shine on a North-Facing Wall?